Tom Jolliffe on the art of confusing an audience and getting praised for it….

Cinema and TV is full of fine margins. There’s a real artistry in how a film (or show) can manipulate the viewer. As a viewer you are taken on a journey. Sometimes said journey is simple. A to B to C. A simple quest, an expected ending. When Jean-Claude Van Damme starts his journey in the Kumite, we know how the film will end. We usually know the beats as they happen. What about when you sit through a David Lynch film or TV show? Perhaps to some, that journey, with a vague route through from beginning to end, is frustrating. In the end though, Lynch gathers up fans, cult appeal and enthralls audiences, even when he agitates them.

When we watch a film or TV show, we must give ourselves over to what is happening. There’s a skill as a film-maker in keeping your viewer at arms length, but keeping them interested. The water cooler TV event of the moment in the UK, Line of Duty has just finished its 6th season. We’ve been strung along through a series of exposition heavy interrogation scenes, perpetual red herrings and a rotation of bent coppers become a central focus each series (beginning with Lennie James, ending with Kelly MacDonald, with everyone in between). Without giving too much away, some things have been answered whilst others remain open ended, leading to the potential of another series which could conceivably carry on the through-line, whilst evolving into a new thread too. Whilst finale syndrome inevitably leads to contention (and the finale of season 6 has been greeted with mixed reviews), the whole 10 year journey, despite being frustrating at times, has been enjoyable. Frustrating can be good in moderation, if we’re given enough challenge and enough interest to come back for more. That said, I’ve spent 6 seasons of this being constantly asked by my wife, “Who’s this? Why did they do that? What happened?” Truth is, half the time, I’ve no idea myself, but up until the meandering final episode, I’ve enjoyed the ride.

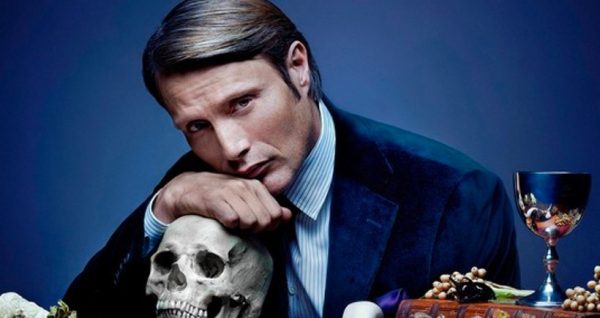

Sticking with TV, one show which began brilliantly but petered off was Hannibal. Sure, Mads Mikkelsen (as Lecter) was superb throughout, with a great recurring mental joust with Hugh Dancy (as Will Graham), but after the second season, a third got bogged down in back story, repetition and unnecessary timeline shifts, as well as overstuffed with the metaphysical. The show went from having those elements of alluring confusion, to being annoyingly confusing. When you’re confusing but not that interesting, then there is a problem. Many bemoaned the shows cancellation but I’m not too surprised it was canned either.

One director, Lynch aside, renowned for puzzling audiences with head scratching concepts, or narrative structure, is Chris Nolan. In actuality the through-lines of his stories are deceptively simple, housed inside a high brow, high concept package. Take Inception. The film sees a group of specialists seeking to implant an idea into someone’s subconscious. You can explain that in a single line, but the reality of how this is done descends into an exposition heavy tale of dreams within dreams (with dreams…within…). Nolan toys with the viewer by throwing in a protagonist (Cobb, played by Leonardo Di Caprio) who is always at odds with reality. As our lead, we have someone unreliable, though in the shape of Elliot Page and Joseph Gordon Levitt we have two kind of dull characters who exist to explain things to a degree that the audience can almost catch up to Nolan. Tom Hardy exists to do likewise, but has more room to imbue his character with some personality.

When I talk about the fine lines in cinema, Nolan is a good example. In Inception, a film widely considered a modern day classic of blockbuster cinema, he maintains a film that is thoroughly engaging and loaded with eye blistering spectacle. That we could easily get bogged down in weighty ideas and even weightier exposition is the gamble he takes. He treads that line brilliantly, and the legacy of Inception is there to see (though I do find it a tad overrated). By contrast, Tenet divided audiences far more. He crossed that line. There were similar themes in what some describe as a kind of spiritual successor, but if Inception pushed comprehensibility to the max, Tenet shattered it. It had the same faux pas’ that screenwriters are often warned against (heavy exposition, confused ideas), but wasn’t as interesting. It wasn’t as alluring. I feel no pressing need to revisit and delve into the hidden caveats of Tenet (nor were the set pieces as astounding).

In arthouse, form and structure can be discarded entirely, in favour of creating a purely emotional reaction from the audience. It can become an experience to feel, to let us embellish meaning with our own preconceptions. You might see this in a film like The Color of Pomegranates for example, and most certainly in most of Andrei Tarkovsky’s work. Often as absorbing and rewarding as they are challenging and confusing, works like Stalker play with the preconceived expectations of narrative structure and clarity of meaning. Everything a writer is told to adhere to in textbooks, is thrown out the window by the Art-house form. Tarkovsky’s most elusive creation, also proved to be his most visually dazzling (which given his oeuvre, is saying something). Whilst The Mirror offered a personal reflection of Tarkovsky’s own experiences, it was also organic, fluid and dreamlike, melding memories with dreams and visions, as the protagonist (who is largely unseen) recounts moments in his life.

David Lynch’s approach to films like Mulholland Drive or with Twin Peaks was to create a vivid universe where random events could intertwine and have profound meaning or no meaning. Moments in Lynch films become head scratching, but enthralling. David Cronenberg likewise had that gift in some of his films. Both Lynch and Cronenberg have had more successful films than others as far as bewildering an audience willing to take it. If Videodrome became a cult classic baring endless repetition, the complex but doubly confusing Spider did not (though I do think it’s vastly underrated). In the same way, Lost Highway proved too frustrating for audiences, even by Lynch standards and Mulholland, a few years later would be the one that marked Lynch’s return to oddball form (with the unusually ‘normal’ Straight Story in the middle).

What are the most confusing films you’ve seen? Which did you enjoy? Which were just too confusing for their own good? Let us know on our social channels @flickeringmyth.

Tom Jolliffe is an award winning screenwriter and passionate cinephile. He has a number of films out on DVD/VOD around the world and several releases due out in 2021/2022, including, Renegades (Lee Majors, Danny Trejo, Michael Pare, Tiny Lister, Patsy Kensit, Ian Ogilvy and Billy Murray), Crackdown, When Darkness Falls and War of The Worlds: The Attack (Vincent Regan). Find more info at the best personal site you’ll ever see here.