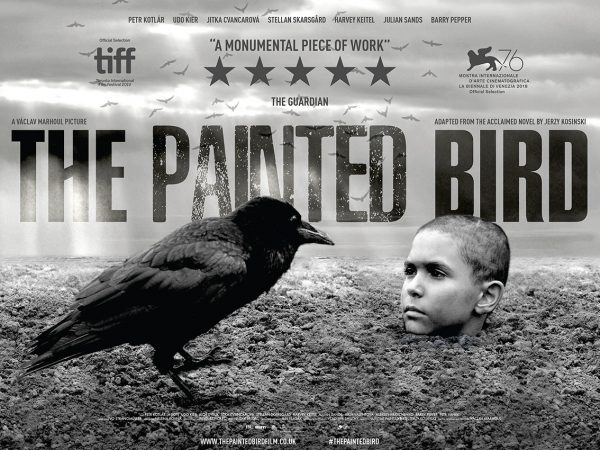

The Painted Bird, 2019.

Directed by Václav Marhoul.

Starring Harvey Keitel, Stellan Skarsgard, Barry Pepper, Udo Kier, Julian Sands, and Petr Kotlár.

SYNOPSIS:

Based on Jerzy Kosinski’s controversial novel, the story takes place on the Eastern Front during World War II, where a young Jewish boy encounters a living hell after his aunt dies and he accidentally burns her house down. The boy, Joska, is passed between a variety of misanthropes, sadists and abusers, as he comes to terms with the cruelty of those around him and also the realisation of Nazi and Cossack oppression.

The maxim ‘Hell is other people’ rarely finds such resonance as it does in The Painted Bird. Director Václav Marhoul’s austere, searing and lengthy adaptation of Jerzy Kosinski’s novel offers a seemingly non-stop procession of cruelty, both instigated by a wartime context and, even more disturbingly, without it.

Kosinski claimed to have based his novel on his own experiences, although this was later discredited. The film, however, is its own beast entirely. Rather than making a conventional anti-war statement, Marhoul seems to be at pains to point out that Nazi and Cossack tyranny, and its associated effects, is but one particular manifestation of evil. In contrast to such systemic, state-sponsored oppression, we regularly drift over to yet more baseless acts of cruelty and violence among the local villagers, whose exact motivations and ideologies are, if anything, much harder to locate.

Were it not for the presence of a biplane right at the very start, one could be forgiven for forgetting this is a war movie at all. Again, this seems to be an intentional move by Marhoul, shelving wartime iconography in favour of a more sweeping commentary on the banality of evil in all its forms. The film presents us with a black and white, Hadean portrayal of provincial madness, which could well come from any time, and any country. It’s through this landscape that persecuted young Joska drifts, portrayed to remarkable effect by untested child actor Petr Kotlár, who visibly calcifies and toughens as he endures a procession of shattering acts.

The contrast between the handsome, 35MM black and white photography, capturing flat, expansive vistas that seemingly stretch on for miles, and the horrendous behaviour going on in the foreground, only makes the film tougher to watch. For all the talk about 1917’s alleged one-shot immersion in a wartime hell (admittedly, that film focuses on a World War I scenario), Sam Mendes’ film resembles the Teletubbies compared to this.

Surely the closest comparison would be Elem Klimov’s devastating 1985 masterpiece Come and See, which jettisoned any such notion that wartime experiences can be shaped into a conventional, audience-friendly narrative. Rather, that film uses subjective camerawork and sound to craft a discordant, surreal, almost fairy tale-esque nightmare that feels far more horribly authentic than any story drawing on recognisable tropes and conventions.

The Painted Bird, for all its aesthetic differences, operates on much the same level. Shot in a polyglot Eastern European dialect (so that no one country or community is tarnished by association), it forces us to question these events, even as the camera refuses to turn away. Stories of mass walkouts at the Venice, Toronto and London Film Festivals are now legion, driven in no small part by scenes such as Udo Kier’s seething, cuckolded miller gouging out another man’s eyes with a spoon.

The Painted Bird, for all its aesthetic differences, operates on much the same level. Shot in a polyglot Eastern European dialect (so that no one country or community is tarnished by association), it forces us to question these events, even as the camera refuses to turn away. Stories of mass walkouts at the Venice, Toronto and London Film Festivals are now legion, driven in no small part by scenes such as Udo Kier’s seething, cuckolded miller gouging out another man’s eyes with a spoon.

Later on, Joska is abused by paedophile parishioner Julian Sands, who meets a grim end in a well full of rats. And a late sequence involving a brutal Cossack assault on a village alludes to the wider political situation of the time without ever explicitly spelling out why this is happening, enhancing the feel of senseless carnage. And as for the title, it refers to a moment where a sparrow, daubed in white, is subsequently marked for death by its own flock in mid-air, eventually plummeting out of the sky to its demise. If there’s a comparison to be drawn with Joska’s ordeal, Marhoul isn’t glib enough to flag it up.

Again, only a number of these sequences, particularly in the film’s second half, are explicitly linked to the spectre of the war itself. This becomes most evident when a captured Joska is set free by a stoic, silent German soldier (Stellan Skarsgard), and later still when he’s coached in the real cost of brutality by Barry Pepper’s Soviet sniper, the only halfway compassionate presence in the story, barring Harvey Keitel’s kindly but gravely ill priest.

Much as the stories of walkouts have drummed up a degree of notoriety, they don’t do this deeply compassionate film any favours. It doesn’t revel in button-pushing tactics, and never stoops to exploitation in its depiction of violence. (Indeed, much of the sequences described above are suggested, rather than shown outright.) The film is instead a humane plea uttered from the depths of despair and, as per the affecting scene with Pepper’s character, not to mention the quietly impactful ending (complete with the film’s sole use of music), it dares to imagine a hopeful way out of all this chaos.

Flickering Myth Rating – Film: ★ ★ ★ ★ / Movie: ★ ★ ★ ★

Sean Wilson is a film critic and journalist with a particular interest in film scores and soundtracks. Follow me on Twitter and Instagram.