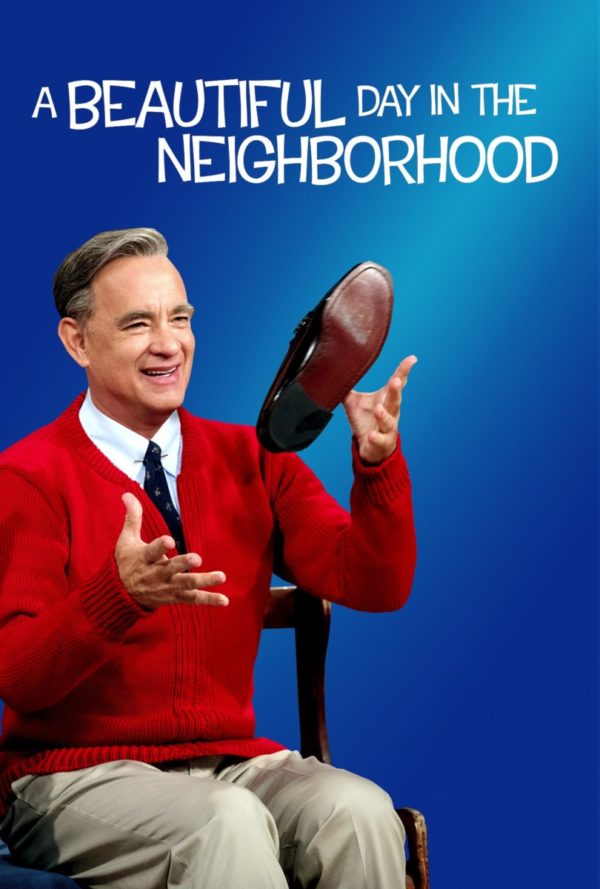

A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, 2019.

Directed by Marielle Heller.

Starring Tom Hanks, Matthew Rhys, Susan Kelechi Watson, Chris Cooper, Enrico Colantoni, Maryann Plunkett, Tammy Blanchard, and Wendy Makkena.

SYNOPSIS:

After a jaded magazine writer is assigned a profile of Fred Rogers, he overcomes his skepticism, learning about empathy, kindness, and decency from America’s most beloved neighbour.

In the hands of many filmmakers, it’s easy to imagine a saccharine, hagiographic biopic of legendary children’s TV star Fred Rogers, but rather than offer a mere syrupy distillation of the man wrapped in trite sentiment, director Marielle Heller (Can You Ever Forgive Me?) plumbs the duality of man and existential angst to emotionally shattering effect.

But to be clear, A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood is not really a Mr. Rogers biopic at all; it’s based on a 1998 Esquire article written by Tom Junod, who is reimagined here as writer Lloyd Vogel (Matthew Rhys), and whose wife tellingly says of his article late in the movie, “it’s not really about Mr. Rogers.” Heller uses the true story of Junod’s various meetings with Rogers to nimbly pivot the film around a journalist struggling to reconcile his anger towards his alcoholic, abusive father Jerry (Chris Cooper), while in the early throes of fatherhood himself.

Lloyd’s jaded mindset and shark-like mentality to his professional duties are contrasted with Rogers’ enormous patience and calmness of manner. Casting Tom Hanks in such a slam-dunk role only to push him into the supporting periphery is a risky approach, especially where Oscars are concerned, but one that absolutely deepens the emotional goals of the movie.

To call the film, to defer to a critical cliche, a “fuzzy, warm blanket” might suggest a frothy outing without much on its mind. There is a scene in this film where Rogers is taking the subway and a fellow passenger starts singing his signature song, “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?”, only for other passengers to join her. It’s a moment that could so easily come across as corny and ham-fisted, and yet, the sweet centre is girded at all times by thoughtful introspections on the human soul.

Heller’s film is deeply concerned with how we as humans decode our emotions – especially men, in this case – and if Rogers’ message about how best to express negative feeling penetrates through to even a single person in a meaningful way, then it has most certainly done its job well.

Rogers’ show was groundbreaking for its matter-of-fact exploration of dark subjects like war, divorce and death, and while this film only further bolsters Rogers’ status as an almost impossibly well-respected human being, it does provide hints at the man himself, even if truly private moments featuring Rogers – or his wife, Joanne (Maryann Plunkett), who is here only in cameo form – are in short supply.

Heller deconstructs the myth of Rogers just enough to be interesting, while taking to task the wave of cynicism present in society, and also insisting that an earnest mindset doesn’t need also beget ignorance. Rogers’ practised, near-monastic levels of composure and empathy are probably something most of us, with our fiery hot Twitter takes and impatience in a fast-moving, uncaring world, could aspire to.

Even more surprising than Hanks’ restrained amount of screen time, however, is Heller’s disarmingly surreal approach to the subject. The film is bookended by two pieces-to-camera in which Rogers, in the style of his TV show – complete with a fuzzy VHS-like aesthetic – reveals Lloyd’s troubled face on a picture board, serving as an at-once cutesy and affecting in to the movie’s real protagonist.

Elsewhere, charming practical models are used for establishing shots of city traffic, and in one delightful dream sequence, Lloyd even imagines himself as a prop within Rogers’ puppet show. This approach takes only one slightly iffy turn when Rhys briefly begins to imagine Rogers following him all around town, which comes off somewhat goofier than Heller likely expected.

Even though he appears in the film less than Rhys, this is absolutely Hanks’ movie, and while not much resembling Rogers physically, he pulls a Michael Fassbender in Steve Steve and instead does a marvelous job approximating his spirit.

Hanks nails the man’s soft-spoken demeanour and aura, enough that whether you’re particularly au fait with Rogers or not, you may find yourself fighting back a tear or twelve by film’s end – or even in the first two minutes, honestly. Furthermore, viewers will have to vice-grip their jaw in place not to crack a grin when Hanks’ Rogers performs a puppet show sing-song.

There’s no need to be disappointed when Hanks is off-screen, though – which many inevitably will be – as the void is filled ably by Rhys, who aided by the scripted and directorial nous on offer, takes a potentially formulaic, obvious father-son melodrama and renders something truly poignant. Rhys is a ball of rage and cynicism for most of the movie, playing splendidly off both Hanks and also Chris Cooper, who is fantastic as Rhys’ boozy father. Not letting Hanks do all the singing, Cooper even sings a half-cut rendition of Frank Sinatra’s “Somethin’ Stupid.”

Heller’s direction knows when to keep things simple and functional for crucial human moments and when to let loose with the topsy-turvy reality-breaking affectations. She also does a fantastic job evoking the analog era, with the artificially-aged TV show footage of Rogers escaping the crisp, clean tells of modern digital filmmaking; it’s a remarkably convincing effect. This is also true for the brief moments where Hanks is superimposed over archive footage of the real Rogers; the tech has clearly come a long way since the poorly-aged splicings of Hanks into historical footage in Forrest Gump.

The power of compassion, both to release yourself and others from anger, is unmistakable, and something many of us struggle with. It is a most basic facet of being human, as well as the fact we are all destined to die, as Rogers reminds us here. And these musings on our very existing, and what we do during that time, will likely sit longer with viewers than had the script simply settled for “be good to each other” Hallmark-style truisms.

Tom Hanks’ soulful, tender performance as Fred Rogers is enough to make the film sing, but what truly takes it to the next level is Marielle Heller’s dynamic, surprising filmmaking.

Flickering Myth Rating – Film: ★ ★ ★ ★ / Movie: ★ ★ ★ ★

Shaun Munro – Follow me on Twitter for more film rambling.