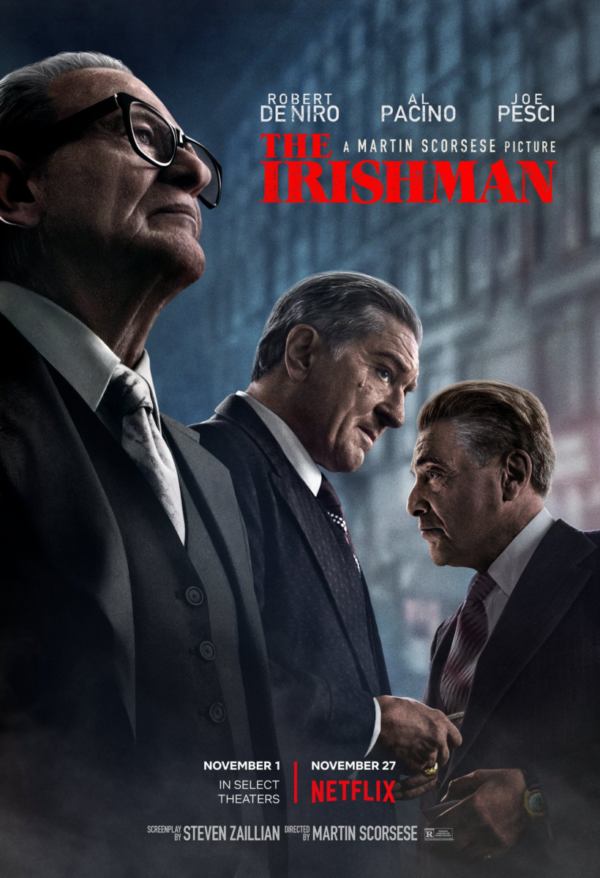

The Irishman. 2019

Directed by Martin Scorsese

Starring Robert De Niro, Al Pacino, Joe Pesci, Bobby Cannavale, Ray Romano, Stephen Graham, Kathrine Narducci, J.C. MacKenzie, Craig Vincent, Anna Paquin, Gary Basaraba, Jesse Plemons, Jack Huston, Domenick Lombardozzi, India Ennenga, Joseph Russo, John Cenatiempo, Larry Romano, Sebastian Maniscalco, Rebecca Faulkenberry, Stephanie Kurtzuba, Jeremy Luke, Natasha Romanova, Louis Cancelmi, John Scurti, Welker White, Kevin O’Rourke, Bo Dietl, Jennifer Mudge, Paul Borghese, and Harvey Keitel.

SYNOPSIS:

A mob hitman recalls his possible involvement with the slaying of Jimmy Hoffa.

Frequently throughout The Irishman, there are freeze-frames of various real-life mobsters delivering details on the death of each individual. On one hand, it’s always nice to have the historical aspect of a narrative, especially one as grandiloquent and sweeping as this one, expanded on, but that’s hardly the intention here. Barely anyone makes it out of the mafioso lifestyle alive to die of natural causes; at some point the whacking and other crimes catch up in one way or another, leading to a sudden grisly demise. Is it all worth it?

This is one of many elements that make this particular mobster epic from legendary filmmaker Martin Scorsese (partnered with one of his regular scribe collaborators in Steven Zaillian, both adapting Charles Brandt’s book I Heard You Paint Houses) a different kind of chronicling of mobsters. Although I’m not fully on board with the following line of thinking (protagonists in Scorsese’s violent masterpieces typically always face a reckoning of sorts), a movie like Goodfellas could be seen as glamorizing that lifestyle and indulging in the excess splendor. There’s never necessarily a happy ending, but Scorsese takes his sweet time and has fun getting to the inevitable downfall of his tragic “heroes”, a term to be used loosely. The Irishman goes in further in that direction to paint a secondary portrait entirely; one of legacy, regret, numbness, loss, reflection, and lonely pain.

The first 90 minutes see Martin Scorsese in his comfort zone, as we are introduced to Frank Sheeran (Robert De Niro, playing both his de-aged younger self, 1970 set present-day self, and his wheelchair-bound elderly future self all with restraint and subtle grace despite the murderous nature of his jobs), a World War II veteran who goes from driving trucks to slowly working his way up the mafioso ladder (something he equates to one another, with the intriguing parallels demonstrated via the occasional flashback within a flashback) due to his acquaintance with Russell Bufalino (Joe Pesci, commanding his underlings with even more restraint and sternness than Robert De Niro, making for a stark contrast to what moviegoers familiar with Martin Scorsese’s body of work might be expecting). Through these connections, he also gains the support of Russell’s cousin, trustworthy attorney Bill Bufalino as played by a hilariously scene-stealing Ray Romano.

Frank tackles a series of odd violent jobs for the Bufalini crime ring, all of which would be throwaway set pieces in a film by just about any other director; whenever Frank deals with rival businesses, Scorsese knows how to make threats and displays of dominance known. There’s a segment here involving dumping a bunch of taxis into a body of water while also blowing up a nearby parking lot full of them, which is as exciting as the climax to most action movies. The dark humor of this underbelly lifestyle is not lost on Martin Scorsese, namely with a sidesplitting joke involving characters disposing of firearms into a popular lake with Frank’s narration proclaiming “there are enough guns down there to arm a small nation”. An equally funny visual confirms this, even if we already know to believe it.

Roughly an hour into The Irishman (trust me, it doesn’t feel like it), Al Pacino’s short-tempered and bombastic (just think of the Al Pacino roles that ask him to freak out something fiery and fierce) take on Teamsters leader Jimmy Hoffa is introduced, who is having a bit of a problem with everyone from opposing establishments to Jews to the Kennedys. Taken through the election and inevitable shocking assassination of John F. Kennedy, The Irishman re-contextualizes everything about that presidency; if you’re cheering on these characters (and it’s hard not to get someone caught up in rooting on the charismatic criminals), a part of your heart might sickeningly be happy about the assassination while wanting to pause the movie and take a shower for having that thought (which I suppose you can actually do if you watch the film on Netflix).

In regards to narrative, that’s really all that should be said about The Irishman. The ascension is there and once again glorified, but those easy-going living conditions eventually become to unravel. Characters are tested with either expressing humility and humbleness for probably the first time in their lives or letting power consume them to an early grave, family dynamics are put to the test (the strongest subplot involves Frank’s daughter Peggy, played by Anna Paquin later on as an adult, coldly distant and traumatized by her father’s brutal tendencies, but not without ironically taking a liking to Jimmy Hoffa as an idol/parental figure), difficult cards to play are forced into the hands of characters (there is a sequence where Frank is tasked with carrying out a devastating objective, and Scorsese lingers on every detail of the mission turning it into a nearly 30-minute exercise in suffocating tension), with the results of every life choice hauntingly put into perspective alongside its worth questioned. Remember, this is not just a narration from Frank, it’s a confession, and he’s wrestling a battle royal against every demon.

All of this builds upon itself like a Jenga tower that could come tumbling down at any moment, but under the direction of Scorsese compounds into something beyond triumphant. The final 30 minutes are gloomy with ethereal beauty. However, it’s more than just Scorsese; without his longtime editing collaborator Thelma Schoonmaker you have a 3 1/2 hour movie that will not flow from scene to scene (one of the strongest aspects is how relentlessly the viewer is pulled into every single scene) and will definitely feel its length. In structure, it could be argued that The Irishman is episodic, but good luck finding a point to want to put things on hold and break the immersion (this is probably doable on the second watch, but that first time is a hypnotic cinematic stun-lock that employs everything from trademark tracking shots to groovy period piece music).

The first 90 minutes of The Irishman is terrific and already better than most movies released this decade, but those last two hours profoundly layer these characters with a lyrical presence and message. It sneaks up on you thematically in ways that are more reminiscent of Martin Scorsese’s Christianity films rather than his graphically bloody mob epics. And not to say that Martin Scorsese only has two tricks up his sleeve, but The Irishman blends the best of those worlds to create something undeniably unforgettable; the final shot alone cements it as one of the most elegant and poignant treatises on mortality and the choices we make as human beings.

If you are Martin Scorsese you would have a bone to pick with Marvel as well; there’s just no comparing something this carefully and meticulously crafted with a bottomless well of substance to the next chapter in saving the world. I say that as someone that has no problems giving out high scores to those blockbusters. Even taking the 20+ movie cinematic universe into account, The Irishman, a film that tracks the lives of its central characters across six or seven decades and the culmination of those experiences, is far and away the most ambitious thing ever put the screen. The Irishman is a showstopper for different reasons altogether, and story beats within the movie itself hint at the iconic filmmaker genuinely afraid about losing history to time (not his own, but important historical figures and more). Fortunately, The Irishman likely won’t be lost to time; hey Martin Scorsese, I heard you like Oscars.

Flickering Myth Rating – Film: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ / Movie: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★

Robert Kojder is a member of the Chicago Film Critics Association and the Flickering Myth Reviews Editor. Check here for new reviews, friend me on Facebook, follow my Twitter or Letterboxd, check out my personal non-Flickering Myth affiliated Patreon, or email me at MetalGearSolid719@gmail.com