Following the passing of Jerry Lewis, Tom Jolliffe revisits The King of Comedy…

With the saddening news of Jerry Lewis departing us a few days ago, it bought to mind not only his fine cinematic outputs as a leading comedic star in the 50’s and 60’s (including classics such as The Nutty Professor and The Bellboy) but also his role in the oft overlooked Martin Scorsese classic, The King of Comedy. Often cast along with Dean Martin in his earlier career, Lewis would later step out of Martin’s shadow and forge a career as a leading man. Though as many will know, as his popularity in the US waned, he picked up more fans in Europe (particularly France). His brand of physical clowning translated well across the world. In fact his films would later become popular across Asia too given his visual comedy was universally appreciated.

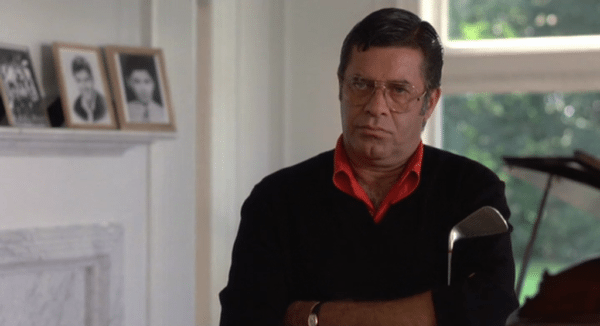

Whilst Lewis may have retrodden too much similar ground as his career began to peter out, he still retained a willing fan base. By the time Scorsese cast him (as essentially a meaner version of himself) in The King of Comedy, Lewis had slowed right down to virtual semi-retirement. After a gap of 11 years, he wrote and directed Hardly Working. Panned by critics upon its release it was a box office success, but Lewis stepped away from the limelight again, before Scorsese came calling another two years later.

The King of Comedy not only marked a change of pace for Scorsese, but it did the same for Robert De Niro. Whilst it’s not overtly comedic, it’s certainly got a line of easy humour and charm running parallel with the darker aspects. It’s a black comedy, which is interesting, complex and with plenty of room for analysis and interpretation. This almost deals, in a more darkly comic manner, with some of the same issues in Scorsese’s iconic masterpiece, Taxi Driver. A protagonist who has a distorted sense of reality that ultimately clouds their sense of right and wrong. If Taxi Driver is the darker, grittier take, King of Comedy delves into a more fantastical, oddly charming story.

As Rupert Pupkin, De Niro portrays an obsessive aspiring comedian and autograph hound who worships Jerry Langford (Lewis). Langford represents everything Pupkin aspires to be. A comedian, a talk show host and someone who commands attention. It soon becomes apparent that Pupkin’s intense fantasies often overlap with reality. As the film progresses and Pupkin’s already fractured mental state deteriorates further, we still cannot help but root for him, such is the charm with which De Niro plays the role. Despite the darker aspects of the film and character, there’s a real lightness to De Niro, of which we’d not seen of him (at the point).

De Niro is ably supported by Sandra Bernhard (as Masha) a fellow Langford obsessive, who simply wants the change to make Jerry fall for her. Both Pupkin and Masha plough headlong into their fantasist ideas with little forethought for reality, logic or common sense. At the time Lewis was long past being a crowd pleasing name. His popularity overseas rested largely on his older films. As an actor he’d often been dismissed as a clown, but under the direction of Scorsese he gives a great performance. He falls into the hands of two slightly deranged oddballs, but Lewis as Langford is dismissive and a little unlikeable. There’s something a little slimy about the guy. He’s a darker version of Lewis, and Langford is all about self-importance and self-preservation.

The film was largely overlooked in awards season. It did receive BAFTA nominations for De Niro, Scorsese, Lewis and Thelma Schoonmaker (Marty’s long term editor) as well as a BAFTA win for Paul Zimmerman’s exceptional screenplay. It has aged incredibly well and is original. Much like After Hours it remains a middle 80’s, overlooked gem in Scorsese’s CV. It looks fantastic. The cinematography and production and set design, all engrossing. Pupkin’s abode is particularly evocative and contributes to that distortion of reality. Not only within the character but also as far as the viewer goes as we must decipher just what is real and what is a figment of Pupkin’s over-active imagination. American Psycho, some 17 years later would cover some similar ground with a likened mix of dark humour and paranoid schizophrenia. American Psycho notched up the violence but took a blunt look at 80’s corporate greed and materialism whereas The King of Comedy is more protagonist focused and within a fantasy realm.

Scorsese was thoroughly in his pomp here. It’s odd to consider a decade like this as somewhat forgettable for him. That would be slightly more true to say of Coppola perhaps (though Rumble Fish and The Outsiders are underrated). The decade was bookended with his two most universally lauded perhaps, with Raging Bull and Goodfellas, yet in between them, though inconsistent, remains some fine work. The Last Temptation of Christ was engrossing, engaging and thought provoking, if difficult to enthusiastically raise your thumb up for. The Color of Money may have been somewhat routine but Paul Newman was fantastic.

Cinephiles of a younger generation, and indeed older, may gradually tick off must see classics over the years. Casablanca: check. The Godfather: check. Etc. This is one of those films that will get overlooked, particularly when the director’s CV includes so many bonafide iconic masterpieces, but The King of Comedy may well be his most underrated. The same goes for De Niro’s performance, and indeed that of the late, great, Jerry Lewis in a role that really showed a different side to him at the time.

Tom Jolliffe