Sarah Myles has a close encounter with the shark movie genre…

Movie trends ebb and flow, with thematically similar stories washing through our cinemas at regular intervals. War films, biopics, westerns, slasher movies, ghost stories – each has its season, and they return again and again in cyclical fashion. One trend that seems to be a constant, however, is the shark movie. Indeed, hardly a year goes by without some filmmaker or other telling a tale featuring these mythic marine villains.

It makes sense, because sharks make for excellent villains. Their almost prehistoric nature taps into our most primal fears, and these are then enhanced by the fact that these creatures lurk silently in the depths that represent a territory other than our own. Any encounter with a shark means that we, as humans, are literally and figuratively out of our depth. The water is their space, and we are the invaders. The epic conflict is swirled right in.

Then there’s the behaviour and appearance of the shark itself – their dead, emotionless eyes, and their numerous rows of pointy teeth; the supposed unpredictability (from a layperson’s perspective, at least) of their behaviour, and their solitary reputation (although – fun fact – a group of sharks is often called a ‘shiver’). The movie shark is, to all intents and purposes, an unknowable killing machine that will never respond to reason, or empathy. It is, in many ways, the marine-based equivalent of John Carpenter’s Michael Myers – relentless, determined, dispassionate, and cold-blooded. It’s the T-800 of the high seas.

That’s why 1975’s Jaws is such a lynchpin of the shark movie genre. It taps into all those elements of the creature, and pits it against three men in a boat who are trying to defend the population and economy of a town. All of that is set to an iconic theme tune which perfectly captures everything about the shark that gives us the major creeps. But, not all shark movies are such classic ‘Hero defends a town’ tales. The beauty of the shark as a film character is that it can be applied to any number of scenarios, across any kind of genre – action, drama, thriller, horror, and even children’s movies. Just as it does in the ocean, the shark survives in cinemas because it is resourceful and cunning.

August 2018 saw the arrival of Jon Turteltaub’s The Meg. This is an action-horror-sci-fi blend based on the novel by Steve Alten – and stars Jason Statham as Jonas Taylor. Jonas claims to have once been attacked by a 70-foot shark (akin to a Megalodon), and he is forced to confront his residual fears when he is called upon to save the crew of a stricken submersible. As a viewing experience, this premise cranks up our inherent fear of sharks by making the villain a really, really big shark – and that has always been an effective ploy.

But, the very best shark movies are those that take the concept of human-versus-shark-in-an-inhospitable-environment and apply it to even bigger narrative themes. There are, in reality, countless shark movies – ranging from 2009’s Mega Shark Versus Giant Octopus and 2010’s Mega Shark Versus Crocosaurus, to 2011’s Super Shark and 2013’s Ghost Shark – but it actually takes more than just a toothy predator to make a shark movie that stands out from the shiver.

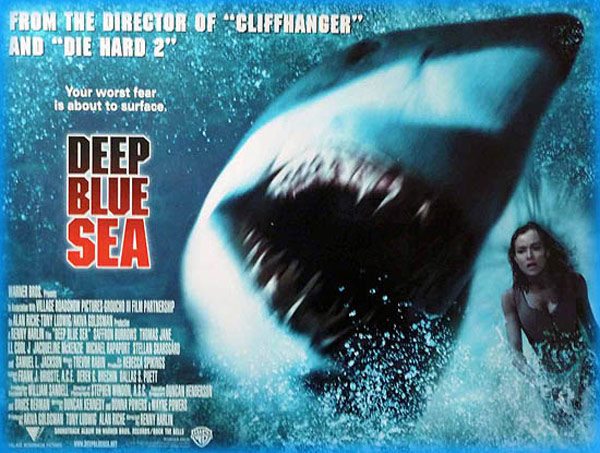

Deep Blue Sea (1999)

Directed by Renny Harlin – from a script by Duncan Kennedy, Donna Powers, and Wayne Powers – Deep Blue Sea stars Saffron Burrows, Thomas Jane, Samuel L Jackson, Michael Rappaport, LL Cool J, Aida Turturro, and Stellan Skarsgaard. It is set in an underwater facility where a group of scientists are researching captive Mako sharks in an attempt to develop a cure for Alzheimer’s patients. When one of the sharks manages to escape, though, investors in the project send a representative – Russell Franklin (Jackson) – to investigate on their behalf.

The project doctors experience a breakthrough while testing the brain tissue of the largest shark, but it then attacks the facility, causing extensive death and damage. The remaining doctor – Dr Susan McAlester (Burrows) – reveals that the sharks have been genetically engineered to increase the size of their brains, so more tissue can be harvested. This has clearly resulted in them becoming smarter, and more lethal. With their means of escape damaged and limited, the survivors fight for their lives, while trying to stop the rest of the sharks escaping into the wild.

This story takes the shark movie concept and layers it with three ethical themes. Firstly, there is the issue of marine animals being held in captivity. These autonomous living creatures are imprisoned, simply because humans have decided they want to use them for research. Secondly, there is the issue of the ego and morality of the human race – technology having allowed for the diagnosis and understanding of a degenerative brain disease, and technology providing the means to painfully exploit a different species in the pursuit of a cure. Thirdly, there is the issue of genetic engineering – whether interfering with the genes of any living creature is ever warranted, or advisable.

This narrative design – wrapping important ethical debates in the high sheen of an all-out action movie – proves to be highly effective, and the result is one of the best post-Jaws shark movies ever made. This success, of course, is aided by the performance of Academy Award nominee Samuel L. Jackson – which comes to an abrupt end during his particularly stirring monologue. This moment provides the best shark-kill of the movie.

The Shallows (2016)

Buried inside this survival-thriller shark movie – written by Anthony Jaswinski and directed by Jaume Collet-Serra – is a tale as old as time: A person in emotional distress heads out to find some peace of mind, and finds themselves instead. It is the fact that she is faced with a hungry and relentless shark that prompts the epiphany here, though – making this an excellent example of the use of the concept to explore bigger themes.

Nancy (Blake Lively) is grieving for her recently deceased mother and, in an attempt to recover from that loss, feel close to her, and take stock of her own life, she travels to the same secluded Mexican beach that her mother visited while pregnant with Nancy. Here, Nancy spends time surfing, and communicates with her sister and father back home by video-call. We learn that the loss of her mother has made Nancy question her choice to study medicine. There are two men also surfing in the cove, but it is after they leave that Nancy notices a whale carcass nearby, and is attacked by a large shark.

She suffers a significant shark bite to her thigh, and initially scrambles onto a rock out in the water. Being – somewhat conveniently – a medical student, Nancy is able to treat her wound before being stranded on the rock overnight. A man arrives on the beach to steal her unattended belongings, but is killed by the shark when he enters the surf. The two other surfers return, but are also killed by the shark. Nancy is able to fish the go-pro camera of one of the dead surfers from the water, and uses it to send messages back home.

Realising that the rock on which she is stranded will soon be swallowed by the rising tide, Nancy studies the shark’s movements and picks the ideal time to relocate to a nearby buoy – on which she (also conveniently) finds a flare gun. Her attempts to signal a distant ship prove fruitless, and when she tries to shoot the shark, she just sets fire to oil leaking from the whale carcass. The shark attacks the buoy, and rips its anchor chains from the ocean floor – sending Nancy into a dive downwards. She is able to shift direction quickly, though, and the shark is impaled. Nancy is rescued and is seen, much later and now a fully qualified doctor, surfing with her sister.

The film begins with Nancy experiencing a crisis of confidence. She is at a psychological cross-roads, and is trying to determine whether or not she is on the right path – all of which is an emotional maelstrom caused by the death of her mother. She seeks time and space to make sense of the noise in her head – to achieve some kind of clarity of purpose. In essence, the shark is representative of all of those challenging elements in her life that have brought her to the beach. She is beginning to feel some spiritual peace by shedding all of her daily obligations and focusing on the action of surfing the waves – connecting with the natural energy of the ocean, and embracing its constant rhythm. But, she is unexpectedly and literally derailed from that, when the shark strikes her and knocks her from her board.

She is plunged deep into churning, inhospitable water – where she is at real risk of drowning – and is seriously injured by that which has knocked her off course. If the water is analogous to emotion, and the shark represents the chaos and obstacles in her life, then the rock and the buoy are the temporary moments of clear-headedness she experiences while trying to figure out how to reach her final goal: the beach – analogous to her confidence in life, on which she has lost her grip.

That means that the epilogue – in which Nancy is happily healed, on track, and surfing once more – takes on greater meaning. The water is still representative of emotion, but the fact that Nancy surfs out into it without hesitation – despite her previous, terrifying experience of it – illustrates that Nancy is once again willing to tackle her feelings head-on, having been empowered by her survival of the tumult of the past.

47 Meters Down (2017)

Two sisters – Lisa (Mandy Moore) and Kate (Claire Holt) – are vacationing in Mexico while Lisa recovers from the end of her long-term relationship. We learn that Lisa’s boyfriend rejected her because she was “boring,” and this prompts a great deal of soul-searching on her part. She questions whether he is right, and questions whether she should change as a result of his observation. The sisters meet two men in a bar, who invite them out on a boat the following day to dive with sharks. Lisa’s instinct is to decline, but Kate persuades her to agree by playing on her fear of being perceived as “boring.”

Arriving at the boat, Lisa is put off by its dilapidated condition, and the dismissive attitude of the skipper, Captain Taylor (Matthew Modine). She is again persuaded to participate, though, and the boat sets off from the coast. The two men they met at the bar dive first, after Captain Taylor pours bait into the water to attract sharks. Their dive concludes without incident, but when the sisters are lowered into the water inside the diving cage, the cable attached to the winch breaks, and the women sink to the ocean floor – 47 meters down, and out of radio contact.

After a period of panic, during which they assess their rapidly dwindling oxygen supply, Kate exits the cage and swims upward seven meters to resume radio contact with the boat. Captain Taylor assures her that someone will dive down to reattach a cable, but that sharks are circling, so they should stay in the cage and wait. While they await their rescue, paranoia begins to set in, and they question whether they can trust Captain Taylor to respond to his moral obligation, or whether he might just sail off and leave them to die.

They spot a torch in the distance, and Kate exits the cage once more to attract the attention of their rescuer. Kate becomes disoriented, though, and is chased by sharks. Their rescuer is killed by a shark, so Kate grabs the spare winch and manages to attach it to the cage – swimming back upward to radio the boat to pull them back up. The cable snaps again, and the cage sinks back down – trapping Lisa’s leg against a rock. Kate swims and communicates this to the boat, at which point Captain Taylor tells them the Coast Guard is an hour away, and he is sending replacement oxygen down to them. He warns that this may cause nitrogen narcosis, though – which causes hallucinations.

The first half of the film requires the two women to place their trust in Captain Taylor, while the second half calls into question their ability to trust themselves. As hallucinations begin, it is impossible for them to distinguish between reality and imagination.

Open Water (2003)

Of all shark movies, Open Water is a particularly unpleasant viewing experience – not least because it is inspired by real events. It is, however, highly effective in telling a tale of futility, and the epic hubris of the human race.

Written and directed by Chris Kentis, Open Water takes its premise from the well-publicised, very real tale of Tom and Eileen Lonergan, who went on a scuba-diving trip to the Great Barrier Reef in 1998, and never returned. It is alleged that the excursion operator failed to execute an accurate head-count of the group returning to the boat, and that the Lonergans were left behind when the vessel returned to shore. The same fate befalls the couple in the film – Daniel (Daniel Travis) and Susan (Blanchard Ryan) – but the film fills in the blank, and depicts a likely fate.

Daniel and Susan are aware that, due to hectic lives and working schedules, their relationship needs some attention. This prompts them to book a scuba-diving holiday, as a bonding experience. They join a group of 20 divers, and dive for about 30 minutes. At one point, they separate from the group, without realising that the group then surfaces and boards the boat without them. When Daniel and Susan re-surface themselves, the boat is gone. The staff aboard the vessel miscount the number of passengers returning, fail to double-check, and set off for shore in the belief that everybody has been collected.

Stranded in open water, Daniel and Susan reach a number of conclusions. Firstly, the boat is not coming back; secondly, they have drifted a significant distance from their original dive site, so even if the boat did return, they would likely not be found; and thirdly, sharks are beginning to circle them. They cycle through various stages of panic and grief, and their wet-suits delay the pain caused by the fact that various small fish are beginning to eat them alive, while they are also being stung by jelly-fish. Eventually, a shark strikes Daniel, and he is killed during the night – although Susan continues to hang onto him.

In the morning, she realises he is dead, so she lets go of his suit and the circling sharks devour his corpse as he floats away. Susan puts her diving mask back on and looks underwater, to see that the sharks are moving toward her. Alone, and with all hope lost, she purposefully allows herself to drown, so as not to be eaten alive. Later, fishermen are slicing open a shark, and find the underwater camera belonging to Daniel and Susan, inside its stomach – and they speculate about whether or not it might still work.

The bonding experience sought by Daniel and Susan – intended to save their relationship – results in their gruesome deaths, because they opted for an activity that was beyond their egos. The couple were over-confident enough to think that they could split from the group of divers and that the group could be relied upon to notice they were missing. There are two elements at play here: firstly, the ego of humanity, in believing that technology allows for the exploitation of natural underwater habitats, for the purpose of tourism; and secondly, the ego of the individuals to be so wrapped up in their own experience, that they do not pay attention to those around them.

Daniel and Susan are seeking an activity that will allow them to bond with each other, but they fail to bond with anyone else in their diving group enough that anyone would notice they were not on the return boat trip. At the same time, rather than using the experience to bond with nature, they exploit a delicate eco-system for their own purposes – regarding it as a challenge to conquer an inhospitable environment, rather than respecting it as it as the territory of other creatures. Ultimately – and as a consequence of their hubris – Daniel and Susan become a part of that eco-system, which is not the kind of bonding they had in mind, but is bonding nonetheless.

Shark Tale (2004)

Shark Tale is unique in the shark movie genre, in that it takes the more traditional idea of sharks as movie protagonists, and subverts it into an animated children’s tale about the importance of being true to oneself – as opposed to pretending to be something you are not. This is layered with elements featuring the need to allow people to be different, and to not limit the potential of any individual. It is directed by Vicky Jenson, Rob Letterman and Bibo Bergeron, from a script by Letterman, and Michael J. Wilson.

The lead character of Shark Tale is a bluestreak cleaner wrasse named Oscar (voiced by Will Smith), who works at the local Whale Wash, while dreaming of fame and fortune. His best friend is an angelfish named Angie (Renee Zellweger), and she has a notable but secret crush on him. Oscar runs into debt with his boss, Sykes (Martin Scorsese) who operates as a loan shark, in addition to running the Whale Wash. Oscar’s attempts to gamble his way out of this trouble backfire, and cause more problems.

Oscar crosses paths with two sharks named Lenny (Jack Black) and Frankie (Michael Imperioli). They are the sons of Don Edward Lino (Robert De Niro), who heads up a particularly dangerous and brutal organised crime syndicate. Oscar is being tortured by two jellyfish associates of Sykes, but they flee when they see the sharks approach. The situation brings tensions to a head between the shark brothers, though.

While Frankie is a very violent heir to Don Lino’s criminal legacy, Lenny is a gentle-natured vegetarian who is constantly pressured and ridiculed by his dangerous family. On seeing Oscar being accosted, Lenny moves to help him, and Frankie becomes angered in his frustration at Lenny’s natural inclination to care about others. He charges at Oscar, but is accidentally killed by an anchor. Lenny flees the scene, and passing creatures see only Oscar with Frankie’s corpse. Oscar then becomes famous, and known as the ‘Sharkslayer.’

While Lenny and Oscar bond over their mutual secret, and Oscar takes full advantage of the fame and fortune he has stumbled into, the death of Frankie brings Oscar into conflict with Don Lino – who takes Angie hostage in retaliation. During an attempted rescue, a chase sequence ensues, and Oscar eventually traps Don Lino and Lenny inside the Whale Wash. With his community looking on, Oscar monologues to Don Lino about the virtues of Lenny, and the importance of accepting people for who they are. Don Lino concedes, and embraces Lenny, while Oscar makes peace with the sharks, Sykes, and Angie. And they all live happily ever after.

It is this redemption of the toothsome protagonist that adds to the uniqueness of Shark Tale within the shark movie genre. While it is the nature of most shark movies to see the protagonist retain its dead-eyed, cold-blooded killer status, the fact that Shark Tale is an animated family film means that the narrative can use that well-worn preconception to make its point in an even more dramatic fashion.

Sharknado (2013)

Many shark movies come in for ridicule – but few reach the heady, risible heights of Sharknado – a made-for-television, Syfy-network commissioned film so spectacular it has spawned five sequels in five years. The premise of this first film – written by Thunder Levin, and directed by Anthony C. Ferrante – sees a bizarre atmospheric phenomenon strike Los Angeles, causing a series of water spouts to form. These spouts suck hungry sharks out of the ocean, and bring them inland, in tornadoes and flood-water. A bar on the boardwalk, owned by Fin Shepard (Ian Ziering), is destroyed, and he sets off with a group of his friends/patrons to rescue his ex-wife, April (Tara Reid), and their teenage daughter.

There is very little else that needs to be said about the actual plot of the film, since it so closely resembles that of every other disaster movie in which a man is suddenly filled with the urge to prove himself to his ex-spouse by saving the day. The reason that Sharknado warrants inclusion in any list of notable shark movies is because it literally flips one of the core elements of the genre, and bases its entire concept on that subversion.

Most shark movies – particularly those that are high profile and well-known within popular culture – are based on human interaction with sharks taking place in shark territory. People, either on or in the water, are forced to reckon with these predators – placing those people in a situation where they are battling both a foe and the environment at the same time. In these instances, the sharks have the home-field advantage, as it were, and this is a key feature of the genre.

Sharknado subverts that entirely, by manufacturing a scenario in which the sharks are the territory invaders. The humans have the home-field advantage, and so we are given a tale that allows for sharks to be fought with military-grade bombs and a variety of other hardware, as opposed to those options being limited by a marine environment, in which such weaponry has to be improvised (as in Jaws). Though its premise is ridiculous, it does still manage to layer in some bigger themes, however – most notably that of climate change, as with any film about extreme weather in the modern age.

Indeed, Sharknado is proof that even the most outlandish B-movies can still deliver narratives that stand as significant contributions to the parent genre. Just when you thought it was safe to dismiss it…

Sarah Myles