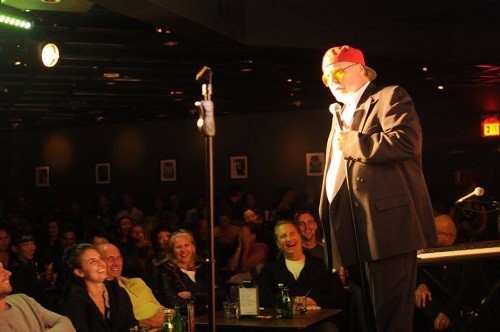

Martin Carr chats with comedian Richard Lett about his documentary Never Be Done…

In conversation Richard Lett is considered, eloquent and honest. His documentary Never Be Done is uncompromising, hard hitting and equally honest in ways words could never really convey. During our thirty minute conversation he was candid about recovery, pragmatic about his journey through addiction and grounded enough to know it comes down to choices you make. My hope is that this interview shines a light on the subject and enlightens those who rely on rumour rather than fact to make their decisions.

What was the thing that first made you want to get on stage and perform?

I didn’t have much choice actually because performing was just part of growing up in the Lett household. My family were all involved in music festivals and I was the youngest, so at six months old I sat holding my bear and singing ‘Teddy Bears Picnic’ in a family music competition, upstaging them all, destined never to be forgiven. My father was Principal of the high school where I grew up and my mother taught Music and English. There were four of us so by the time they got round to me, their way of doing things was pretty much set in stone. From there I did plays in high school then went onto actually pursue acting before becoming a drama teacher. However, when I graduated there was huge unemployment within the teaching sector, so a friend of mine encouraged me to try out at comedy open mic nights.

I have used comedy my whole life as a social lubricant either as the funny guy in a group or class clown, so stand up seemed natural for me very quickly and happened very easily. Within a few months I was getting paid for it, so that was the beginning of my meteoric rise at twenty six rather than in my mid-teens as frequently happens today. Purely because stand up in that form didn’t exist in the accessible way it does now. I do remember reading the book Ladies and Gentlemen, Lenny Bruce when I was in my teens, which inspired me to consider the idea of raging against the machine and make a living at it. As a result I fashioned my approach to stand up on him from the outset.

To what extent do emotional responses drive your creative choices, either writing or performing?

There is a perception that comedians make jokes about things because they don’t care about them, when in my experience the exact opposite is true. It not being dismissive when I talk about political issues or matters centred on race, either poking fun at them or bothering to discuss them on stage at all. When you look at masters of the craft like Richard Pryor or George Carlin, who I looked up to both intellectually and on stage they spoke with deep passion. George Carlin was livid most of the time and Richard Pryor was just broken and torn through his performances. That they expressed themselves with such eloquence and elegance was only possible because of this deeply emotional attachment to their subject matter; not from some intellectual pose.

In your opinion do you considering the documentary to be a cautionary tale or redemption story?

Both I would suppose. Cautionary in that you can believe your own press and the sickness which is evident within me watching it, is a spiritual sickness centred on ego. That entitles you to say and do things merely because you are being rewarded with laughter which is a seductive thing. A reward which at a certain point absolves you of any kind of responsibility for the harm being caused to others and to yourself. There is a point in the film when I am talking about this fictitious juggler who can only keep juggling by gouging himself in the gut. In order to stay at the top he must keep doing this and no one notices his injuries, but instead remain transfixed by his performance. That came from my own self-analysis in a very dark place describing myself as self-eviscerating for laughs.

Whereas redemption through recovery, almost without exception, is connected to a spiritual life. What we do is just our vocation in the world, but when we change our point of view of why we do things, whether that is the barista who does a brilliant job of making coffee, to the head of a corporation who invests time into his humblest employee that is where this change occurs. For me the reason to be this gregariously verbose man besides self-aggrandising, was to help others who might not have been given the charms of language or confidence to express themselves. When I do watch the documentary, which is not often, what comes through is its authenticity and honesty. Roy Tighe is a brilliant young director because the final time he takes me back to the car port, where all my stuff was piled up and asks me one more time ‘what was going on’ I can finally admit that I thought I was going to die so nothing mattered. That is the moment when I stop bullshitting long enough to admit that I didn’t care about myself.

From there people can hopefully relate and see elements of their own truth in that. In itself the relevancy of Never Be Done is due in no small part to the fact we are having this conversation now. So often we see these somewhat exploitative documentaries of people struggling with addiction through intervention. They cut to a commercial before coming back and this person has gained some weight, got a haircut and is having spa treatment somewhere in California playing volleyball, before a small addendum after the credits says he died. Whereas on this occasion I didn’t and many others besides make a full recovery, but in order to do that they have to change. A change which happens when people stop believing their own hype, in moments devoid of ego stroking enablers no longer there to encourage them. Everyone has loyal friends or precious family members who are left standing there wishing these friends could find recovery but dropped the ball. So in the documentary to think that my daughter Breanna was my reason is a nice sentiment, but there is no evidence to support it in what we see.

In the documentary you live through a period of brutal catharsis both personally and professionally, how important was it to have that on record?

It’s interesting because the belly of this beast and darkest part of that journey you never see. I simply disappear and only one phone call is there to explain my absence, which cinematically is perfect. Audience members are then forced to imagine my journey from their perspective and decide where that catharsis would be for them in each case. At this point the documentary takes on a universal theme which is best neither filmed nor put on screen. There was a point in rehab after a couple of weeks when I thought I would never do stand-up again. In group sessions after the first few days everyone is allowed to ask each other a question. So the first question was ‘what do I do for a living’ at which point I confessed to being a professional stand-up comedian. Every single question there after revolved around this, but one of them was ‘did I ever do it loaded’ and I said ‘yes of course but I prefer to do it sober because your timing is better’.

A couple of weeks later one of the counsellors asked me how I was doing to which I said ‘I’m still in denial, everyone is talking about stand-up and I don’t know if I can do it anymore’ and the counsellor said to me ‘you did say you prefer to do it sober’. A few days after that there was a monitor (someone also in recovery) who had gotten a job. This guy was working the midnight shift and I was up late in the smoke tent and he heard my often impersonated voice, came through and said ‘they told me there was a comedian here, but they didn’t say there was a real comedian’. He was a magician and a heroin addict which they often are, and he said ‘often I like to bring in my kit to do a show for everyone, so when I do the next one you can do fifteen minutes to warm them up’. Being in rehab after a while you pretty much say yes to everything so off I went and got together some jokes I could remember. Before going up instead of doing a line or drinking a shot which I used to, I did something unusual and praised that my words would be of service to the people that hear them. That calmed me down and in front of forty people sitting on donated couches I got up, made a few people snort, a few people giggle and then it took off.

Every story in or about discovery including this documentary has darkness underpinning it. Some of those guys who were there that night are fans of mine, who follow me on Twitter and Instagram, but then there are those that didn’t make it and you can never tell who they will be. Smart, kind and strong young men who are dead which is the grim truth of addiction. Alcohol is the worst of it and as much as we like to say that numerous people died from specific drug overdoses last year, those numbers are never documented for alcohol because it is so prevalent. Whether that is bleeding out due to the cell erosion alcohol causes, or those teenage girls who have been left in a place of depression who take their own life. These repercussions are endless and it is not very funny but in this documentary the cautionary tale and redemption story are thankfully interwoven together.

What was the first joke you ever told?

A joke where the dinosaurs went extinct from smoking and HIV, that was censored as usual but the other joke I had because I was teaching in school at the time went something like, ‘Kids in Grade 7 selling drugs; and the prices!’ That was a very Richard Lett joke.

Can you describe for me your perfect Sunday afternoon?

It would probably be lunch after church and a walk down to the beach for coffee. Then sit there with my lovely Lisa talking about myself and her listening, which she does being both her joy and burden.

Thank you for taking the time to speak to Flickering Myth and take care.

Never Be Done: The Richard Glen Lett Story is available to stream on AppleTV+, Amazon Prime Video and various streaming platforms now. Read our review here.

Martin Carr