Tom Jolliffe continues his series of beginner’s guides to legendary directors with a look at the work of John Carpenter…

What with the recent Halloween reboot in the cinemas, a 40 year anniversary for his original classic, and a series of gorgeous new 4K transfer releases for some of his other cult classics, now would seem a good time to focus on the work of John Carpenter. Considered a genre legend, he’s perhaps not fully acknowledged for just how skilled and visionary a filmmaker he was in his heydey.

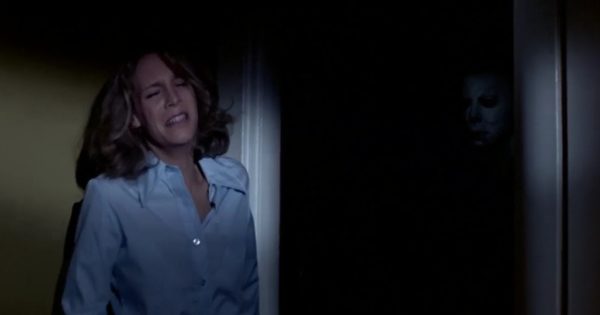

I grant you that there will not be too many who are completely unfamiliar with his work. Perhaps more so, this piece will be aimed at the younger readers, born after Carpenter’s career began free-falling in the early 90’s. For any look over Carpenter’s work, you’d say that Halloween is the point of entry. It’s the one that really broke him out in a big way. He’d gained a little notoriety with the low budget, oddball space comedy, Dark Star (an acquired taste), and then the tension filled and expertly delivered Assault On Precinct 13. Lets face it though, Halloween essentially re-wrote the book on American horror. It redefined a sub-genre and popularised the slasher genre, which until that point was confined largely to European (particularly Italian) cinema. It put all-American teens in peril, with a villain of mystique. Like many of the Giallo horrors which inspired Carpenter, a ghostly, faceless and relentless serial killer in Michael Myers would become archetype. If Halloween owed a nod to Giallo, then a whole sub-genre in low budget American cinema (especially when the VHS boom began) owed even more to Halloween. From Jason Voorhees, to every video nasty imitation (to countless sequels).

With a level of craftsmanship, careful photography, and tension, Halloween was as impactful as it was because of the level of artistry involved. Many horror films, many horror specialists, often get labelled as trashy. Occasionally it’s unfair, but what the video nasty boom saw was a churning out mentality among opportunistic cine-rebels, shooting on microscopic budgets, and occasionally without the cinematic love and eye someone like Carpenter had. Of course some fantastic directors did have the gift and broke out in the micro-budget horror world, like Sam Raimi and Peter Jackson. For the most part though, many of these directors were focused on exploitation over cinematic art. Again, this is why Halloween is still revered (and in addition, Jamie Lee Curtis’ magnetic performance) 40 years on. It would also set the tone for Carpenter’s subsequent feature work through the 80’s. His films looked amazing.

Carpenter as well as marking himself as a master of an entire sub-genre, would achieve cult status with the help of Kurt Russell. Two films in particular would help achieve this. The first of which was Escape From New York. A pulpy action thriller with Russell playing a Clint Eastwood-esque badass (with an eye patch) who has to rescue the President from a post-apocalyptic New York which is now a walled off prison. Carpenter enjoyed outlandish ideas, but like the thematically simple Halloween, carried them out with impeccable craftsmanship. Below everything too, there was also a sociological eye. His other major cult film with Russell would become a huge video favourite among people of my age. People love Big Trouble In Little China. It’s fantastical, it’s eye popping, it’s hilarious and it’s great fun. Again, a lot rests on the magnetic charisma of Russell as Burton. He’s the classic sardonic American schmoe hero. Long before Willis would become a specialist at it and kind of overtook Russell, a character like Burton was iconic.

SEE ALSO: John Carpenter lays the smack down on Dwayne Johnson’s Big Trouble in Little China sequel

Carpenter aficionados when asked for their favourite JC film are likely to segregate to two predominant camps. One is obviously Halloween. The other is The Thing (which followed his Curtis re-team, The Fog), the remake of the pulpy 50’s B movie. Given his gift for irreverence and B-film fun and thrills and an occasionally winking eye, The Thing could easily have turned out to be a light, gore focused horror. It might have been made with a looser grip given the subject. What Carpenter did though, was to treat the film with complete seriousness. To produce one of the pinnacles of paranoia horror. The film is made in an era of Cold War Paranoia, in Vietnam fallout/post Watergate recovery, at the end of a depression and in the birth of Aids paranoia. It all shows in the film.

The whole strength of The Thing rests in the inability to read what is happening behind the eyes of the person in front of you. It’s given literal power by the exceptional visual effects. Who to trust? Who is the creature from another world? Every reveal is grotesque. The visuals of course look amazing. Great photography, a classic ‘Carpenter score’ which on this occasion is actually by Ennio Morricone. Carpenter’s music, popular among 80’s synth score lovers in particular, was so organically melded to each film. It may have been the legendary Morricone in the composers seat, but the score itself felt very Carpenter. The Thing is a true classic and the biggest strength lies in Carpenters ability to draw scenes out in paranoid, uncomfortable, distrustful, fatalistic silence. It’s a masterpiece. I was fortunate enough to see in on the big screen a few years back and it’s impeccable in large format, with practical effects that beat anything a computer has ever produced in the genre. These are effects and transformations you can feel. They look horrifyingly painful. Just the same for example as the transformation scene in American Werewolf in London. It’s achingly painful.

The Thing would mark something of a turning point for Carpenter. From then on, his films were considerably more light for the most part (Prince Of Darkness would mark a switch back to more overt horror however). They bustled with comedy and a predominant aim of escapism. Not to say they lacked depth, but they were simpler films. The somewhat forgotten, Starman also saw Jeff Bridges give a fantastic performance as a titular ‘starman’ who learns human behaviour and it earned him an Oscar nomination.

Carpenter also helmed the Stephen King adaptation, Christine. It’s a daft concept, fully of typical King playfulness (a man becomes almost romantically synergised with his car). Though it’s silly, it remains something of an underrated Carpenter gem for me. Broadly stroked characters, a sense of fun, but at the same time (particularly if you get to see it in 4k form) it’s exceptionally crafted. The photography and production design is fantastic. It’s filled with great character actors like Harry Dean Stanton and Robert Prosky (and ‘Old Guy from Home Alone’). It may feature High Schoolers who look about 40 years old, but that was typical of the era. Carpenter draws you into scenes with slow, deliberate moves of his camera. It glides beautifully in impeccably lit scenes with an adoring eye on the central demonically possessed Plymouth Fury. The point is, as a visual craftsman, Carpenter doesn’t always get his dues, in an era which saw him duke it out with the likes of Brian De Palma, or Ridley Scott, Carpenter very much had his own style too. His peak era films thus look so slick, so clean, so organically put together that they have stood the test of time exceptionally well.

Some of Carpenter’s films, as I said before, have grown in stature through the years. One which has seen a marked rise from merely being seen as a popular piece of Video era hokum, to something a little more acerbic and insightful is They Live. There’s always been a certain cult appeal, but that cult is gaining in number, with reference over the years from everything from Duke Nukem games, Bart Vs The Space Mutants, to South Park skits. Carpenter was certainly brave in his choice of casting, opting to hand the lead role over to former WWE superstar and heel specialist (that’s bad guy in layman’s terms), Roddy Piper.

Carpenter’s dig at 80’s consumerism and capitalist obsession has slowly gained in notoriety over the years. Much like Robocop, it’s appreciated far more for the wry context beneath the surface, as a layered film and not just a one liner filled genre film. In addition, Piper actually exudes a vulnerability alongside the inherent charisma which made him a star in wrestling entertainment. It’s to a point, that it’s really surprising his career as an action man never particularly took off (he quickly descended into bottom barrel video premières). Unfortunately for Piper, They Live didn’t make many box office waves, whilst the other major film in his CV, Hell Comes To Frogtown was annihilated by critics (though it’s unabashed B movie sensibility and fun nature have attained cult appeal in this century).

As the 90’s rolled in, Carpenter’s inspiration and assured hand seemed to wane. Some films lacked a care and concise vision he’d always been known for (even when producing ‘B’ pictures). From a poor sequel, Escape From L.A to his final feature, The Ward, Carpenter, like many master craftsmen, just ran out of juice. However, his 70’s and 80’s work remains never less than enjoyable, and additionally, supremely crafted. His work in predominantly B picture genres means he’ll never quite get the respect his talents deserve among the critical elite, but regardless, to the fans who appreciated Carpenter’s inherent love for the B movie, few produced quite as many supremely crafted as he. He stayed largely loyal to those genres, whilst someone like Spielberg gained more respect in higher brow circles by branching out in the likes of The Color Purple and Schindler’s List. There’s no doubting he could have pulled it off in his heyday.

Tom Jolliffe is an award winning screenwriter and passionate cinephile. He has three features due out on DVD/VOD in 2019 and a number of shorts hitting festivals. Find more info at the best personal site you’ll ever see here.