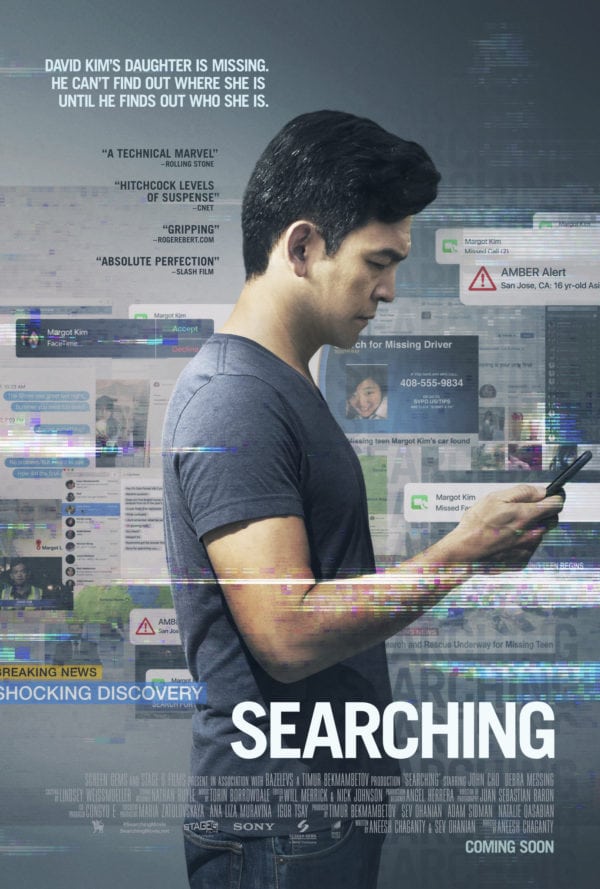

Red Stewart chats with Juan Sebastian Baron about Searching….

Juan Sebastian Baron is an American cinematographer who has been working in the film and television industries since the 2010s. He is best known for his work on the horror film The House on Pine Street and the recent thriller Searching.

Flickering Myth had the privilege to interview him, and I in turn had the honor to conduct it:

Mr. Baron, thank you for taking the time out of your day to speak with me. I actually just saw Searching, it was a great movie. Congratulations on the success.

Thank you, I really appreciate it.

One thing I found interesting in the credits is that there were two other cinematographers in addition to yourself, Nick Johnston and Will Merrick, but they were credited as the directors of digital photography. Obviously this means they were involved with the computer footage, but given the implementation of the real-life videos onto those screens, what were your interactions with them like during the production process?

Yeah, so I think that, as we were going through the process of making this film, Aneesh Chaganty realized, in a lot of ways, that there were going to be almost two, sort of complementary processes occurring at the same time. There was going to be the process of capturing all the live action footage, and then there was going to be the process of controlling the camera within the digital space of the movie. The way that this film was made honestly is more akin to that of an animated movie, because essentially the digital component of the screens and the devices was all generated by hand.

Oh.

That was all created, it wasn’t screen capture. It was animated, the way that you would do an animated film, because of technical limitations, but also because that was how they wanted to approach the movie from the get-go. When we started pre-production, and this is pretty unique, we went through the pre-production process with the editors, and they generated a pre-visualization of the movie using screen capture, and that sort of gave us an idea of what we needed to fill in: all of the video components that we needed to add.

But in the process of coming up with that, we had a lot of conversations early on about how we wanted to make this movie; what kind of grammar and language we wanted to have in this digital world. Initially, the production company, [the Bazelevs Company], approached us wanting the whole thing to take place in the entire screen all at once, in sort of what we’ll call it a wide shot of the whole screen. However, we knew that, in order to make this something you could watch for an hour-and-a-half and be compelled by, we had to figure out all the little grammar of what would a close-up be or how do you shoot a shot-reverse-shot of a conversation by punching in on the different FaceTime windows?

So that was something that we developed during pre-production. Once we wrapped regular production, there was a process of over a year-and-a-half where they really went in and animated and did a lot of camera moves in post. And it’s important for all of that to be seamless; like the stuff that we were doing in the live action had to feel consistent with the digital work.

That’s fascinating to hear that it wasn’t just a regular shoot, but two different ones going on at once. I did think something was off about this being screen captured when it was so clean, so it’s cool to know that it was actually animation. It looks so genuine.

It’s funny that you bring up animation, though, because the beginning of Searching, which was great and really set the mood, had this montage of family videos that reminded me a lot of the opening of Up. But even though they’re short, I imagine it must’ve taken quite some time to shoot all those scenes. Did you guys know beforehand from the script that you would need to create all this footage for the editing bay, or was it something you discovered during the shooting itself?

The opening was, from the very get-go, one of the most important parts of the original script because, the way Aneesh described it to me, the opening was going to set up the rules and teach the audience a little bit of how this movie was going to work. Like, we’re going to see FaceTime sequences, we’re going to see videos from outside, and we’re going to very rapidly lay out the grammar, the language, and the experience of watching the film, while at the same time giving background into the family.

The reference to Up was a big part of it because that intro sequence in Up really gives you a lot of context and background that informs the rest of the movie. So we really wanted everybody to understand the family at that point. It was very challenging because it’s a sequence that takes place over 10 years of this family’s life. And those particular years, from the early-2000s until just a year ago, have seen huge technological shifts; there’s been this huge cultural shift in media. It was a really fun opportunity.

I think, looking at that script and seeing all the different evolutions and little transitions that we could play with, so much of our approach to the rest of the movie really came from that, which in some ways was “well, do we want to shoot it all with a conventional camera and then grade the individual footage accordingly, or do we want to go out there and find camcorders from 2007 or 2008 and then try to mimic the look of old point-and-shoot cameras?”

And the latter was the road we took. It was a very short amount of time because of our pre-production schedule, but we really had to go in and go on eBay and buy old cameras and test them and figure out how the workflow would fit into the rest of the movie. And it was a lot of fun. It was definitely one of my favorite parts of shooting this movie, by getting to tell this self-contained story.

That hard work more than shows in Searching where, you’re absolutely right, it does have this older look to it. And I thought it was done in post, so it’s astounding to hear that you actually did this during principal photography. I actually remember my parents using those same cameras back in the day and how those aspect ratios looked and the feel of it in general, so I can safely say that you did nail it.

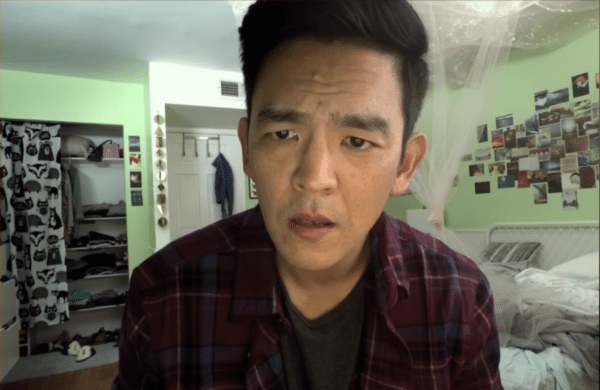

Yeah, I think there were little things, like when you look at the way an old camcorder zooms: the zoom has become such an integral part of that look and that style. And giving that camera to John Cho for him to operate and for him to go back in time a little bit and remember what it was like to shoot with a camera like that, to zoom in on specific things and be a dad in a way, it was really fun, it was really unique. It gives it a sense of authenticity that I don’t believe you can recreate any other way.

For sure, and you kind of answered another question I was going to ask, which was, because a lot of the scenes in Searching involve mobile cameras or FaceTime videos, did the actors themselves do the camerawork over your crew? Like that scene where David and his wife are jogging to fight the lymphoma or that part where he drives to the lake and he and the detective are yelling at each other through FaceTime. Were all those done by the actors themselves?

And I actually interviewed the filmmakers behind a Netflix film called Face 2 Face that also used GoPros, so I’m kind of aware of the process that goes into making a movie with them. But I’m curious, when it came to those first person selfie videos,

Yeah, that was a big conversation we had early on. And looking at other models, for example when Modern Family did an episode that all takes place with cameras and FaceTime, when they did that they had the camera operators themselves holding the phones, and the reason they did it that way was because you don’t want to give restrictions to your actors; you don’t want to say “don’t look over here because there’s going to be a light there” or “there’s no ceiling on this set so be careful.” You want to give them as much of an opportunity to act without worrying about operating this phone.

But in our movie, we knew how important it was to also liberate that aspect and not make it feel as rigid, so we had to just make sure that, yes, the actors were going to operate the phones, but all of the lighting and all of the conditions around them had to be such that they’d be able to point the phone in any direction and not have to worry. Which definitely meant that, in that night exterior scene on the lake, I really had to design the lighting to fit perfectly so that even if, for some reason, John would point it in some particular direction, it would be safe.

The biggest challenge we ran into with that is that you take these very traditional actors and you give them a camera that’s also showing them their face as they’re acting, and at one point we realized how distracting that was for them. So one of things we had to do was tape over the screen: you know when you’re in selfie mode you’re seeing yourself on the screen, so we had to tape that over. Which meant that, a lot of the time, we couldn’t tell if the camera was rolling or if someone had accidentally touched a screen and it was now focusing on something else. Sometimes the actors would accidentally press a button and the camera would stop recording and we would lose entire takes.

So there were some downsides to that technique, but I do think the quality shows in the film. And anytime we can remove ourselves from the process, the outcome is usually something that feels imperfect but real.

…Click below to continue on to the second page…