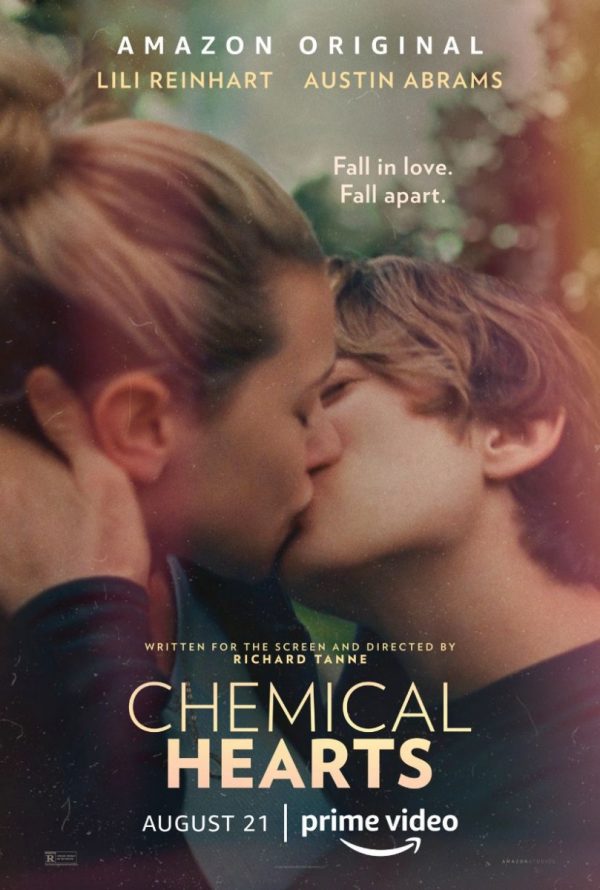

Chemical Hearts, 2020.

Directed by Richard Tanne.

Starring Austin Abrams, Lili Reinhart, Sarah Jones, Adhir Kalyan, Kara Young, Coral Peña, and C.J. Hoff.

SYNOPSIS:

A high school transfer student finds a new passion when she begins to work on the school’s newspaper.

There’s a recurring motif across Chemical Hearts, framing emotions as biological functions and chemical processes, breaking them down into hormones and endorphins and not a lot more. The almost-medical dialogue sits awkwardly in the film, the occasional references seemingly only included to justify the title, but even if the idea had been engaged with more deeply it’s not a framing device I’m especially fond of. Applying a scientific sheen to heartbreak and loss, romance and affection, joy and grief doesn’t render those experiences any more profound – it just makes them distant. Chemical Hearts is never cold, exactly, but it certainly doesn’t offer the intensity of feeling it promises in its opening lines: its characters are observed at some remove, never quite brought to life by a script more interested how they’re able to feel than what they feel.

That sense that characters are observed rather than engaged with isn’t, however, entirely a result of awkward dialogue: it’s baked into the film on a conceptual level. Chemical Hearts is yet another story that centres a white male ‘everyman’ type, positioning him as the lens to distantly approach a young woman’s trauma. If it feels familiar, that’s because it is. Chemical Hearts adapts the novel Our Chemical Hearts, part of a recent wave of Young Adult fiction that borders on the voyeuristic, where the specific tragedy their teenage protagonists have suffered is largely immaterial to the plot beats that follow. It’s not that there isn’t space for a sensitive, thoughtful film about a teenager rebuilding their life after trauma – or, indeed, about someone on the periphery of that – but Chemical Hearts isn’t that film. To its credit, it’s never as exploitative as the worst of its genre can be, and there are moments of relative quiet and maturity where Chemical Hearts distinguishes itself from those it most closely resembles, but ultimately they’re just that: moments.

Where the film impresses most is in its performances. I’ve long had the sense that Lili Reinhart will be Riverdale’s breakout star, and even if Chemical Hearts doesn’t prove to be the role that convinces everyone else of this, it’s a strong indicator of her talent nonetheless. On the page, her character had the potential to be, if not a Manic Pixie Dream Girl, then some spiritually similar equivalent – the fantasy Tragic Broken Dream Girl, perhaps, a bereaved and struggling young woman ready to be ‘fixed’ by our everyman protagonist. That’s still a significant part of the underlying text of the film, unfortunately; towards the end of its runtime, Chemical Hearts gestures at the problems with this idea, but never quite seems to believe them (if it did, you’d surely expect it to centre Reinhart’s character more). Still, Reinhart’s performance shines through these limitations. It’d perhaps be charitable to suggest that Reinhart gives her character interiority, exactly, but she manages to evoke a better film where the character might have had that – and offers enough charm and intensity that the script we did get is appreciably elevated by her presence.

Had Chemical Hearts committed more specifically to its lead characters, it likely would’ve been a better film; for all that the film focuses on its leads, it gets distracted by attempts to offer a much more sweeping, universal statement on What It Means To Be A Teenager. It doesn’t do so especially well, spending more time on blunt, lazy metaphors rather than on anything more substantial – wouldn’t the time spent discussing broken-and-repaired pottery be better used on, well, anything else? (If you didn’t realise the pottery symbolised Reinhart’s character, she helpfully points out that she “can’t be fixed, like your pottery”.) There’s something a little myopic about that, too – insisting the adolescence is a uniquely painful experience is unconvincing at best, particularly as it equates “being in a car accident and watching your boyfriend die” with “knowing the person who was in a car accident and watched her boyfriend die”. Again, there’s a thoughtful, mature film to be made about someone on the periphery of another’s trauma, but Chemical Hearts manifestly is not it.

Ultimately, it’s difficult to summon much enthusiasm for Chemical Hearts – positive or negative. Its depiction of trauma is bland and uninspiring, but hardly the worst that Young Adult fiction has offered; most of its flaws have a certain “this isn’t the first film to do this, and it also won’t be the last” quality to them. There are, as already noted, certainly some impressive moments worth remarking on, and Lili Reinhart excels, but in the end Chemical Hearts is never as essential or as definitive as it clearly thinks it is.

Flickering Myth Rating – Film: ★ ★ / Movie: ★ ★

Chemical Hearts will be available on Amazon Prime Video from August 21st.

Alex Moreland is a freelance writer and television critic; you can follow him on Twitter here, or check out his website here.