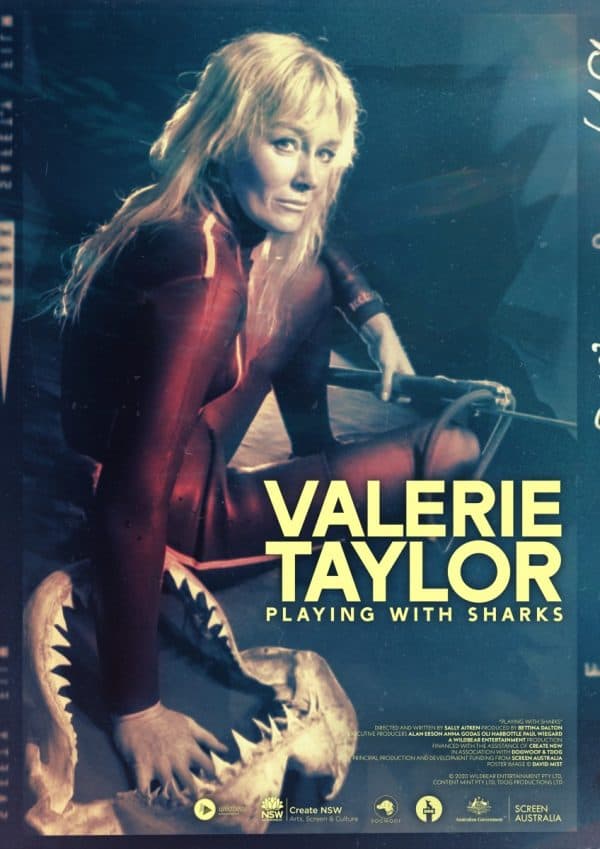

Playing with Sharks, 2021.

Written and Directed by Sally Aitken.

Featuring Valerie Taylor.

SYNOPSIS:

Valerie Taylor is a shark fanatic and an Australian icon – a marine maverick who forged her way as a fearless diver, cinematographer and conservationist. She filmed the real sharks for Jaws and famously wore a chainmail suit, using herself as shark bait, changing our scientific understanding of sharks forever.

You need only turn on the news to see how even the most shoddily presented piece of information can change the tide of public opinion if it plays to deep-seated fears and exploits easy emotion. With passion and insight, filmmaker Sally Aitken explores the ill-informed mythopoeia surrounding sharks, and the intrepid woman who has devoted her life to re-shaping public opinion.

That woman is Valerie Taylor, an Australian diver, oceanic photographer, and marine conservationist who, at 85 years of age, still strives to change the prevailing narrative that sharks represent a threat to human beings, likening them instead to dogs.

But Taylor’s quest isn’t merely one born from her own love of the ocean and everything in it; it’s also an act of contrition, given that she herself was once part of a culture that encouraged shark hunting, and she even filmed the underwater Great White Shark scenes for Steven Spielberg’s perception-shifting Jaws.

But first, Aitken briefly traces how Taylor fell in love with the ocean as a child in the 1950s, and went on to become one of the few prominent women in the spearfishing community. She wanted a life beyond what was expected or “allowed” of women in the era, and evidently hasn’t let up one bit over the decades.

Indeed, Taylor is a fascinating subject not only for the life she has lived but the vast swath of social change she has experienced. In one stirring scene, Taylor admits that she in fact killed a shark in her youth, the resulting regret of which spurred her to become a conservationist, while speaking of a generation who, in her words, thought the ocean was an infinite resource.

And so, she opted to shoot sharks with her camera instead of a speargun. Yet the cruel irony is that Taylor may have been party to more damage as a member of the media corps than she ever was as a spearfisher. After all, what do news networks love more than footage of “dangerous” animals? Apparently customers were even more keen if Taylor, a strikingly beautiful woman in her youth, was shot in implied peril alongside the animals.

This adds a whole other stratum to the doc, that Taylor and her late husband Ron were somewhat complicit in this culture of fearmongering. The pair worked on a number of documentary films throughout the early ’70s which at least aided the general public’s understanding of sharks, though the major turning point for social perception was Jaws, both the novel and script for which were written by Taylor’s own friend, the late Peter Benchley.

The rest, as they say, is history. The Taylors filmed the shark with a dwarf actor and half-size sets to ensure the Great White looked 25-feet tall, and the resulting stratospheric success was beyond anyone’s expectations. As Hollywood’s inaugural blockbuster, Jaws held the public consciousness in its grip, leading to wild hysteria about the ocean being unsafe, and most upsettingly, causing some to actually hunt sharks. It’s a testament, ultimately, to the power of cinema as inadvertent propaganda, the fallout startling enough that Benchley later regretted writing the book altogether.

Though the Taylors did return to shoot Jaws 2 in 1978 – a fact curiously elided here – Valerie did develop a spiritual need, a responsibility even, to change perceptions and present sharks as more than a bloodthirsty monolith.

Through the early ’80s, Taylor famously conducted a series of experiments while wearing a chainmail suit and wrapped in bait, seeking to prove that sharks pose little threat to humans without provocation, and also that the crush power of their bites has been vastly overstated. Incredibly, even National Geographic’s own panel of experts initially dubbed the findings a hoax before seeing the light.

50 years on, has Taylor succeeded? The answer is complicated; your average person is still fearful of sharks, unaided by a pop-culture landscape that’s done little to engender more sympathetic depictions (The Meg, anyone?). After all, the uphill struggle against human ignorance – something that feels more relevant now than ever – is strong.

But Taylor has taken enormous strides to increase the protection of sharks, 100 million per year of which are hunted for shark fin soup alone, and in an ironic twist, the area where she filmed Jaws is now a marine preservation site.

Though Aitken’s film could certainly have gone deeper (pardon the pun) in examining the cultural depiction of sharks and our continued response to them, her focal subject is rendered in a compelling combination of charm and regret. She may struggle to get into a wet suit today, but she’s still got a spunky spirit, and as she herself pithily remarks, will probably be diving in a wheelchair someday.

Sally Aitken’s film persuasively dissects some of the more harmful and widespread myths surrounding sharks, even if rewiring public opinion still has a long way to go.

Flickering Myth Rating – Film: ★ ★ ★ ★ / Movie: ★ ★ ★

Shaun Munro – Follow me on Twitter for more film rambling.