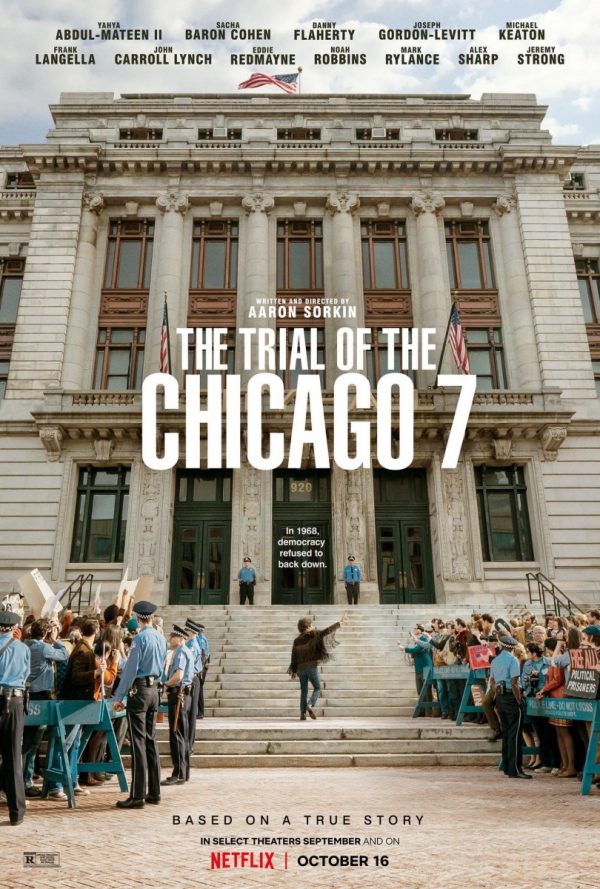

The Trial of the Chicago 7, 2020.

Written and Directed by Aaron Sorkin.

Starring Yahya Abdul-Mateen II, Sacha Baron Cohen, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Michael Keaton, Frank Langella, John Carroll Lynch, Eddie Redmayne, Mark Rylance, Alex Sharp, Jeremy Strong, Daniel Flaherty, and Noah Robbins.

SYNOPSIS:

The story of seven people on trial stemming from various charges surrounding the uprising at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Illinois.

It’s been almost 30 years since Aaron Sorkin first lent his pin-sharp pen to the courtroom drama with 1992’s A Few Good Men – adapted from his own 1989 play, no less – and so his latest project proves quite the creative homecoming for the acid-tongued writer, while reiterating the vitality of his unique voice.

The Chicago Seven are a group of anti-Vietnam War protestors (Sacha Baron Cohen, Jeremy Strong, John Carroll Lynch, Eddie Redmayne, Alex Sharp, Daniel Flaherty, and Noah Robbins) who were charged by the federal government in 1969 and 1970 on claims that they conspired to start riots in Chicago during the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Both sides agree that violent riots took place, but the crux of the legal argument comes down to one question – did the protestors start it, or the police?

As is true of a distressing number of period movies concerning social justice and the law, The Trial of the Chicago 7′s talking points are as pressing now as they were five decades ago. In an age where the President refuses to denounce white supremacists while dubbing protestors “terrorists” and more often conflating the two, a film which examines political labels, and the differing pursuits of justice makes for enthralling if not urgent viewing.

Sorkin makes a persuasive argument that the titular trial was more of a political show-piece for the Republicans than any sort of legal dispute rooted in a fair hearing of the facts. Just as he did in The Social Network – though by many measures much more terrifying – Sorkin languishes around in the dirty tactics and legal chicanery of the central circus.

This is especially true during a bile-inducing sequence in which it becomes clear the jury is being manipulated by outside forces, and another where a temporarily-accused eighth defendant, Bobby Seale (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II), ends up literally gagged in the courtroom.

Sorkin spends almost as much of the film considering the various branches of left-leaning social justice as he does the Sisyphean struggle for a fair trial. Naturally, there are differing perspectives and temperaments among the accused; those who cry out for civility at all costs, while others consider more direct confrontations with the police. Pragmatism clashes with idealism, and as is so often true in multi-stranded movements free of any discernible central voice, they can risk devouring their “own.”

It goes without saying that Sorkin’s script is full of breathlessly witty, overlapping rat-a-tat dialogue, packed with “Sorkin-isms” as it is – that is to say, dialogue designed less for real-life plausibility and more for cutesy, self-consciously affected zing. The characters are on-the-spot witty in ways real people never are; most of us will only come up with such clever comebacks hours or even days later in the shower.

Some viewers simply won’t vibe with this approach, feeling that it doesn’t lend itself as well to such a true, vital story as it does, say, the genesis of Facebook. But Sorkin is using his heightened parlance to draw the viewer in and, if we’re being honest, wipe the cobwebs away from a genre which has a tendency to be formal and prosaic.

There are definitely heavy-handed moments – particularly a scene in which the accused stop to solemnly observe a TV honouring soldiers killed in the Vietnam War – yet Sorkin’s sledgehammer approach ultimately does little to diminish the pathos of the piece. Quite the opposite, perhaps.

If Sorkin’s film as written feels very much within his typical wheelhouse, as director Sorkin has nevertheless grown considerably since his strong debut Molly’s Game, appearing more confident and ambitious in his approach. This is best exemplified by the near-whiplash-inducing pace at which the picture fleets back-and-forth between the courtroom and elsewhere – often for effect more comedic than dramatic.

As such, the film’s real hero might well be esteemed, Oscar-nominated editor Alan Baumgarten, who will likely walk his way to the Best Film Editing Oscar short of a miraculous surprise opponent. Much of the film’s impact – both as Serious Drama and more frothy courtroom yarn – lives and dies by his razor-sharp, brilliantly crisp cutting.

It need not be said, but the ensemble cast is indeed an absolute embarrassment of riches. Mark Rylance is typically outstanding as defense lawyer William Kunstler, an initially mannered attorney who slow-builds towards scarcely-contained fury. As stern opposing counsel Richard Schultz, Joseph Gordon-Levitt is an unexpected but effective casting pick, making Schultz a ruthlessly efficient and composed lawyer who finds himself wrestling between his job and his conscience.

The great Frank Langella is meanwhile brilliantly infuriating as Julius Hoffman, the Judge presiding over the case and whose mental state appears to verge on the edges of senility, and as his primary foil throughout, Yahya Abdul-Mateen II brings a wealth of righteous anger to the fore as Bobby Seale. Though Michael Keaton isn’t in the film for long, he makes firm, surprisingly hilarious impact as former Attorney General Ramsey Clark.

But beyond the bigger names, Sorkin has also stocked his film with a slew of talented character actors getting their licks in; the fantastic John Carroll Lynch is a treat as pacifist defendant David Dellinger, and The Wire’s John Doman gets an excellent early scene as irascible Attorney General John N. Mitchell.

On the slightly more middling side, Sacha Baron Cohen plays outspoken activist Abbie Hoffman, and brings an inviting warmth to the part, skirting clear of any inkling of stunt casting. However, Cohen’s accent also slips relatively frequently, and there are times where he feels more like he’s channelling Christopher Walken than the real Hoffman. As his compatriot Jerry Rubin, a scarcely recognisable Jeremy Strong also accounts for much of the film’s comic relief, though his deep-voiced stoner does feel only a step or two removed from caricature.

Though we as the audience don’t know it on a first viewing, Sorkin spends most of the film building a head of dramatic steam to a punchline payoff that’s at once totally hilarious and completely heartbreaking. And that’s The Trial of the Chicago 7 in a nutshell; a sassy, elegantly crafted example of an unfashionable genre, yet one which never loses sight of the case’s real-world, human impact.

A witty, charming, crowd-pleasing courtroom drama that’s passionately performed by a terrific ensemble and expertly edited for maximum impact.

Flickering Myth Rating – Film: ★ ★ ★ ★ / Movie: ★ ★ ★ ★

Shaun Munro – Follow me on Twitter for more film rambling.