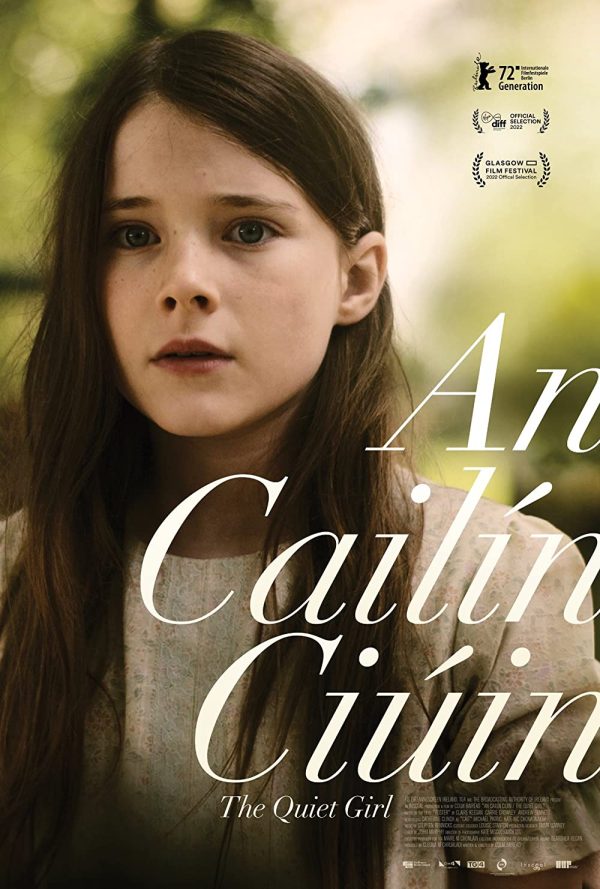

The Quiet Girl, 2022.

Directed by Colm Bairéad.

Starring Catherine Clinch, Carrie Crowley, and Andrew Bennett.

SYNOPSIS:

Living with more siblings than her parents know what to do with, unassuming Cáit (Catherine Clinch) is sent to live with distant acquaintances for a summer. Learning to navigate her own place in the world, the at times fraught Seán (Andrew Bennet) and ever-willing Eibhlín (Carrie Crowley) are able to coax Cáit out of her shell little by little. As time passes by and emotional bonds are formed, Cáit learns the couple’s past is not as it appears.

Even the most well-versed of cinephiles could count on one hand the number of films they’ve watched with an Irish Gaelic script. A muted dalliance between its mother tongue and juxtaposed English, Colm Bairéad’s The Quiet Girl is an effortless testament to the power of subtle and contained drama. Stunning in its vulnerable silence and extended shadow play, audiences are treated to a rare glimpse of a world through a child’s eyes where no adult has the emotional tact or command that should be bestowed upon them. Through frames of rolling hills and a wind that whistles louder than the voice of reason, a quiet cruelty reveals itself in the juvenile minds of adulthood.

With a sparse dialogue and slow-moving drama, it could be a surprise to see so many questions packed into a 94 minute runtime. Who deserves to be a parent? Who deserves to be a child? Living on the borders of rural poverty, Cáit has naturally blended into the background of the quiet chaos her parents and siblings effortlessly lap up. Her father shows an active disdain towards her existence, confident in his moral consciousness to leave Cáit with nigh-on strangers, even when her suitcase follows him home. Therein lies a self-righteous quandary of the bitterness in not wanting a child, with the family’s living conditions only further exacerbating Cáit’s forced upon disdain in existing. It shouldn’t be too much to ask for a moment of peace — it could be argued time to yourself is a societal right. Retreating to the overgrown reeds of surrounding isolated fields, Cáit is routinely looked down on for experiencing the world as it naturally comes to her.

What’s most interesting in The Quiet’s Girl’s visual canon is its extended use of height, shadow and facial recognition. As viewers begin to peek at who Cáit might be, her face is often obscured from view, covered by mounds of grass, hidden under a bed, or staring longingly from a long-forgotten window. It’s only when others approach her with eye-to-eye humanism that her complexion returns to the cinematic gaze, as if she has learned to deign them worthy of her time. It’s almost ironic that a rigidly lumbering farm can provide a place of sanctuary, unlocking the simplicity of child wonder with a filmic pause of breath to appreciate the little things. As Cáit comes to terms with parting from a place she can truly call her home, the stereotypical romanticism of winding car journeys is flipped on its head, acting as a reluctant return to a supposed right of place.

Though it can be considered predictable, the sense of homecoming dread is exactly what lands the film’s dramatic hooks. Thematically, the importance of cinematic message is held in the arms of ensemble performance, often blindingly delivered between knowing looks. Catherine Clinch’s Cáit speaks to an inner child adults have each embodied figuring out a world that is willing to leave her behind. Bennett’s Seán has the most obvious character development, blossoming from patriarchal standoffishness to a gentile man learning to love once more through Cáit’s mimicking out of admiration and respect. It’s arguably Carrie Crowley’s Eibhlín that holds the most narrative sway, simultaneously open-armed while subconsciously reinforcing the ideals of secrecy as shame. Together, the trio represent the beauty in the language of silence, perpetuating the dual need to belong and have something belonging to the self.

The power of saying nothing comes thick and fast in each of The Quiet Girl’s exquisitely crafted scenes. Imitations of the past rear their head to clear ghosts from the closet of the present, while death brings about a truth that entrenches a level of closeness Cáit has never experienced. There might be no use crying over spilt milk, but it doesn’t mean you have to settle for its remains.

Flickering Myth Rating – Film: ★ ★ ★ ★ / Movie: ★ ★ ★ ★

Jasmine Valentine – Follow me on Twitter.