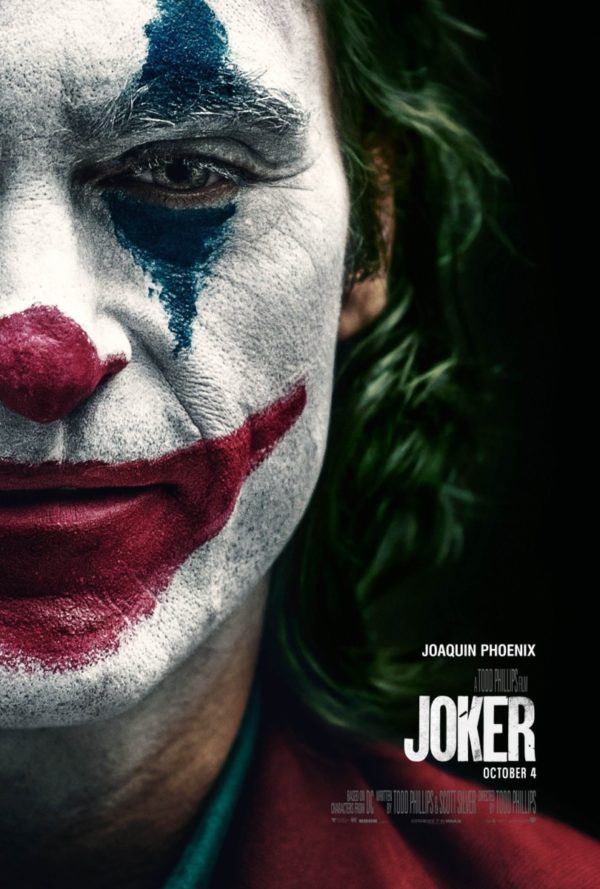

Joker, 2019.

Directed by Todd Phillips.

Starring Joaquin Phoenix, Zazie Beetz, Frances Conroy, Robert De Niro, Marc Maron, and Brett Cullen.

SYNOPSIS:

Forever alone in a crowd, failed comedian Arthur Fleck seeks connection as he walks the streets of Gotham City. Isolated, bullied and disregarded by society, Fleck begins a slow descent into madness as he transforms into the criminal mastermind known as the Joker.

When Heath Ledger’s Joker told audiences that “Gotham deserves a better class of criminal” in Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight, it was a statement that proved profoundly if unintentionally meta; Ledger’s posthumous Oscar win cemented his rendition, and the Clown Prince of Crime himself, as a seemingly unbeatable superhero movie antagonist.

There have been scarce other greats amid the many also-ran comic book movie baddies – the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s Thanos (Josh Brolin), for one – yet there’s just a single superhero foil whose name can even dare be whispered in the same sentence as Hamlet, and that is indeed The Joker.

A wonky Jared Leto rendition later and we arrive at Joaquin Phoenix’s gritty new effort, as helmed by The Hangover‘s Todd Phillips – a combo weird enough to be immediately compelling, for sure. And the good news is that Joker is in many ways fearless and uncompromising, shot through by a typically mesmerising Phoenix and the most sepulchral, dread-infused tone of any mainstream release this side of Hereditary.

In 1981, mentally ill, eking-by Gotham City resident and clown entertainer Arthur Fleck (Joaquin Phoenix) is in a bind. Neither his life nor his job are going anywhere; he still lives with his mother (Frances Conroy), and within moments of his introduction in the movie, he’s promptly assaulted by a gang of teenagers while simply trying to do his job.

Over the course of Phillips’ film, Arthur’s mental state cascades as he struggles to maintain strong, supportive relationships, and finds himself at odds with numerous quasi-paternal figures, including revered talk show host Murray Franklin (Robert De Niro), who at once mocks Arthur’s lame stand-up routine and takes note of the perverse public interest in his eccentricity. You need only look at any other Joker movie ever to have an idea of where these various lit narrative fuses are headed.

There is so much to unpack within Joker, and to a point that’s sure to quickly become exhausting, there will be harsh critiques and defiant defenses on both sides of the political spectrum. Is the film a screed for “incels” and the types who end up opening fire on schools, restaurants and even movie theaters?

By this critic’s perception, not at all. Phillips’ tone, which pinballs between stark gloominess and a Kubrickian, detached ironic joy – to the extent of playing Gary Glitter’s “Rock and Roll Part 2” as Arthur dances maniacally on some steps – won’t be for everyone, that much is clear. For others, they may struggle to take the pleas of Arthur, a white male, to be “seen” totally seriously, given the current quests by marginalised groups to be represented in mass media projects such as, yes, superhero movies.

Some will see Phillips’ failure, or rather his disinclination, to precisely label Arthur and his pathology as cowardly, yet the director seems decidedly more interested in speculating on the confluence of forces which brought the man to this place; an abusive upbringing, a lack of a father figure, mental illness, and an uncaring, materialistic society which cares little for the sick and poor. Picking a clear-cut answer would be too easy, and as Arthur knowingly says himself, “Why does anyone do anything?”

It’s the film’s class commentary which strikes the fiercest while perhaps being the most on-the-nose, however; the closest thing to an antagonist Arthur faces throughout the film, aside from his own demons, is Thomas Wayne, played with a delightfully self-satisfied slickness by Brett Cullen. As a wealthy and transparently careless politician, he’s a laughably blatant Donald Trump substitute, yet serves as a broader example of society’s collective lack of empathy towards the downtrodden, which can in many cases lead to tragedy.

As a piece of filmmaking, this is a major step up for Phillips, who with the sharp tonal left-turn he made in the latter two Hangover movies aptly demonstrated he was keen to deviate from the comedies that made his career. Reunited with regular DP Lawrence Sher, the film frequently invokes the grainy New York (that is, Gotham City) of Scorsese – who was originally set to executive produce – to say nothing of its shameless parallels to the legendary filmmaker’s own Taxi Driver and The King of Comedy.

And while Phillips is no Marty, he certainly came to this project with something to prove, and the result is a shockingly measured and formally precise piece of work, operating in tantalising tandem with one of our greatest living actors.

In fact, it’s when Phillips tries a little too hard to wink at the superhero crowd that his grasp on the whole slackens ever-so-slightly; Arthur of course has to briefly encounter a young Bruce Wayne (Dante Pereira-Olson), and there are other nods to the wider DC universe – though not the DCEU, mercifully – which may prove divisive with audiences.

Its greatest triumph, conversely, is making a guy in clown makeup running around a metropolis feel completely everyday and believable. The clown’s rise as a Tyler Durden-esque cult symbol feels a tad too expedient, for sure, but in an age where people don V for Vendetta masks as a joke and gatecrash Area 51 “for the memes”, just how unbelievable is it really that a chaotic clown could become an icon, ironically or not, for the many unwanted?

Again and again, it’s Phoenix who levels things out, gamely making Arthur a fascinatingly chilling spectre of a character, a figure who engenders such a wide range of emotions throughout the film; empathy, sadness and, ultimately, fear. The movie’s consequent-yet-brief bursts of bloody violence are treated with all the solemn power they deserve from both director and actor, steering away from grandstanding histrionics and favouring a far more enervating, even upsetting, tack.

To compare Phoenix’s work to that of Ledger’s is relatively futile; the two are so markedly different, sensibly, with Phoenix opting for a more physically visceral, skeletal “loser,” lacking the memorable tics which so wonderfully accentuated Nolan’s exuberant blockbuster. Phoenix makes all the right choices to service the material, and it wouldn’t be remotely surprising if he remained a Best Actor Oscar front-runner all season. It’s wonderful work, no matter your opinion on the whole.

Elsewhere, Robert De Niro turns in an uncommonly low-key performance as Franklin, perfectly cast in the very role that Jerry Lewis played opposite him in The King of Comedy almost 40 years ago. The result is some of De Niro’s best work in years, even if some may be expecting a larger or showier role for him.

Watching the film in a packed press screening was quite the surreal experience indeed, if only for underlining the dangerous potential of Phillips’ vague through-line. Moments in the film that, to this critic, felt desperately sad, were met with uproarious cackling by others, and one can’t help but wonder whether or not the film is destined for a Fight Club-esque mass “misunderstanding.”

Will Joker end up on countless “Coolest Movies Ever” listicles over the next decade like Fincher’s masterpiece? We’ll have to wait and see, yet the glib shallowness with which some audiences may approach the material, in unavoidable part because of that superhero movie label, surely says plenty more troubling about the people watching than it does the movie itself.

Sure to ignite fierce debate on both ends of the political spectrum, Joker is bold and provocative in measures that make even the grittiest superhero tentpoles seem safe. Joaquin Phoenix is a revelation.

Flickering Myth Rating – Film: ★ ★ ★ ★ / Movie: ★ ★ ★ ★

Shaun Munro – Follow me on Twitter for more film rambling.