The celebrated filmmaker’s crusade against streaming service film’s recognition at the Oscars seems to challenge the progressive strides being taken in the industry.

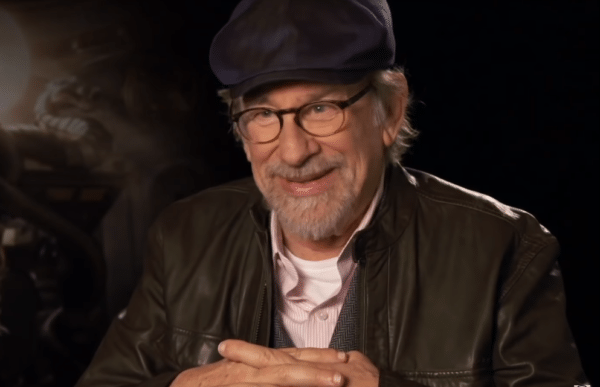

As a measure of how exciting my life is, I often ponder at length over how someone like Steven Spielberg spends his evenings. In my mind, I envisage him splashing around with a toy shark in a DeLorean-shaped bathtub, wearing an Indiana Jones fedora, blasting out a John Williams Spotify playlist while endlessly quoting the Jeff Goldblum “life, uh, finds a way” line from Jurassic Park.

While that all seems somewhat unlikely — it’s most certainly Robert Shaw’s USS Indianapolis speech he’s reciting — we can assume there’s one thing he’s probably not doing: watching Netflix.

Reports over the weekend indicate that the world-renowned auteur, the man responsible for our unwavering love for small aliens with glowing, elongated index fingers, is set to go toe to toe with the streaming giant at the annual Academy Board of Governors post-Oscars meeting next month. In the aftermath of last Sunday, a landmark ceremony not least because of Roma, a Netflix film, being in contention for the coveted Best Picture prize, Spielberg, as the governor representing the directors branch of the Academy, is said to be proposing changes to the criteria that enables films to be included at the biggest event in the movie calendar.

Roma ultimately lost out to Green Book on the night — a film that, coincidentally, Spielberg supported in this year’s Oscar race. But, despite the Green Book bewilderment, Roma didn’t go home empty handed: Alfonso Cuarón’s film triumphed in directing and cinematography, as well as picking up the award for Best Foreign Language film.

While many felt this was the very least the film deserved, a group of Academy members headed up by Spielberg, were quick to throw shade on its success by questioning whether films from streaming services should be allowed to compete at cinema’s most prestigious awards evening. “Steven feels strongly about the difference between the streaming and theatrical situation,” a spokesperson for Amblin Entertainment, the American film and tv production company co-founded by Spielberg in 1981, told IndieWire. “He’ll be happy if the others will join [his campaign] when that comes up [at the Academy Board of Governors meeting]. He will see what happens.”

After his comments in 2018 about films produced by video on demand services warranting inclusion at the Emmys and not the Oscars — “once you commit to a television format, you’re a TV movie” — this feels like Spielberg covering old ground. His recent claims, however, stem largely from an aversion towards Netflix’s 2019 Oscars strategy. Aside from the limited theatrical release of a film like Roma, the concern appears to derive primarily from the unrivalled $50 million Netflix allegedly spent in marketing for the awards season run-in.

Technically, Netflix and Roma did nothing wrong: its theatrical release was in accordance with Academy criteria — despite upholding its customary practice of not adhering to the traditional 90-day theatrical window — and there is currently nothing by way of a cap on marketing spend. But, aside from a distaste for Netflix’s lack of transparency over box-office figures and the more obvious threat to the studio status quo it possesses, it feels like, for Spielberg at least, this is coming from a much deeper, personal place.

In the same way films like E.T. and Ready Player One are moulded by a romanticised nostalgia, his own crusade against such platforms — bullwhip in hand most likely — appears to originate from his own engrained affection to the past. As much an unfaltering cinephile than he is a student of film making, it’s easy to picture little Steven as a wide-eyed youngster gleefully embracing the darkness of a movie theatre, gazing up at a large, illuminated screen, captivated by the action unfolding; immersed in a sweeping John Ford Western, or later, as a teen, gripped by fear while witnessing Marion Crane meet her maker while taking a shower.

And, in 2019, he wants to preserve the same cinema experience he was raised on. He wants to rescue the film world, as we know it, from what he likely perceives as the cold clutches of a movie-going experience reduced to scrolling through a multitude of remarkably niche Netflix sub-genres. It’s a selflessness that is undeniably admirable. But, just like the outlook of an Amity Island Mayor during summertime, it is also painfully naïve.

Speaking out against one of its finest might feel like the movie industry equivalent of blasphemy, but at a time of heated discourse around diversity, the attitudes of Spielberg and co. towards streaming services is altogether regressive. Directors like Ava DuVernay, whose Oscar-nominated documentary 13th and upcoming series When They See Us are both Netflix exclusives, have rightly hit back at such a stance on social media by highlighting the value of platforms like Netflix in promoting diverse film making and helping to fund projects that would otherwise struggle to be exposed to a mainstream audience.

The streaming behemoths have since responded, issuing a short statement on Twitter that, while not naming Spielberg specifically, read: “We love cinema. Here are some things we also love: Access for people who can’t always afford, or live in towns without, theaters; Letting everyone, everywhere enjoy releases at the same time; Giving filmmakers more ways to share art. These things are not mutually exclusive.”

Admittedly, it did give us Bright; but services like Netflix also opened the door for a subtitled, black and white, semi-autobiographical portrait of 1970’s Mexico, that conventionally would’ve been reduced to the eyes of a few tweed-wearing art-house addicts, to receive adoration from a vast, entirely new demographic of viewers. Given the conversations in Hollywood currently, why would the Academy not wish to celebrate such an endeavour? Equally, in a studio market dominated by big-money reboots, bankable franchises and folk running around in spandex nattering about infinity stones, without Netflix, what hope would there be for those independent, mid-budget movies with something different to say?

Spielberg doesn’t hate Netflix movies. He doesn’t hate streaming services. But he doesn’t think they merit the same recognition from the Academy, either. Netflix are far from the model student themselves; yet to exclude such films from contention for the industry’s most prestigious prizes solely on the grounds of distribution would mark one big, T-Rex-sized step backwards.

George Nash is a freelance film journalist. Follow him on Twitter via @_Whatsthemotive for movie musings, puns and cereal chatter.