Graeme Robertson with five great films that should have been nominated for Best Picture at the Oscars…

Whenever the Oscar nominees are announced, the best and brightest of the film critic world (and idiot’s like me) gather together and begin our collective muttering about what film we feel deserves to win the Best Picture trophy.

While I can’t pass judgement on how deserving the latest crop of nominees are (because I haven’t managed to see all of them) it did get me thinking about all the films over the years that, despite being amazing and perhaps more deserving, didn’t receive a nomination for Best Picture.

So as we await the results of this years ceremony, we’re going to have a quick look at five great films that despite being among the best film of their eras, failed to receive a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Picture.

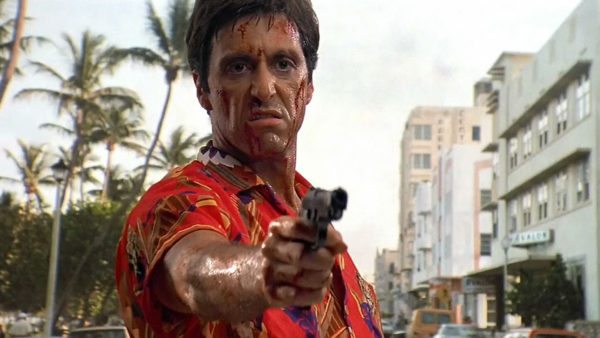

Scarface (1983)

A film much-maligned upon its original release for its brutal violence, morally reprehensible characters and an overabundance of profanity, Brian De Palma’s Scarface has since grown in stature to become one of the most popular and iconic films of the 1980s, if not, of all time.

A very loose remake of the 1932 classic of the same name, Scarface is a fast-paced, violent, foul-mouthed roller-coaster ride as we follow Cuban exile, Tony Montana, as he begins his bloody rise up through the criminal underworld to become the cocaine king of Miami.

The biggest reason to watch Scarface is to see Al Pacino give one of his most iconic performances as Tony Montana, a man who snarls like an animal, curses like a trooper and tears across the screen like a cocaine powered Tasmanian Devil. Pacino’s performance is hilarious, ferocious, frightening and always entertaining, his almost cartoonish Cuban accent making his every word a treat and his every f**k laden utterance never ceasing to raise a chuckle or two.

The script by Oliver Stone is peppered with bucket loads of profanity riddled one liners, many of them shocking, hilarious and endlessly quotable. Gems such as “First you get the money, then you get the power, then you get the women”, or “I only have two things in this world; my balls and my word and I don’t break em’ for nobody.” among many others.

De Palma’s direction is superb throughout, packing the film with various violent set-pieces including one particularly gruesome encounter with a chainsaw, before climaxing with an epic shoot out between an army of goons and a coke powered Pacino. The look and style of the film is also a perfect time capsule of the early 1980s, the garish fashion styles, the synth-heavy soundtrack by Giorgio Moroder that somehow manages to be both dated but also somehow miraculously timeless.

Scarface is quite simply one of the best films of Pacino and DePalma’s careers, one of the best films of the 1980s and one whose snubbing by the Academy is especially unforgivable.

Come and See (1985)

I talked about this one in a feature many years ago, but it’s a recommendation that bears repeating. One of the most brutal and horrifying depictions of war ever depicted on film and one of the most frightening films I’ve ever seen; Elem Klimov’s Come and See.

Come and See follows Floyra, a teenage boy living in Soviet Belarus who rushes off to join the partisans to fight the invading forces of Nazi Germany who are tearing across the country. What follows is an almost literal journey into hell on earth as Floyra struggles to survive in a world were death and destruction lurks around every corner.

Come and See is not a film for the faint-hearted. A fierce and unrelenting depiction of the horrors of the Second World War’s Eastern Front, one of the bloodiest in human history, the film does not shy away from graphically depicting of the brutality faced by its young protagonist. This brutality is worn on the face of lead actor Aleksey Kravchenko who begins the film as an enthusiastic young and youthful looking boy, but by the end, after everything he has seen, looks like an aged mentally shattered old man.

Supporting characters are far and few between, with the few we do meet often quickly killed off in the film’s numerous atrocities. The atrocities themselves are the stuff of nightmares, and sadly of history, as in one particularly torturous 20 minutes long sequence, we are forced to watch as an entire village of civilians is brutally murdered by a force of sadistic cackling psychopaths.

A truly horrific experience that leaves you shattered and broken by the end, Come and See is one of the most visceral and raw films and a powerful depiction of what horrors humanity is capable of inflicting upon itself. If you only see one of the films in this feature make it Come and See.

Barton Fink (1991)

Showered by praise by the Cannes Jury who awarded it a trio of trophies including the coveted Palm d’Or, Barton Fink is arguably the best film by the Coen Brother’s and, in my opinion, one of the greatest films ever made.

Set in 1941, Barton Fink follows the exploits of its titular character, a playwright who, after a scoring a major Broadway hit finds himself scooped up by Hollywood to write the screenplay for a wrestling film, only to find himself stricken by a crippling case of writers’ block.

Melding elements of horror, psychological thriller, Hollywood satire, romantic drama and even buddy comedy, the film is a nightmarish, hilarious, mystifying genre-defying masterpiece, the likes of which only the Coen’s could conjure up. The script brimming with subtle fascinating commentaries about topics as diverse as the writing process, politics, religion and film, while still managing to retain the brothers’ distinctive quirky humour.

Steering the film is a career-best performance from John Turturro as the titular Fink, a gifted playwright who seeks to tell the story of the “common man” yet also doesn’t seem to understand or want to listen to him, with the actor brilliantly portraying the characters gradual mental breakdown with tragic pathos and dark humour.

Stealing the show though is an enigmatic performance from John Goodman as Charlie, a salesman who acts as Fink’s “neighbour” in the eerily quiet hotel in which they reside. Goodman’s performance is difficult to describe, appearing in part as a reprise of his usual familiar comic roles, albeit with a subtle hint of menace. It’s one of the actor’s best and, without spoiling too much, his most frightening.

A beautifully weird genre hybrid that you can watch endlessly while still finding all kinds of wonderful new things to admire, Barton Fink is a masterfully crafted work of art whose brilliance I cannot adequately describe in words alone. Go and watch this one immediately.

Heat (1995)

A film that is often regarded as one of the best of its era and one that many agree should not only have been nominated for Best Picture, but that also should have won it; Michael Mann’s epic crime drama Heat.

Heat tells the story of Hannah and McCauley, a cop and the criminal he obsessively pursues, with the pair being brought ever closer together by a series of high stakes robberies.

While this literal take on “cops and robbers” drives the plot forward, the real meat of the film lies in the characterisation of the two men who, despite being on opposite sides of the law, find themselves to be very much alike. Both are deeply dedicated to professions in which they excel, but often a deep cost to their personal lives. It’s a rich story that Mann brings to life brilliantly thanks his meticulous script and his precise direction that perfectly balances the quiet emotional scenes with intense bullet-riddled shoot-outs.

Bringing these complex characters to life are Al Pacino and Robert De Niro in their first on-screen pairing as Hannah and McCauley respectively, with both playing to their strengths. Pacino revels in indulging his sometimes larger than life persona, while still knowing when to dial it down. De Niro, by contrast, opts to go the opposite route, playing his role with a quiet dedication that is better suited to his more reserved and emotionally distant character, while still managing to be a quietly menacing presence.

While it would be easy to spend the rest of this short review praising the terrifyingly realistic shoot-out sequence, in my view, the most exciting scene of the entire film is a simple conversation over coffee. It’s a brilliantly written, directed and performed scene, with Pacino and De Niro playing off against each other beautifully, the pair talking of their failings and their resolve to stop each other.

Boasting the first (and best) on-screen pairing of Pacino and De Niro plus superb direction from Mann at the peak of his powers, Heat is quite simply a masterpiece from its first frame to its last. The main question though is this; why the hell did the Academy dare to ignore this film?

Road to Perdition (2002)

Acclaimed director Sam Mendes already boasts one Best Picture winner on his resume, but I think we can all agree his debut is perhaps not the film that should have scored him his first Oscar success. Instead, I feel that the film that should have won him some Oscar gold is the comic-based crime drama Road to Perdition.

Based on the graphic novel of the same name, Road to Perdition takes place in 1931 as Michel Sullivan Jr discovers his father’s hidden career as an enforcer for a powerful Irish-American mobster. After an attack on his family, Sullivan is forced to go on the run with his father as they attempt to evade the elder Sullivan’s former bosses.

A slow-moving character piece, Road to Perdition ditches the traditional gangster tropes to instead focus on themes of father/son relationships as primarily shown in the interactions between Sullivan’s Jr and Sr, with the pair’s initially distant relationship giving way to a closer bond as they are forced to rely on each other for survival.

Cast against type, Tom Hanks excels in the role of the elder Sullivan, a far cry from his usual affable persona, Hanks slips into the role with ease making for a surprisingly intimidating presence, while still finding time to project that familiar warmth as the character begins to soften as time goes by. Stealing the film is the legendary Paul Newman as John Rooney, a powerful mobster whose initial grandfatherly air hides a ruthless and fearsome criminal overlord, dominating his every scene with a powerful and commanding presence.

On a technical level, Road to Perdition is beautiful from start to finish, boasting gorgeous cinematography, a captivating musical score and superb staging that creates scenes to move the soul. The stand out sequence comes in a near-silent rain-soaked shootout in which all these masterfully executed elements combine to create a haunting and poignant climax.

Road to Perdition is quite simply the best film that Sam Mendes has yet made, a simply breathtaking piece of cinema and one of the best films of the 2000s, and one whose lack of a Best Picture nomination especially hurts.

Graeme Robertson