Released on this day in 1992, Tom Jolliffe looks back at Glengarry Glen Ross, a masterclass in screen acting…

The lights go down, the film rolls and everyone in the cinema (except THAT guy) go silent in anticipation of what’s to come. The film must then grip its audience.

The cohesion between writer, director and cast is further bolstered by other factors that can make or break a film’s success. Some films might rest on big set pieces, special effects, a grand scale and scope. You might call them necessary crutches for certain genres. Film-makers can further seek to manipulate the audience with careful editing, emotionally provocative music or twisting plots.

But what about when you take a simple idea, a day at the office of salesmen peddling real estate, confined to just a handful of drab and intimate settings and rest everything on your cast? It’s a little like theatre in fact and we’ve seen this approach on the cinema screens many times.

Sidney Lumet’s iconic masterpiece, 12 Angry Men did just this. The titular cast of jurors are confined in a room, as they deliberate the verdict for a complex murder case. Adapted from a teleplay, Lumet’s classic, often regarded as one of the greatest films ever, needed several things. It needed the exceptional script (from Reginald Rose), exceptional direction, but as much as anything, it needed a cast who could build tension, create emotion, and keep your attention.

No car chases, no asides, it rests entirely on a lot of unseen elements, the gripping dialogue and the likes of Henry Fonda, Jack Klugman and Lee J. Cobb giving exceptional performances. The film’s intimate nature has lent itself very well to stage versions of the tale too.

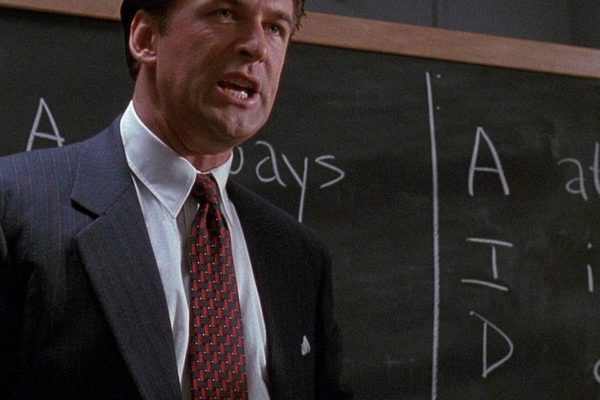

That theatre feel has often come by virtue of stage plays being translated to film. Among these is a film released thirty-two years ago today, Glengarry Glen Ross, adapted from David Mamet’s Pulitzer winning stage play, came with an all star cast and stayed largely true to the stage version (a major difference came with the inclusion of a new character, portrayed by Alec Baldwin).

The plot sees a group of struggling salesmen (with the exception of Al Pacino’s Richard Roma, on a hot streak) on a sit, about to receive a visit from someone from head office (Baldwin). We don’t delve greatly into most of these characters, beyond their manner, feelings and approach to the job, but Shelley ‘The Machine’ Levene (Jack Lemmon), we discover, is saddled with debts and hospital bills for a daughter. When the office gets robbed the police begin interviewing the sales force off screen, as the others deliberate what might be happening, or discussing their work.

Glengarry Glen Ross has a plot that reads fairly simply, but the power lies in great writing, subtle direction and the A-list cast all on top form. Mamet’s gifts as a writer are well known. A dramatist with an inherent gift in creating interesting drama with razor sharp dialogue.

There’s a distinct rotational feel about the film. The principal cast of Lemmon, Pacino, Baldwin, Kevin Spacey, Ed Harris, Alan Arkin and Jonathan Pryce are uniformly brilliant, but the film splits them into clusters, jumping back and forth between a number of conversations between 2-3 characters.

Among these we have Lemmon and Spacey, Arkin and Harris, whilst Pacino works his salesman charm on Jonathan Pryce having met him at the restaurant across the street from the office. The big set piece of the film is effectively a robbery we never see. It’s all about the acting.

Much is often said about Alec Baldwin’s barnstorming cameo. The fact it was created for the film makes it as close to a special effect as the film has. Baldwin is indeed a thunderous presence, playing the very epitome of toxic masculinity. He has the most quotable lines in the film. As a character, he’s pure cinema.

Pacino pushes Baldwin close for cinematic grandeur. Roma as a character is blunt, direct, duplicitous, gauche and charismatic. Pacino can fire plenty of bravado into roles, and this allows him to hoo-haa to his hearts content (brilliantly so).

Ed Harris plays a character of world weary, beaten down bile and pent up anger. A frustrated salesman on the brink of moral collapse. It’s a great performance from Harris, who has always been able to convey complicated anger very well.

Alan Arkin meanwhile is all neuroses, doubt and an inability to express his thoughts, and Spacey is perfectly cast as an effectively irksome slime-ball, doing his two faced shit-housery routine with aplomb.

Colourful characters expertly brought to life can take you so far, but within a story like this you need an emotional anchor. This comes in the form of Lemmon’s Levene. He’s a character we sense as having moral grounding. The fine, upstanding old schooler, appreciative of the old ways of selling, prior to the late 80’s infiltration of wall street bluster.

Levene’s growing desperation forces his hand and skews his moral compass as he makes a regretful decision. Levene wears his experience on his face. He’s respected almost as much for the fact he’s old, as anything else, by Roma particularly.

Jack Lemmon was always effortlessly likeable. He’s playing the most amiable character too, in a picture where Harris, Spacey, Baldwin and Pacino are meant to be more unsavoury (to varying degrees), we need a more amiable presence.

Additionally, Lemmon imbues Levene with a great warmth. He’s gentile, but can still find the conviction to take down Williamson (Spacey) a peg or two. That Levene ultimately loses in the film is a sad end to his tale. Lemmon though, in one of his last great roles, steals the film at a canter.

James Foley’s masterpiece certainly provides a dazzling example of some of the best acting of that decade, in a film of such simple elements. Many others have tried that minimalist, almost theatrical approach since, notably the engaging, if somewhat forgettable Humans.

What are your thoughts on Glengarry Glen Ross? What other films have the same stage play, yet cinematic feel as this? Let us know on our social channels @FlickeringMyth…