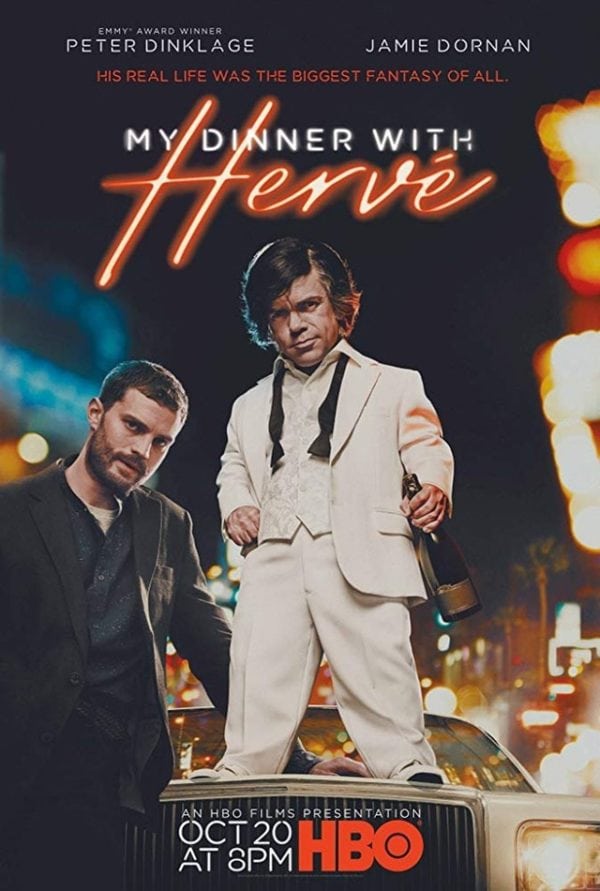

Red Stewart chats with composer David Norland about My Dinner with Hervé….

David Norland is an English composer who has been working in the television and film industries since the early-2000s. He is best known for his compositions for news programs like Good Morning America and 20/20, as well as other projects like What Would You Do?, November Criminals, and My Dinner with Hervé.

Flickering Myth had the privilege to interview him, and I in turn had the honor to conduct it:

Mr. Norland, thank you for taking the time out of your day to speak with me sir.

I genuinely appreciate the opportunity, so thank you.

Not at all. You’re the first composer I’ve ever spoken to who has done news shows, so I just have to ask how that process goes about? Obviously, you’re not playing live during a broadcast or interview, so do you learn of the topics beforehand and compose accordingly?

Generally speaking, what happens is, because all these shows are on a really short timeline, there’s a sense leading into them of what the topics will be. And so, I’ll get a call or an email stating “we need cues with this kind of a feel.” And sometimes it’s really specific. For example, there was a particular Barbara Walters special that I was doing that was, right up to the broadcast day, still being edited, and it was about this really tragic childhood disease, and they needed tragic cues, and so they suggested “we just need four tragic cues.”

So, it’s a tight timeline, and a lot of the time you’re not working to picture, meaning you’re reliant on strong communication of the underlying themes of the shows and what the producers and editors for those shows are looking for in order to succeed at it. And obviously, what happens is, as time goes on and you work more frequently with those producers and editors, you get to understand what styles and cues work for them for the pieces that they’re putting together, and that makes it easier. It’s the long-term relationships that allow you to effectively help and tell the story that everyone is telling at the time.

That’s interesting to hear. I hadn’t thought about how important interpersonal relationships are for a news show to come together, but when you think about the amount of time that’s being put into them and the, as you said, tight schedules, it makes sense that you would need to have those strong relationships to make the collaborations work smoothly. What is your primary tool for scoring these serials? Is it orchestral or do you work primarily with synths?

Well, that sort of digs into the alchemy of what it is to be a composer for film and TV these days, which I think is an essential part of a composer’s skill set now: to be able to make completely convincing orchestral pieces at your workstation. Having said that, though, the timeline nearly always precludes doing anything on a large orchestral scale. Whenever I can, I bring in players to my studio: string players, wind players, vocalists. I would much rather set up a microphone and record people than program all of those parts.

Having said that, the technology is good enough these days, and, like I said, it’s just an essential part of the composer’s skill set now to be able to, if necessary, produce a full orchestral piece without it ever existing outside of your workstation. And I can definitely do that, and definitely do that when called to.

That’s fascinating to hear. I’ve spoken to a lot of composers who were trained classically when they started off and, in today’s age, they insist that you have to learn to use programs. They don’t regret it, but it’s interesting to see the transition and necessity of digital compositions.

Right, and several things have driven it. Since it’s now possible to do that, for a film where obviously, the final score is going to be an orchestral piece that will be recorded with an orchestra, they don’t release the budget to do that until all of the cues have been approved in mock-up form. And so, to get to that point, it becomes an essential skill to be able to make those mock-ups absolutely true-to-life and realistic. And tools exist to do that, and now the skills exist to do that as well.

And it’s interesting because I had classical training in the early part of my life, and then took a hard-left turn when I discovered the electric guitar in my teens. But I’d had composition lessons at age 11, and all of those skills came back to serve me extremely well in the scoring process. However, the ability to make something out of nothing, which is sort of the rock ‘n’ roll side of things, has also served me extremely well.

That’s amazing to know. Now, you’ve gained fame for doing a lot of documentaries and nonfiction television episodes, as stated above. When you’re dealing with real-life events like that, how hard is it to transition over to a more Hollywood project like November Criminals or My Dinner with Hervé?

Well, the key difference is that it’s a different form of storytelling. I think in all these cases where the music is serving picture, ultimately storytelling is the key. And how the music serves it is the main aspect of the composer’s brief. To move to a film project, it’s a different form of storytelling because it’s one elongated narrative, and you’re working very closely as the composer with the storyteller, who is normally the director.

In the case of My Dinner with Hervé, it was Sacha Gervasi, who I’ve worked with for a long time. And because we’ve worked together so much and we’ve been making music together for picture one way or the other since we were kids, having that relationship really helped with the dialogue that’s at the heart of that process. You know, the composer’s job when doing a film is to be a brush in the hands of the director to help tell the story in the way that they want it to be told. If it’s not serving that purpose, it’s not really serving any purpose at all.

And so, it’s a longer and much more nuanced process than doing news music because it’s about, first of all, getting the musical language for the film right and the tonal palette that works for the storyteller and enhances their story in the way that they want. And then, this very detailed process of working together to work with the narrative and the emotional arc of what can be a two-hour story, and that’s very different, to very quickly putting together just a bunch of tragic cues or very dark destructive cues or very dramatic, powerful, action cues.

It’s a different discipline, and I would say that within making films and scoring films, it’s truly such a joy because the opportunity is to dig down into storytelling, and that’s the opportunity it presents. And Sacha’s always got these stories to tell, and he keeps taking me along for the ride. And I’ve had the opportunity to learn, at the time, how he likes to tell stories, how he likes to structure the kind of emotions that he’s looking for, and how music can serve that. And we get to do that on this extended timeline of the film, and in a really detailed fashion.

Also, I feel like I get this privilege, which not all composers get, which is I get to sit in the edit room as the editorial decisions are being made. And it really helps me see how stories are put together. It helps my art as a sonic storyteller, if you like, in the service of this bigger story that’s being told.

That more than answers my question. As you said, storytelling is what drives all the industries, whether it’s film, television, or the news media, and there’s definitely those connections. It’s also intriguing to hear that you get to sit in the editing suite, as I’ve talked to composers who’ve told me that they’ve had to change things when it comes to the final edit.

It definitely does, and I don’t know that composers are always given that particular opportunity because, quite often, I don’t think directors or producers want too many voices in the edit suite.

But I tend to shut up and listen in that circumstance, because what’s taking place there is the cogs of the storytelling actually in motion: you get to see it in the engine room. And that really helps inform my part of the storytelling process.

It’s always fascinating whenever I learn more about the process as a whole. I was going to ask how you got involved with My Dinner with Hervé, but I see you’ve had this long-standing partnership with Mr. Gervasi.

Yeah, for years and years. We were in our first bands together when we were in school; he was a drummer, I was a guitar player. We played some really dreadful concerts and went through that experience. When he was in college and I’d just flunked out, and I’d flunked out to be on the road with the band which, if you’re 19, do you go on the road with the band or stay in college? You go on the road! But he was still in college and he was involved in a production of Steven Berkoff’s East, a stage production at the college. And he decided that they needed music for it, and we knew each other and he came to me and we hired this ropy recording studio in London for a day and went in there together and made this crazy music. I had a few themes for it on piano and guitar and we knocked it out while he played the drums.

And we came up with this great crazy music that was very spontaneous and very unrestrained and just full of the excitement and joy of having the opportunity to tell the story with music. And we both loved it; we had this great time and the music came out great and it was a huge success in the production. And when, some probably 15-20 years later, he was making the move from being a screenwriter to a writer-director, and was directing his first movie, he asked me to do music for it. And it was beautiful and it was like picking up where we had just left off before. It was great.

Continue on to the second page…