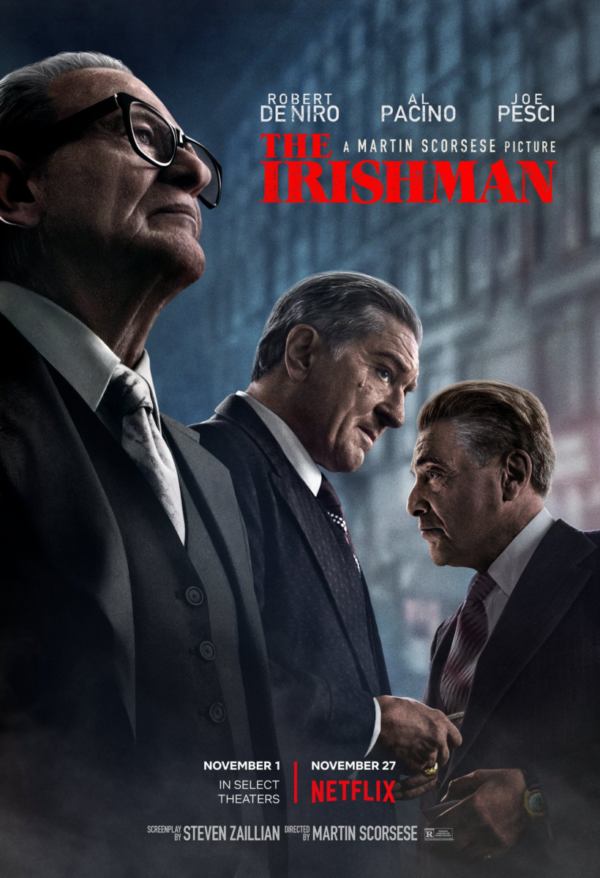

The Irishman, 2019.

Directed by Martin Scorsese.

Starring Robert De Niro, Al Pacino, Joe Pesci, Bobby Cannavale, Harvey Keitel, Stephen Graham, Domenick Lombardozzi, Anna Paquin, Ray Romano, Jesse Plemons, and Jack Huston.

SYNOPSIS:

A mob hitman recalls his possible involvement with the slaying of Jimmy Hoffa.

The gangster genre has existed almost as long as filmmaking itself has, and while it will continue long after Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman is in the cinematic rear-view, this towering crime epic in many ways feels like an ending of sorts, a definitive farewell to the venerated old guard of a genre these icons helped popularise.

At 76 years of age, Scorsese has delivered a film of such tireless vitality and filmmaking skill that, for fear of tempering hyperbole, one’s tempted to rank it among the very finest pictures he’s ever made. What’s clear above all else is that the director wasn’t simply interested in knocking out a complacent greatest hits reel and letting his central acting triumvirate do the heavy lifting.

This is a film which has something to say about both the evil that men do and the fate awaiting us all, and more so than any other film in Scorsese’s filmography, it’s a richly emotional treat as much as it is a visceral one.

Needless to say, don’t go in expecting Goodfellas 2, because despite the obvious debt it owes to that established narrative and visual language – the freeze-frames, gloriously, are back – The Irishman just isn’t that movie. The film opens with one of Scorsese’s signature long takes, passing through a nursing home to the sight of an aged Frank “The Irishman” Sheeran (Robert De Niro) as he begins to recall his storied life of crime, namely his introduction to mafioso Russell Bufalino (Joe Pesci), and his longtime friendship with labour leader Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino).

With its utter lack of flash, this tracking shot couldn’t be a more self-conscious inverse of the legendary Copacabana one-r from Goodfellas, and it’s brilliantly emblematic of the movie’s entire intent, to take the sexy cool of that movie – and most of Scorsese’s subsequent gangster flicks – turn it inside out and shake loose the underside.

In that respect The Irishman isn’t merely Scorsese’s most stripped-down and restrained mob movie – if certainly not in the runtime stakes – it’s surely his most self-effacing and even responsible, not that the filmmaker owes us the latter. This is a deeply unflattering depiction of the ultimate realities of a life of violent crime; an untimely or lonely death is all-but-guaranteed, the former indicated by on-screen titles detailing the time and method of the various’ mobsters’ demises.

And of course, Scorsese handles realistic violence better than almost any other director; even the big climax audiences will be anxiously waiting for is fittingly lacking in ceremony or exuberance. You might even call it banal; two pops, it’s over, and we move on.

The script from veteran scribe Steven Zaillian (Schindler’s List, Gangs of New York, Moneyball) is quite probably one of the most literate and nuanced the genre has ever seen. In various aspects the film draws parallels to all three Godfather movies; the epic scope of the first, the anxious tension of the second, and the chilly existentialism of the third. But in broader terms, the real-world context of Sheehan et. al’s operations are lent a wealth of due attention, namely his and Hoffa’s run-ins with the Kennedys, culminating inevitably with JFK’s assassination.

It’s stating the obvious to call The Irishman a film about America, but at a macro level the film does a marvelous job depicting urban decay and the operatic fight for the soul of a city, defined by the push-and-pull of crime vs. justice. An ice-cool sequence where Pacino’s Hoffa insists on re-raising the half-mast American flag in the wake of JFK’s death underlines that tension perfectly, to say nothing of a courtroom sequence which quickly devolves into media farce.

And despite its thoroughly serious excavation of the souls of some aging old thugs, Zaillian’s script is tremendously funny, laced with dark humour and creative profanity. The tone frequently flips on a dime, and does so with a preternatural nimbleness; one minute someone’s filling a watermelon with booze so as to get drunk undetected in front of Hoffa, who hates alcohol, and the next someone’s being shot through the face multiple times. Few filmmakers can handle this tonal bob-and-weave as well as Scorsese.

It’s totally unsurprising that this is an extremely long film, and even for Scorsese, 209 minutes is a challenging, bladder-annihilating sit. Thankfully this might be one of the most expertly paced 3+ hour films ever made, every scene leading into the next with a nervy energy, as so gracefully executed by Scorsese’s ever-present editing dynamo Thelma Schoonmaker, who will likely win an Academy Award for her stunning work here. It will, at least, be a consolation to many that The Irishman‘s impending Netflix release will allow viewers to impose their own intermissions, though the whole is so uncommonly transfixing you’ll probably not want to.

Credit is also due to Netflix and their penchant for letting artists make art, because as easy as it is to imagine a conventional studio insisting on Marty chopping a few-dozen of those long, lingering glances and held beats, allowing every moment to breathe and percolate for as long as it needs to is a vital part of the epic, all-encapsulating experience.

It’s barely worth confirming that Scorsese’s stylistic brio is in tact, for though the glamour is turned a few stops down compared to his usual, Rodrigo Prieto’s cinematography boasts a flavourful grit that perfectly nails the subtle era shifts, while sporadic, gorgeous slow-motion sequences are about as showy as the visuals ever get. The sound package is also far more subdued than you might expect; the Rolling Stones are nowhere to be heard, but a wonderful score from Robbie Robertson – who last collaborated with Scorsese on 1986’s The Color of Money – slyly accentuates the atmosphere.

The performances are, predictably, uniformly fantastic. Robert De Niro imbues the entire film with a slow-building fluster, embodied through his various stutters and tics when placed in a bind, while ably selling Frank’s transformation from comparatively spry to old and frail.

Joe Pesci, who was coaxed out of retirement at Scorsese and De Niro’s behest, gives a markedly different performance than many will be expecting; gone is the hot temper and wise-cracking wit of Goodfellas’ Tommy DeVito, replaced with a stoic, steely intensity that’s no less compulsively brilliant. His most poignant work similarly unfurls in the film’s third act, and despite the soul-shaking angst these scenes inspire, it’s a crowd-pleasing delight to see Pesci back with his two finest collaborators.

And then there’s Al Pacino, who comes storming through The Irishman like a whirlwind, tap dancing on a razor’s edge as he delivers a performance braced perfectly between Oscar-worthy and voraciously scenery-devouring. It is ludicrously entertaining in any event; a volcanic performance among his most compellingly modulated, pinballing between reckless aggression and disarming calm.

His verbal sparring with Stephen Graham’s Anthony Provenzano half-way through the movie might be one of the most gut-bustingly funny scenes from Scorsese’s entire catalogue. Pacino doesn’t show up until almost an hour into the movie, and history dictates that he’s absent from the final stretch, but the center is held firmly in his grasp whenever he’s on screen, and drinking games will surely be made out of his all-timer profane tirades.

And that’s not to forget an incredibly decorated supporting cast; the aforementioned Graham holds his own wonderfully opposite a titanic performer like Pacino, while Ray Romano adds another dramatic feather to his cap as criminal lawyer Bill Bufalino, Jesse Plemons is wonderful as Hoffa’s confidante Chuckie O’Brien, and Domenick Lombardozzi is amusing, if slightly jarring, kitted out in heavy prosthetics as Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno. Disappointingly, though, Anna Paquin appears for just a few brief scenes as Frank’s disapproving daughter Peggy, and she’s the single character in the entire movie who feels insufficiently developed given her import in the protagonist’s life.

It’s also worth briefly noting the film’s contentious digital de-aging techniques, which have been employed to make the central trio look many decades their own junior. Though the extreme de-aging does indeed look thoroughly imperfect to the point of over-smooth distraction – especially when De Niro is briefly seen as a young soldier in World War II – the effect is mostly employed to subtle ends, and succeeds in slyly demonstrating the steady passage of time, accounting for the film’s lack of on-screen timeline indicators. The digital makeup ultimately makes the advanced aging of De Niro and Pesci’s characters in the movie’s sepulchral third act that much more startling.

And it’s the landing which Scorsese really sticks best, because it’s at this point where the film most significantly diverges from the director’s prior work. Deep into The Irishman‘s final reel, the filmmaker delivers a soul-wrenching reminder of the impermanence of everything, and an end that can only occur in varied degrees of acceptance and loneliness.

It’s impossible not to view these scenes through the aged eyes of Scorsese and his stars, themselves edging towards 80 years of age. And while there’s sure to be debate about whether or not this was intended to mark a curtain call on their collaborations, there is an affecting finality here that comes full circle without deigning to slushy sentimentality. Above all else, it’s tough to imagine a more appropriate final shot for a project this all-encompassing of not only a man’s life, but eras bygone – both historical and cinematic.

The Irishman is a flabbergastingly ambitious, haunting deconstruction of Scorsese’s own prior mob movies, with De Niro, Pacino and Pesci turning in their strongest work in years.

Flickering Myth Rating – Film: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ / Movie: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★

Shaun Munro – Follow me on Twitter for more film rambling.