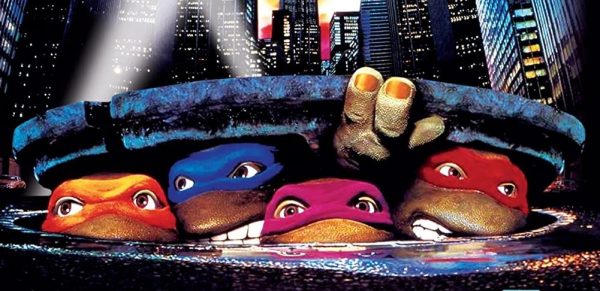

Luke Owen sits down with Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles director Steve Barron, producer Tom Gray, Donatello suit actor Leif Tilden and co-creator Kevin Eastman to find out how the movie got made…

In 1984, Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird self-published a comic book that would grow into a cultural phenomenon that lasted longer than anyone could have expected. The first issue of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles sold out everywhere with several stores demanding more orders, and before they knew it Eastman and Laird were sat on one of the most successful comic book properties of the 1980s. “We always wanted to be Jack Kirby, and suddenly we were” Eastman jokes. “We weren’t as big or as talented as Jack Kirby though”.

Eastman and Laird were joined by Mark Freedman as a business partner, who began to strike deals with various companies to expand the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles brand. He signed a deal with Playmates to release a line of action figures, and this was supported by a Saturday morning cartoon series that introduced more characters that could be sold as toys. The ratings for the show were huge, and the action figure line comfortably competed against former giants like He-Man and the Masters of the Universe, and current fads The Transformers and The Real Ghostbusters. It didn’t take long before Hollywood came knocking at the door.

Back in the late 1980s however, the idea of making a movie based on a comic book was not as a guaranteed success. Superman: The Motion Picture, released in 1978, was a financial and critical giant for Warner Bros., but its subsequent sequels and spin-offs couldn’t capture the original magic. Superman III, Supergirl and Superman IV: The Quest For Peace – though not released by Warner Bros. – were box office bombs and critical flops, and it looked as though comic books on the big screen was a sure-fire failure. This all changed in 1989 with the release of Tim Burton’s Batman starring Michael Keaton as The Dark Knight and Jack Nicholson as his arch-nemesis The Joker. The film had a modest budget of $35 million, but its clever marketing campaign and unanimous praising from fans and critics alike meant Batman was one of the highest grossing domestic movies of the year with $251 million. Suddenly it looked like the comic book boom was back.

One company that was interested in getting involved was Hong Kong based production team Golden Harvest, best known for kick-starting the careers of Bruce Lee with Enter the Dragon and Jackie Chan with The Big Brawl. However it wasn’t an instant attraction. “When I was living in London in the ‘70s working for Paramount, I got addicted to Are You Being Served? on British television, which is one of my favourite shows,” says Golden Harvest producer Tom Gray. “So when I came back to the United States, I wanted to somewhat draft an American version of it. I went out and hired Bobby Herbeck and we started writing a script about Are You Being Served? American style, and along the way he kept telling me about how he had a comic book from Gary Proper, who was Gallagher’s road manager, and he was reading these Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles comic books on the road. He said I should take a look. And I said, ‘that’s the stupidest thing I ever heard, I don’t want to take a look at this’. I said, ‘if I send this to Hong Kong I’m in big trouble’.”

For the next few months, Gray was propositioned further with the idea of bringing the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles to the big screen and he kept turning it down. However during a meeting at a creole bar with Herbeck and producing partner Kim Dawson in West Hollywood, he had a change of heart. “I was sliding out of the booth and I had an epiphany,” he recalls. “I said, ‘wait a minute – this is nothing more than four Chinese stunt men from our studio in Hong Kong in rubber suits. We can knock this off in Hong Kong for a couple of million bucks and sell it to the Japanese, and away we go’.”

After securing the movie rights from Eastman and Laird, Tom Gray hired Herbeck, who had previously worked on shows like The Jeffersons, Small Wonder and Diff’rent Strokes, to start writing a first draft as he was the real driving force behind getting the deal. Part of the deal struck with Eastman and Laird was that they would have final sign off on the story but not the script itself, which meant Herbeck had to convince the duo he was the right man for the job. Herbeck presented several story ideas to Eastman and Laird which were all rejected, but the central idea of the Turtles battling Shredder and his Foot Clan army, who are recruiting runaway teenagers off the street, won them over. Sadly, his scripts didn’t match up to their expectations. “He presented some ideas that we weren’t happy with, and we seriously reconsidered not doing the first movie because we felt that someone who worked on The Jeffersons wasn’t the right writer,” Eastman recalls of his meetings with Herbeck. “That’s when we had some conference calls with Tom Gray and said we weren’t happy with Bobby. We like him as a person and he’s talented and we appreciated all his efforts, but he’s not right for the movie.”

Thankfully for Tom Gray and Golden Harvest, Eastman and Laird’s trepidation with the live action adaptation was short lived when they hired director Steve Barron, who in turn brought in screenwriter Todd Langen. “When Steven came in, he’d gone through the black and white comic books and post-marked scenes that he thought would work well as a whole movie and he brought in Tom Langen to do the writing,” Eastman adds. “And his experience from The Wonder Years brought some great emotion to the roles for these guys to bring to life.”

Barron had made a name for himself as a director during the rise of MTV, working with on music videos for artists like A-Ha (“Take on Me”) and Michael Jackson (“Beat It”), and it was this style that Gray wanted to bring to Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. “That was all the rage at that point,” Gray says of MTV. “It was at this point we stumbled upon Steve Barron. I thought that’s the guy who can make this stuff come alive.” Barron’s hiring for Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles was very much by coincidence, as he was working on the TV show Jim Henson’s The Storyteller which had Anthony Minghella working on it as a writer. Mangella had been contacted by Golden Harvest for advice on the script, and it was here that he passed the comic to Barron. “I loved it because I had not seen or heard of it before, and it was an extraordinary idea, a very different idea, something that I had never seen before in a movie which was a big criteria back in the 1980s,” Barron recalls. “Doing music videos, the first thing on the list is ‘has this been done before?’ If it hasn’t, I want to do it.”

For Eastman, the hiring of Steve Barron was perfect as not only were all of his ideas coming straight from the pages of the harder comic book, but he was also able to adapt the softer attitude from the popular cartoon series. “We had several different universes at the time,” Eastman says. “We had the black and white Turtles comics which had a bit more violence which were written for an older audience – in fact Peter and I wrote them for ourselves – but the animated series was being geared towards a younger audience.”

Being designed for a younger audience, several aspects of the series were changed from the rather violent source material. The Turtles were given unique bandana colours to help children identify them – which also helped with the toy line – and the Foot Soldiers were changed from ninjas to a robot army so the Turtles could dispatch of them without killing anyone. “What Steve did was almost create a new universe which was the middle ground between the comics and TV series, which I thought was done and written so well that it ended up being for all ages,” Eastman says. “There were things in it that were there for an older audience that the younger audience would not understand, but it still had the pizza and jokes which was there for the younger audience.” Barron adds: “The darkness and the tone was something I wanted to keep. In the end, you direct most things for yourself and your own tastes. The tone of it was similar to The Storyteller, they were darker myths but still for families.” Barron had several discussions from a worried production company in Hong Kong about his decision to focus more on the dark aspects of the comic rather than the light tone of the cartoon series, but the director stuck to his guns. “A) it was too late, and B) I didn’t agree,” he jokes. “You couldn’t underestimate what kids can take – as it where – and how they’ll read things. I didn’t think that it was too dark. It was way different to the cartoon, but I felt that kids would just find it more real. I didn’t think that was a bad thing with what kids were watching.” Leif Tilden, who would be in the suit of Donatello in the movie, was a huge fan of the comic books and agrees Barron’s approach wasn’t ‘too dark’. “My first impression [of the script] was that it was a lot less dark than the original [comic].” he says. “I still believe a dark version would be amazing. An origin film before they had different color bandanas. Reckless teens.”

However the tone of the movie was the least of Tom Gray’s concerns. When Barron came on board he suggested bringing in Jim Henson and his Creature Workshop to create the suits for the Turtles, but this came with a high price tag. “The budget went from fifty cents to six, seven, eight million,” he says. “Which I was getting terrified about because no one was picking the movie up here in the studios.”

Gray had approached every studio in Hollywood to offer them distribution rights for Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, but no one was interested. Although Batman was a hot topic in the industry, previous comic book movie failures had warned studios off the idea of taking on the genre. “I was making the rounds in Hollywood, everyone was telling me ‘no’ because they didn’t want to be the next Howard the Duck,” Gray recalls. “Everybody thought that if the mighty George Lucas can’t make it work with a comic book, how can I who is a nobody.”

Released a couple of years prior and based on the cult favourite Marvel comic of the same name, Howard the Duck was George Lucas’ first project following his mega-successful Star Wars trilogy. The film boasted state of the art puppetry effects and an impressive budget of $37 million, but only grossed $16 million domestically among a wave of bad reviews. The movie did little for Lucas’ own personal financial affairs, and the director was forced to sell off his newly formed computer animation department to Apple CEO Steve Jobs, which eventually became Pixar Studios.

With Howard the Duck still in the back of studio executive’s minds, getting Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles mounted was becoming very difficult. “I would tell them that Howard the Duck didn’t have Henson’s people behind them, and Howard the Duck was not the merchandising phenomenon that the Turtles had become. It wasn’t a syndicated kid’s show on television,” Gray said. “If you put this in front of kids and we execute it well, there is every reason it will connect and everyone will make money. The highest names in the industry turned me down. Not once, not twice, but three times.” Eastman adds: “He would sit down with people in Hollywood and start talking to them about the Turtles and the comics and they would look at him like he had lobsters crawling out of his ears. They all said, ‘you’ve got to be kidding me – are you serious?’ To his credit, his faith and epic ability to sell it as a package and bring it together and make it happen, even having the savvy to bring in someone like Steve Barron and his vision, and Jim Henson and his Creature Shop to bring it to life. He worked miracles.”

One studio who eventually agreed to the project was 20th Century Fox, who were in serious negotiations to put $6 million into the production budget along with the money Golden Harvest had already invested on pre-production. But as Henson and his team began building the suits ready to be shipped over from London to Carolina, Fox had a change of management and decided not to move forward with the deal. “It was one of those eleventh hour calls to my crew in Wilmington, Carolina,” Gray says. “I said to my crew, ‘guys if we don’t get the money, be prepared to shut it down. You’ll have to stop Henson flying from Heathrow and coming in. Because we’re in deep shit’.”

In the last few hours before Henson was to fly out to Carolina and begin production, Gray received a call from New Line Cinemas who offered him a deal. “New Line Cinema came up to me and said, ‘we know you struck out everywhere in town, we know you don’t have a deal, we’re you’re last hope’,” he recalls. “I said, ‘yeah, I need six million’. And they said, ‘we’ll give you two’. And I said, ‘I can’t make the film for two million’.” With no other options, Gray waited until it was 6am in Hong Kong to call Golden Harvest founder Raymond Chow to tell him the bad news. “I said, ‘we don’t have the money’,” he says of the phone call. “He said, ‘what are we going to do?’ and I said, ‘okay you’ve got two choices. You can give me the money to make the film, or we’re going to get sued because we’ve got pay or play with Henson which will cost us four million.’ He asked what I thought, and I said, ‘I only will promise you one thing: you will get your money back. I’m not saying it will work, I believe that if we execute this the way it’s going we’ll get our money back’. And he tells me he’ll get the money. I call Carolina and I told my producer and told him to get on the phone to London and tell them to let the boats go because we’re going. That’s how close it got to being shut down.”

Production took place in Wilmington, North Carolina in very testing circumstances. “It was extremely difficult to shoot because the technology in those days was new technology,” Gray recalls. “We couldn’t keep these guys in rubber suits in North Carolina because it’s like 95 degrees and 98% humidity. They were passing out and there was a lot of panic.” However it wasn’t just the humidity causing issues. “The other problem was they had to be able to use servo motors and radio waves because we could not show high kicking kung fu if they were hot-wired,” Gray adds. “When we started shooting, we had so many problems because we were shooting next to an airport. Every time a plane would come in, all the Turtles would start to react differently because the radio waves. So we had to go to military frequency.” Eastman adds: “The first thing I thought about watching Steve Barron as director – standing there surrounded by a hundred different people from lighting, actors, extras – the first thing I thought was, ‘it’s amazing any film comes out good, ever.’

Tilden recalls that the atmosphere on set was “electric”, and adds the suits weren’t as bad once you were inside them. “The suits were crafted on our body casts,” he says. “We were very connected to ‘the skin’ of the Turtles. They were not cumbersome but extremely hot. The shell housed the computer which moved the facial expressions in the head which a puppeteer moved from a remote control. It wasn’t that tough except for the heat.” He does however add that the shoot improved significantly very early on. “The first day doing thirty-six takes for the opening sequence was like being in Vietnam trying to survive the heat because we were in costume the entire time without a break,” he recalls. “Everyone realised after that we needed to come up for air.”

With the movie finished, Golden Harvest and New Line Cinemas took Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles to Show West, a convention held in Las Vegas where all the major studios show their films. “We went up against The Hunt for Red October,” Gray recalls. “Everybody that had gone out to see Hunt for Red October didn’t go, they came to see Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. It was the first time that we knew we had a smash. We had filled up the auditorium with kids, and we had all these old, jaded distributors come in from all over America – and the kids were going nuts. It was pandemonium.” Eastman adds: “When we finally sat down in the theatre to watch it with all the sound, music and editing and how it all came together was just mind-blowing. It felt like our comic books had come to life faithfully and truthfully. It was riveting.” Leif Tilden adds, “I liked it for the most part. I thought the production value was sketchy at times because I thought it should have been all practical locations. I wasn’t impressed with the sets except the sewer.”

Released on March 30th 1990, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles knocked Pretty Woman from the top of the box office charts but received very mixed reviews from critics. While Dave Kehr of Chicago Tribune noted, “The results are lively and funny enough to keep adults enthralled as well as kids,” and Desson Thomas of Washington Post wrote, “amid the kiddie pollution available on Saturday morning TV, the Turtles rank slightly better than the rest,” many critics took issue with its tone. Jay Boyar of Orlando Sentinel said, “What troubles me about Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles is that it’s basically an exploitation movie aimed at young children,” and Janet Maslin of New York Times called it a, “a contentious, unsightly hybrid of martial-arts exploitation film and live-action cartoon.” Among the bad reviews, with Entertainment Weekly calling it a “dismal, tedious affair,” Gray took issue with Siskel and Ebert’s negative views. “I happened to be scouting locations for another movie and I saw them in this café,” he jokingly recalls. “I was so pissed that Ebert had crapped all over Ninja Turtles and called it terrible and a waste of celluloid and all that stuff. I went over to him and said, ‘Mr. Ebert, I respect you as a film critic but you have no sense how this business works’. And he looked up at me like, ‘who the fuck are you?’ So I said, ‘I made Ninja Turtles’. And he says, ‘you’ve ruined my dinner’. We had this little argument but it was all in fun. You can’t make these movies with the critics in mind.”

One person who was happy with the film was Kevin Eastman. “That first movie will always be my favourite version of all things entertainment for the Turtles,” he says. “A few years ago at Tribeca, they did a screening of the movie for fans. I was hanging out with Steve Baron and we introduced the film and then I watched it, and it was the first time I’d seen it in fifteen years. And I sat there and thought, ‘this held up pretty good in the end’. It was so much better than I ever could have imagined. Thanks to Steve Barron and Jim Henson who made that all happen – and the poor guys who had to wear the eighty-pound suits.”

Though it may have divided critics, there was no arguing the movie’s success at the box office. “Hunt for Red October opened a week before us,” Gray recalls [Note: it actually opened five weeks before]. “And I ran into the guy from Paramount who turned me down several times at a basketball game and I said, ‘congratulations – it looks like it opened well.’ It opened with $18 million which was a record for non-holiday. And he said, ‘yeah we’re going to own this spring.’ And I just smiled. I knew the Turtles were going to open big. We opened to $25 million, so we smashed every record.”

New Line Cinema decided to open Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles a week before the school holidays, which meant on its second week it got kids all over again, dropping just 25% to $18 million. “Which is unprecedented in this business,” Gray notes. “Everybody who passed on the movie called me up on the Monday and said, ‘God – how did we miss this?’ And I simply said, ‘you didn’t believe in it’. So they said, ‘okay – we believe in its sequel.’”

My thanks to Tom Gray, Leif Tilden and Kevin Eastman for their time contributing to this article. Steve Barron’s quotes are taken from this interview I conducted with him.

Luke Owen