With it celebrating a landmark anniversary this month, George Nash takes a look at how The Green Mile’s tale of reflection and guilt still packs a punch, two decades on…

The year 1999 marked the end of the world. At least, that’s what people would have you believe as the clocks ticked ominously down towards the next millennium. Planes would supposedly start falling out of the sky, economies would collapse entirely, and prophesised Y2K computer bugs would tear down the fabric of society as we knew it. The panic was almost palpable. And yet, the final, fleeting moments of a century of conflict, mullets and the dawning of a digital age were also a time of poignant reflection, with humanity having as much to ponder about the past as to forecast about the future.

As has been the case for over a century, the mood of society was mirrored in the multiplex. From bullet dodging to iron giants, to underground fighting clubs which, ironically, we still can’t stop talking about, 1999, above yielding an impressive crop of critically acclaimed movies, encapsulated a timely blend of fearful uncertainty, excitement and warm nostalgia.

Released in December of that year was The Green Mile — Frank Darabont’s second of three feature length Stephen King adaptations to date. Dickensian in theme as well as form (King originally released it as a serial novel) the story, which takes place predominantly on the death row block of a Louisiana State Penitentiary in a depression-hit 1930s America, explores issues of criminality, innocence, religion and social tensions under the guise of a tale about magic, miracles and remarkable mice.

At its core, however, The Green Mile is a film about reflection. For its elderly protagonist, Paul Edgecomb (Dabbs Greer), his weary testimony to friend Elaine (Eve Brent) (in King’s book, it takes the form of a written memoir) derives from repressed guilt, triggered by a scene from Top Hat in which Fred Astaire sings ‘Cheek to Cheek’ to Ginger Rogers as they dance gracefully with one another — a moment that, for Edgecomb, shoots back painful memories like a bullet to the heart.

While the flashback has proved a popular trope throughout the history of Hollywood, here it becomes more than a simple structural device. Here, it is a wholly necessary thematic component of a story about guilt that serves as a powerful exercise in contemplation, set, rather appropriately, at the place where the guiltiest go.

As a death row prison guard in his younger days, Edgecomb (here played by Tom Hanks) is surrounded by guilty men. At the time we meet those incarcerated, however, they appear little more than muted, maternal souls awaiting death’s imminent arrival. Left with nothing but time, they are at the mercy of the ticking clock: their final days marked by a quiet, painful period of reflection as the seconds silently elapse before their one-way trip to the electric chair. Ultimately, it’s the weight of inevitability that hangs heaviest around their necks, turning even the most cold-blooded criminals — with the exception of Sam Rockwell’s maniacal “Wild Bill” Wharton — into docile, contemplative beings.

Unlike The Shawshank Redemption then – Darabont’s other adaptation of King’s other prison novel — where hope, however dangerous, still has a place in prison life, there’s an overwhelming sense of hopelessness in The Green Mile. Despite its fantastical elements, there’s a painful realism underlying the story that unfolds at E Block. Men are put to death without a whiff of redemption, and between false promises of fictional mouse cities and desperate desires to live eternally in the days that brought the most joy (as Graham Greene’s quiet, observant prisoner Arlen Bitterbuck sorrowfully muses) any thoughts or dreams that resemble hope exist in a time after death.

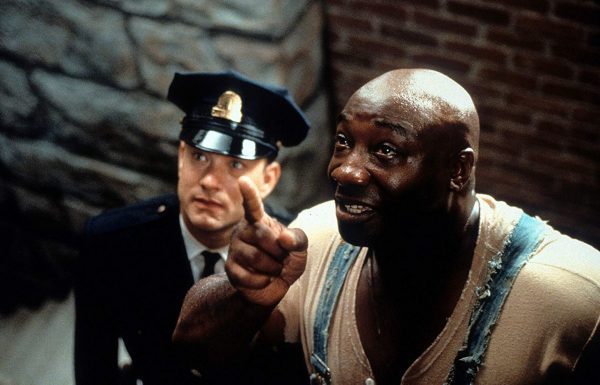

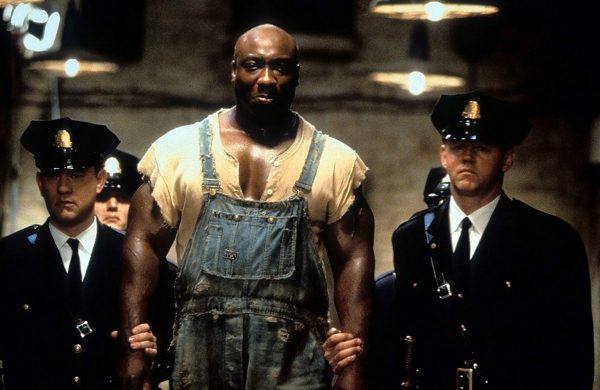

Only when The Green Mile reaches its final moments does its stinging irony become truly apparent. In the retirement home in which he resides — itself a form of prison — that same sense of guilt and longing for death eventually befalls Edgecomb himself. By his own admission, it is his punishment, laid down to him by the divine powers that be, for executing a miracle of God: the mysterious, gentle giant John Coffey (the late Michael Clarke Duncan in his most iconic role). It’s this idea, of the past casting a long, immovable shadow over the present, that lingers longest in The Green Mile; a notion that, as we reach decade’s end, continues to pack a real punch.

But, beyond the religious parallels Coffey’s execution draws (not least through his initials), it’s his innocence that hits hardest. In his death — a moment that invariably moves even the most stone-hearted of souls to tears — Coffey’s symbolism becomes twofold: at once representative of humanity’s history of unforgiveable injustice and the sins of one man’s past now plaguing his present. In the end, Edgecomb’s past actions condemn him to live a life riddled by guilt, not too dissimilar from those men he sent off to die all those years ago. However, his punishment is far more severe: time without a sense of finality. “Sometimes” he despairingly ponders on his own life as the film’s 3-hour run-time draws to a melancholic close, “it can feel so very long”.

In 1999, with one century coming to pass and another about to begin, the reflective nature of The Green Mile felt apt. But in 2019, as we each gaze pensively back over the last decade, while society tries to make sense of a turbulent, troubling ten years — a time of guilty men and past sins coming to light — The Green Mile’s powerful, haunting rumination on guilt has lost none of its potency twenty years on.

George Nash is a freelance film journalist. Follow him on Twitter via @_Whatsthemotive for movie musings, puns and cereal chatter.