Filmworker, 2017.

Directed by Tony Zierra.

Featuring Leon Vitali, Stanley Kubrick, Matthew Modine, Ryan O’Neal, Danny Lloyd, R. Lee Ermey, Stellan Skarsgård.

SYNOPSIS:

Filmworker charts the multiple decades that Leon Vitali spent as the jack-of-all-trades assistant to famously demanding film director Stanley Kubrick. It’s a glimpse into the ways Kubrick worked that is both fascinating and heartbreaking, especially in the ways the director, and then his estate after his death, treated someone who was unwaveringly loyal. The lone bonus feature is a Q&A with Vitali and director Tony Ziera.

Behind every Hollywood legend there’s usually at least one assistant who helps keep that person’s world turning in countless unsung ways. In the case of famous film director Stanley Kubrick, there was Leon Vitali, who was different from other assistants in film lore because he cut short a promising acting career to take on a thankless role.

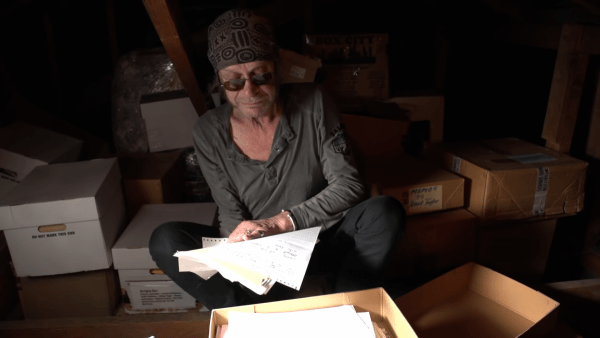

He was also different because he did so much more than keep the trains running on time, so to speak. When needed, Vitali served as casting director, editor, film archivist and restorationist, and more. He even stepped in to play a masked role in Kubrick’s final film, Eyes Wide Shut, which, of course, didn’t allow him to shirk his other duties even as he was filming his lines over and over again, as the director famously liked to do.

Director Tony Zierra’s documentary about Vitali, Filmworker, takes its name from the occupation Vitali put on various forms. It was something he came up with, he says, because he saw himself simply as someone who works in film. He acted in many British TV shows and movies before being cast as Lord Bullingdon in the 1975 Kubrick film Barry Lyndon. While on the Lyndon set, he was fascinated by how the director was involved in every aspect of the production and how every crew member around him had a key role to play.

That fascination led him to essentially creating a job for himself with Kubrick, who, as Vitali tells it, was masterful at coming across as benign and gentle at first before later revealing his controlling and demanding side. In that context, Vitali notes that Kubrick loved to play chess, but I don’t know if that’s a masterful relationship move as much as someone who wants to hide their distorted personality until the other person is in too deep. Kubrick was brilliant, but he was also abusive – I’ve long felt that his infamous obsession with shooting even the most mundane moments over and over wasn’t so much about perfectionism as it was about a sadistic tendency to see how far he could push people.

In Vitali’s case, I don’t think there was ever a notion that he was in too deep. He seemed to revel in his relationship with Kubrick, enjoying the fact that he worked long hours seven days a week to serve all of the director’s whims and needs. The only times cracks seem to appear in that happy façade are when he relates moments where he’s perhaps considering that Kubrick went too far – such as when he horribly mistreated Vitali on Christmas Eve, gave him a present and sent him home, and then started calling him on Christmas Day to hound him about many tasks that needed to be done.

When Kubrick died, Vitali seemed to be cast aside by people closest to the director who took over his estate. It’s telling, for example, that this documentary doesn’t feature interviews with Kubrick’s widow Christiane and her brother Jan Harlan, who executive produced several of the director’s movies and was known as his right-hand man. Vitali was constantly at Kubrick’s home when he wasn’t on movie sets or doing prep work for movies such as location scouting and casting, so obviously the two of them would have been around him quite a bit.

It’s clear that Vitali was stung by being excluded after Kubrick’s death, and that feeling is echoed by Warner Bros. executives and others who were interviewed for Filmworker. The actor Matthew Modine, who encountered Vitali while filming Full Metal Jacket, even goes so far as to say that he felt bad by the way Vitali was treated on that set and wanted to save him from Kubrick.

Despite all of the abuse, Vitali has remained devoted to Kubrick for the more than two decades after the director’s death, even going so far as to show people around an exhibit about Kubrick that he wasn’t involved in creating. However, a postscript notes that the Kubrick estate brought him in to work as a consultant for a 4K version of 2001: A Space Odyssey and to create an archive of the director’s film elements. Hopefully these are paid gigs, since the documentary notes toward the end that Vitali had been doing unpaid work for the Kubrick estate.

The lone bonus feature on this Blu-ray disc is an 11-minute Q&A between Vitali and Zierra, which I assume was conducted after a screening of the film. Speaking of Kubrick, Vitali says “all artists are disobedient,” which I suppose is his way of rationalizing the way he was treated. Zierra discusses how the film came about: it was meant to be a different kind of documentary about Kubrick, but it morphed into Filmworker when he encountered Vitali.

Flickering Myth Rating – Film: ★★★★ / Movie: ★★★★

Brad Cook