William Stottor revisits the classic British horror-thriller Peeping Tom…

Before 1960, the Michael Powell half of Powell and Pressburger had enjoyed a commercially and critically successful directing career. Films such as The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943) and The Red Shoes (1948), which he directed with Emeric Pressburger, still rank amongst the greatest films ever made, but it would be a solo release in 1960 that would most drastically alter his career.

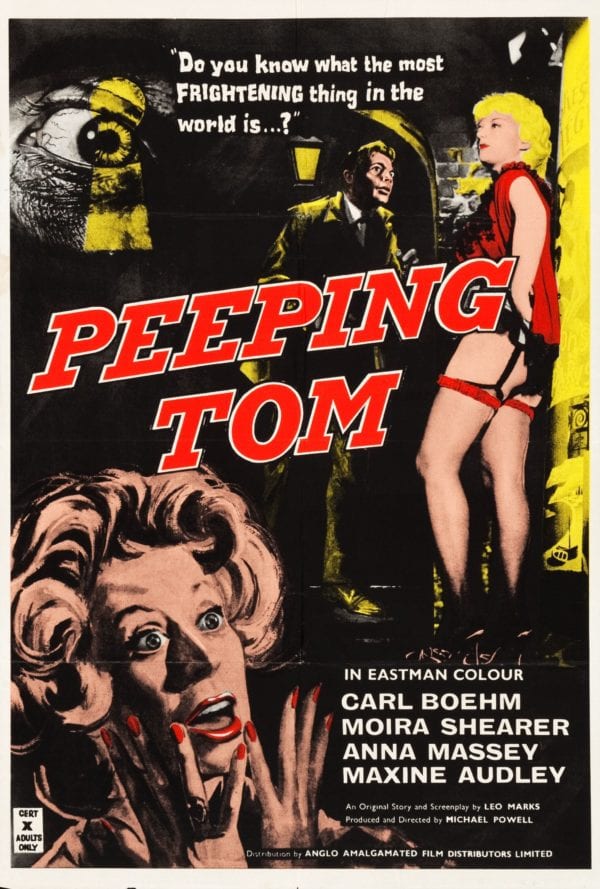

Peeping Tom released over 60 years ago, but only now are its controversial elements and shock value considered positives; at the time, reception was negative, the film vilified so much that it caused severe damage to Powell’s career. Peeping Tom is now considered a classic of the slasher subgenre—as well as one of the first examples—and it is also one of the most startling, brutal, and terrifying depictions of voyeurism ever shown on screen.

Why is Peeping Tom so frightening in its portrayal of voyeurism? Answering this will go some way in ascertaining why Powell’s film was so career-threatening upon its release. Written by Leo Marks, Peeping Tom tells the story of a serial killer living in London who stalks and murders women, filming the brutal acts with a portable camera. This dangerous peeping tom, this murderous voyeur, is Mark Lewis, brought to life in chilling detail by Karlheinz Böhm — soft-spoken, polite, seemingly harmless to the naked eye.

Böhm’s fascinating, layered portrayal of Mark conjures up a great deal of Peeping Tom’s dread, but further to that, the viewer becomes part of Mark. Peeping Tom opens on him murdering a prostitute, the entire act captured from the point of view of his camera’s viewfinder. Instantly, we are situated directly in both Mark’s vision and, more importantly, his psychotic mindset. Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window, which was released six years earlier in 1954, is a thrilling story situated around one man’s voyeuristic tendencies, but despite the viewer accompanying this protagonist constantly and being privy to his questionable snooping, he never commits any crimes, not least murder. In contrast, Peeping Tom slaps us right in the centre of the inner workings of a voyeuristic serial killer, and never lets us look away.

Peeping Tom’s insistence on maintaining the viewer’s direct involvement in this murderer’s life and actions will have contributed greatly to its controversy upon release. In hindsight, we can see its influence. John Carpenter’s Halloween, which was released 18 years after Peeping Tom, begins with a POV shot of someone committing murder—even more disturbingly, a six-year-old boy. There has and always will be a morbid fascination from viewers with murder and violence on screen, with Peeping Tom flipping this twisted intrigue back at us by sharing the events from Mark’s POV.

Mark’s actions are born out of his father’s psychological experiments on him as a child: he would study and capture Mark’s reaction to certain stimuli, often ones that were frightening. In a continuation of sorts, Mark now has a similarly despicable quest of finding the highest level of fear on a victim’s face. By including the viewer so directly within this voyeuristic journey, there is an intrigue as to what that fear might look like. We become part of Mark and Mark only, never of the victims. Aside from Helen (Anna Massey), a young woman living in the flat below Mark, the victims become blank canvases, which is both one of Peeping Tom’s weaknesses and one of its greatest strengths.

This climactic experience that Mark searches for represents one of the main reasons why Peeping Tom was so controversial on release: its glaring sexual undertones. Voyeurism is, by definition, based in sexual pleasure, although films such as Rear Window and its voyeurism don’t harbour these sexual notions. Peeping Tom doesn’t just reference the twisted, toxic masculinity of voyeurism; it angrily, relentlessly screams about it. Peeping Tom’s slasher groundings—its stalking murder sequences, tormented central man hounding women, bladed weapon—amplify these terrifying notions of sexual violence. Mark is a highly dangerous man, despite his reserved demeanour, and Peeping Tom, along with Psycho releasing in the same year, set the blueprint for slashers for decades to come.

In Peeping Tom, Powell uses the camera to enhance these sexual undertones. This filming device, so often viewed as a magical item that can create wondrous images for us to watch, becomes a thing of sheer ugliness, a phallic symbol of violence. The stand of Mark’s camera even elongates with a hidden blade, an extension of his masculine danger which is concealed at first glance. The contraption allows him to both murder and film. By instilling the dangers and perversion of the male gaze upon the camera, Powell was able to create something wholly disturbing, carefully but forcefully highlighting the connection between voyeurism and sexual violence.

Psycho was controversial and groundbreaking, but it never threatened Hitchcock’s career in the same way that Peeping Tom did Powell’s. On the face of it, two of the earliest examples of slasher films should have either lived or died together. It won’t ever become wholly clear why Peeping Tom was vilified so much more than Psycho, but the former’s unfaltering portrayal and linking of voyeurism and violence has to be one of the most obvious factors.

Each murder is felt in all of their gory, grim detail—every thrust of Mark’s blade, all of the victims’ terrified faces, the chilling way Mark stalks these women before they meet their hideous fate—so much so that Peeping Tom becomes more disturbing with every passing minute. By situating the viewer within the very mindset and viewpoint of a murderous peeping tom, Powell’s film, whilst disregarded in 1960, now stands as one of the greatest and most disturbing depictions of voyeurism ever seen in the history of film.

What are your thoughts on Peeping Tom? Let us know on our social channels @FlickeringMyth…

William Stottor – Follow me on Twitter