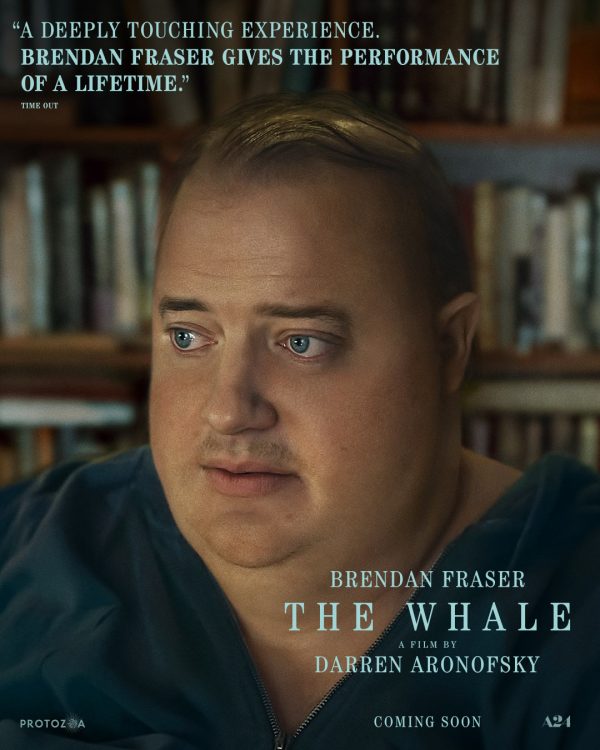

The Whale, 2022.

Directed by Darren Aronofsky.

Starring Brendan Fraser, Sadie Sink, Hong Chau, Ty Simpkins, Samantha Morton, and Sathya Sridharan.

SYNOPSIS:

A reclusive English teacher living with severe obesity attempts to reconnect with his estranged teenage daughter for one last chance at redemption.

How do you prove to someone that, deep down in your heart, you love them despite your past mistakes?

In Darren Aronofsky’s The Whale (based on the stage play by Samuel D. Hunter, also adapting his own work), Charlie (a career-best mesmerizing turn from Brendan Fraser, quickly overcoming the entirely believable and detailed but initially distracting bodysuit and makeup prosthetics) is a 600-pound literary professor educating college students remotely online, shying away from revealing his appearance. And while I’m (and I would assume most people) nowhere near that size, I do manage a physical disability, once having felt similarly about not wanting to show myself in gaming group chats (it might have been close to a few months before I let people see me on PlayStation Network) or conducting interviews with filmmakers and actors. There’s a preference not to want to draw attention to such things, hoping that people perceive you based on your words and actions.

The point is that people from all walks of life struggle with image, even if it’s not as severe as Charlie’s. One doesn’t need to be that large of a human being (a visual accomplished with greater effect due to DP Matthew Matthew Libatique utilizing an Academy ratio, cramming characters and facial close-ups into tight spaces) to pull something universal from his decision to teach with a “broken webcam.” There’s also a payoff to this that damn near broke me (and it wouldn’t be the first time I cried watching this).

Charlie also happens to be dying from a worsening heart condition with an estimated life expectancy of one more week, setting up a Monday- Friday structure that somewhat harkens back to Requiem for a Dream‘s seasonal chapters, just without time gaps. This prompts him to attempt reconnecting with his estranged 16-year-old daughter Ellie (a phenomenal turn from Sadie Sink that succeeds purely because we often feel the same way about her as other characters do; not understanding her thought process), who clearcut wants nothing to do with him.

Ellie despises Charlie. But not because he is obese.

A couple of events have led to Charlie losing control over his eating habits, primarily the loss of a boyfriend. Ellie sums it up as abandoning her and her mom to be with one of his students. That partner tragically died, essentially leaving Charlie with no one and nothing. To be fair, there’s nurse Liz (a powerful turn from Hong Chau, immensely protective over Charlie, believing herself to be the only one that can break through to him and encourage him to choose to get medical help), who treats him with humanity, the occasional harmlessly playful fat joke that they both appear comfortable with (slivers of comedy crack through here and there, which is essential considering individuals physically or mobility challenged sometimes have a dark sense of humor), and most importantly, dignity by respecting his choices.

Then there is New Life missionary Thomas (Ty Simpkins, also fantastic) going door-to-door and promoting end-of-the-world doomsday, who stumbles across Charlie in such a dire moment that he becomes convinced he is meant to save him. Charlie’s former partner Mary (Samantha Morton) also makes an appearance for one of the film’s most emotionally powerful scenes, of which there are several. If The Whale has a misstep, it is probably one sequence focused entirely on Ellie and Thomas (and one or two unnatural pieces of dialogue that could have been excised), although even that serves a greater purpose.

In a creative choice that will endlessly irk people or move them to tears, Charlie is overly optimistic and fixated on kindness, but values honesty, so much so that it’s the foundation that he implores his students to prioritize when writing think-piece assignments. Having saved up a sizable sum of money from teaching (he hasn’t told anyone about it), he wants to repair the damage between himself and his daughter, giving her all the money regardless of whether or not she puts in the effort. It’s the only way he can get her to stand to be around him.

The wrinkle in this plan is that over the past eight years, Ellie has transformed into a cruel problem child that doesn’t seem to care about anyone. There’s a point where Charlie instructs her to write something down, anything about her feelings as long as it’s honest, to which one line reads that she hates everyone, something that comes across as a relief to Charlie, knowing that it’s not just him she is brutal toward. She lobs hurtful statements her father’s way like hand grenades, is comfortable dropping hateful terminology directed at gay people (there’s a sense that her father leaving her for another man led her down a path of homophobia), and openly expresses not giving a single damn about catching up and getting close to one another again.

Meanwhile, Charlie insists to Liz, Mary, Thomas, and probably also would to the pizza delivery guy if he didn’t avoid stepping outside to talk with him that Ellie is a good and perfect person. To anyone with eyeballs and ears, she is a monster (played with grounded authenticity by Sadie Sink that would otherwise sink everything the story is attempting thematically). It’s also made clear by others that Charlie’s unwavering positivity in situations like this is oftentimes baffling, but The Whale is so sincerely invested in optimistic redemption, with Charlie so firm in his conviction that she is not a bad person and will come around, that once the film is over it’s impossible not to come away from this experience a kinder, more patient, better person.

Perhaps Charlie also knows Ellie is the only one being fully honest with him and telling him the things others won’t. She doesn’t mince her words or feelings, whereas Liz, as sweet a soul as she is, could also be seen as enabling by bringing him multiple meatball sub sandwiches with extra cheese, or someone like Thomas has a warped version of saving someone. There’s a deep uncomfortableness in Charlie’s face and expressive eyes (the only part of Brendan Fraser not covered in prosthetics, and brilliantly so) whenever Ellie picks up her phone and starts ignoring him unless he starts answering her invasive personal questions, which is seemingly the only way she is willing to reconnect while he is writing up essays for her to ensure she doesn’t flunk out of high school and promising her money.

This refusal to give up on Ellie as a decent human being capable of forgiving and caring about others also comes from the intelligence he sees within her, namely some dark humor at the expense of her writing and interpretation of books she reads for school. They are interpretations inappropriate for school work but a unique and honest analysis nonetheless. This is also a resiliency to give up on her rejection of love. As devastating as The Whale is to watch, it’s also a touching and delicate maximalist look at Charlie breaking down those barriers, searching for a shred of goodness in her soul, and trying to do something good before the film reaches its logical conclusion.

In execution, the ending is simultaneously on-brand for Darren Aronofsky and subversively uplifting. There probably won’t be a single dry eye in the house, and if, up until that point, you’re not sold on Brendan Fraser receiving awards recognition, you will be. It’s a transcendent, once-in-a-lifetime performance, with everyone at the top of their craft. No one finds beauty in misery like Darren Aronofsky, and The Whale is his latest stroke of mastery.

Flickering Myth Rating – Film: ★ ★ ★ ★ / Movie: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★

Robert Kojder is a member of the Chicago Film Critics Association and the Critics Choice Association. He is also the Flickering Myth Reviews Editor. Check here for new reviews, follow my Twitter or Letterboxd, or email me at MetalGearSolid719@gmail.com