Tom Jolliffe looks at Dolph Lundgren’s work behind the camera as a director…

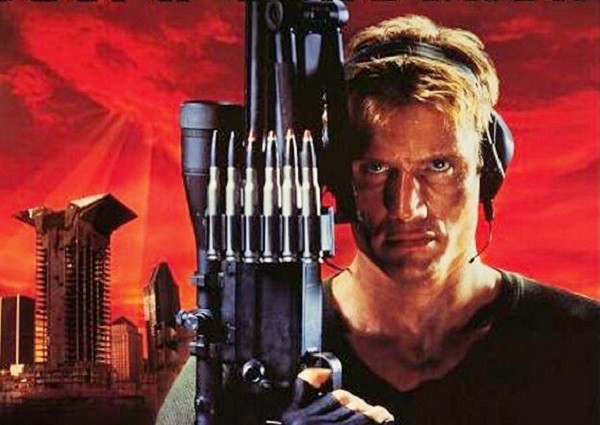

Dolph Lundgren is an action icon. For many fans his most enduring images are that of Ivan Drago, one of the most iconic villains of the 80’s from Rocky IV, or as He-Man in Masters of the Universe. Beyond that he’s been the Punisher before anyone else was on screen, and he’s been a Universal Soldier as well as starring in an array of cult favourites like Dark Angel, Showdown in Little Tokyo and Red Scorpion. Dolph has always been something of a surprise package. To the aficionado it’s long been known that he has a Masters degree in chemical engineering and was accepted into M.I.T, before a certain Grace Jones (who met Dolph as a bouncer in Sydney) introduced him to the club, celebrity, and art and culture scene (including Andy Warhol no less). Additionally, Lundgren, much like his ‘surprise’ academic background has been repeated almost ad nauseum as a new discovery, is also a black belt in Karate and former European kickboxing champion.

Several ‘comebacks’ over the last decade plus, including The Expendables series, Creed II and Aquaman 1 and 2 have brought the press back to the door of an actor who had laboured in straight to video land for some years. So it’s natural that budding journalists (during articles or interviews) dig out these facts again and again as if they’re the first to do it. The point is though, Dolph is more complex than the action man image he’s often known to portray on screen. Much like many of his muscular contemporaries, he’s perhaps oft dismissed as a meat head which couldn’t be further from the truth.

Lundgren has long held ambitions beyond simply appearing on screen in occasionally interchangeable run and gun action films. It began early, even if his acting career had started almost as an afterthought. It’s a long way from the lab to the film set after all, by way of nightclub bouncer (alongside Chazz Palminteri). He’d not long set his sights on acting when he found himself thrust into the limelight by Stallone. It also wasn’t long after Rocky IV that Lundgren began to take things very seriously, with ambitions to produce and develop more indie, personal projects. He’d planned to write and produce a film about the nightclub scene in Sydney, which would undoubtedly have drawn upon his own experiences. It didn’t come to fruition. His first foray into producing came with something of an oddity, Pentathlon. One of the less eye-catching or popular Olympic sports (despite an interesting mixture of events, running, swimming, equestrian, shooting and fencing), it was also a film slightly hamstrung by a low budget and TV movie aesthetic, as well as a very Lundgren-esque action subplot that involves foiling his former coach’s new Neo-Nazi terrorist movement. In time it’s picked up more appreciation for just how uniquely madcap it is. Part Rocky, Chariots of Fire, by way of Marathon Man, as if made for TV, with David Soul magnificently hammy as the villain. Not the most auspicious debut behind camera though.

SEE ALSO: Pentathlon: The Best Olympics Movie You Never Saw

Lundgren didn’t have a particular identifying trait beyond his size, a calling card. His work as a villain tended to be his most eye catching and successful early on, whilst he was often somewhat (perhaps surprisingly) reluctant to use his martial arts too much. Whilst Jean-Claude Van Damme did the balletic slow-mo thing and Steven Seagal did the Aikido thing, Dolph had no thing, but perhaps interestingly, he first showed an eye to branch out. It never quite worked, be it Pentathlon, or espionage thriller Cover Up, oddly artistic, philosophical actioner Silent Trigger, or Euro-Thriller throwback, The Shooter. He was trying to find some leverage as an adaptable actor. Some choices were questionable, others plagued by bad luck. He’s got a long history with production and distribution companies caving just prior to releasing his films, or films being placed up against an all consuming juggernaut, which partially explains why big screen box office draw has always eluded his solo work. Additionally, try as one might to branch out, occasionally you can only go half in to an idea that subverts the ‘Lundgren’ expectation. They still require those formulaic elements and a minimum of fisticuffs, often crowbarred into the original ideas.

SEE ALSO: Silent Trigger: Straight-to-Video Arthouse Action

Step forward to 2004 and it seemed those aspirations were in the past. Not merely as an actor, where choices had now been confined to the most basic expectation with generic heroes and routine action films, but behind camera. There’d even been retirement rumours. However, through a twist of fate a few weeks prior to shooting The Defender with Sidney J. Furie directing, the filmmaker became ill. Furie recommended Dolph to take up the reigns and he did. The Defender was a fairly simple siege movie which sees a team of military bodyguards looking after a mystery client, besieged by terrorists looking to take out said target in a remote Romanian hotel. For what it was, it was well delivered, etching out side characters to enough degree that it had some impact when they are taken out. Aided by Maxime Alexandre (High Tension, The Hills Have Eyes) on DP duties and a non-stop final third, Lundgren had made his best film in years. If his career had slumped to a level where precision, creativity and artistry were a rare occurrence (or directors where tied down), then maybe there was something in taking control himself.

Dolph’s sophomore directing gig, like his first, was a recognisable trope. An idea that Lundgren was well versed in and fans would buy into. His family is killed, he seeks revenge. The Mechanik plays like a Neo-Western, bringing with it the chance to tap into Lundgren’s key source of inspiration as a film-maker, Clint Eastwood. As with all his directorial works since, Lundgren also stars (which is effectively the trade off required by the financial backers). Like The Defender, it had a skill in the more reflective moments of drama that were often completely overlooked in the films he’d been doing around the time. Lundgren didn’t just want to make good action, he wanted you to care. The late Ben Cross, who becomes something of an unlikely partner to the vengeful protagonist adds some gravitas, and sensibly Lundgren retains stoicism to the more expressive Cross. Whilst Dolph has certainly improved as an actor, in actuality showing an ability to make a good character actor, the pressure of dual roles in front and behind, lend itself to sharing some of that on screen responsibility with a dramatic stalwart like Cross. Lundgren got every beat right in what was a nice little 70’s inspired throwback, but perhaps some of the most impressive scenes exist in moments before the big final standoff. Nikolai (Lundgren) and his band of mercs hold up in a remote rural village, treated to some hospitality with time to reflect on what has been and what is coming. The fact is, a quiet, thoughtful scene like this is almost never found in straight to video action, but it makes the picture.

So far so good, but now Lundgren would find things more difficult. Studio politics, tight budgets and schedules and many other factors effected his ability to get films made how he wanted. Missionary Man, a modern Western saw Lundgren shooting in Cowboy country as the stranger riding into town for a funeral. The town is under the thumb of mob rule and government corruption, and the family of the deceased have fallen foul of the local enforcers. It’s pure Eastwood, and Lundgren had grander stylistic ideas than the production company could/wanted to deliver. On a tight budget and tighter schedule, the films monochromatic look wasn’t quite as envisioned (and whether the choice to shoot on Super 16 was forced or not, may have been a factor). A cobbled cast of locals weren’t always up to par (though the late August Schellenberg has presence and John Enos III is an impressive, albeit late arriving, villain). Something that might have felt a little more graphic novel, just didn’t quite come off sadly, but again, an underpinning mysticism and ambiguity gives it more repeat value than other DTV rivals of the era.

Elsewhere Dolph had to take some control over the disintegrating production of Diamond Dogs (from director Shimon Dotan), a film which began with promise, and had a more elaborate, Indiana Jones inspired Mongolian adventure script than what was finally delivered. You can almost see through the film where things began falling apart, as twenty minutes in, from having some interesting production design and more assured filming, it all becomes more sparse, vague and hampered by a poor cast outside of the local talent like Nan Yu. Things went better again as Dolph revisited the Die Hard routine he’d successfully navigated in The Defender with Command Performance. It came announced by a wry and eye catching teaser (conceived by Jeremie Damoiseau). Dolph rocking a drum kit, as we pan around and behind him to reveal something…a gun…(because it is Dolph after all). He pulls and shoots. Time to rock and load.

The film proper saw Lundgren as a nomadic drummer, currently hitting sticks for an East European metal band and about to perform second billing to a pop princess at a concert for the Russian premiere. Terrorists take over and the drummer has to save the day. Yes, someone dies by drumstick (as well as guitar). Shot on Super 35, it’s glossy for its budget, albeit hampered by pacing and the constraints of the single setting film. There’s just enough tongue in cheek humour, whilst retaining some humility, to make the film work though, even if there’s the awkwardly forced romance between Lundgren’s aging former biker turned rocker and the young pop starlet. In actuality though, it was one of the better DTV Die Hard riffs of the decade with a good support cast and impressive set pieces (including the staging of the music).

SEE ALSO: Dolph Hard: When Dolph Lundgren Does Die Hard

The next film from Dolph’s short and productive run as director would also end up being his last for 11 years. Icarus (also known as The Killing Machine) was envisioned as a dark neo-noir but was heavily simplified by its release. Lundgren wasn’t happy with the visual look, and certainly not the final cut, for a film that was meant to be a little more complex and slow burning. It was made in that period of digital film where all too often the films ended up looking a little like home movie. The right DP, grading, time and more money would certainly help but those realities don’t often click into place. Certainly the visual approach can be seen in places, particularly through an all too brief and slightly montage reliant opening 10 minutes, which is more predominantly shot at night, but the final result feels almost unfinished. It’s enough to put you off directing, and to some extent it made Lundgren reticent to get back to the role, if circumstances weren’t better.

Which brings us to Castle Falls. A decade of waiting, not without attempts to get back behind the directors chair. Skin Trade was originally conceived as a project Lundgren would direct, before a lengthy development process eventually saw him hand over the reigns to someone else (to focus on starring and producing). Other projects like Wanted Man, Nordic Light and Malevolence also ground to a halt (Wanted Man seemingly back on the cards now). Castle Falls almost came from nowhere. It was a script which Dolph thought was economic in several ways, with potential to be a good project to get back into the chair with. Production began…then it stopped after a day. Yeah, that’s Covid for you. By the time the filming recommenced the production had to deal with the new realities of Covid set procedures (and the costs), as well as a very tight 17 day schedule. Lundgren sensibly sidesteps into a supporting role, and even more sensibly gives the lead role to Scott Adkins. In essence this means he has a star who doesn’t need a lot of doubling, but also with the skill to help create and perform engaging action scenes. As you would expect from an Adkins project, Castle Falls has a number of nicely composed and performed fight sequences with a dynamism that injects the film with energy.

However there’s something even more interesting about the film and it is the signs of development with Dolph the director. There’s a subtle evolution. He’s always had character focus, and even though he might have had to fight for many of those non-action moments, he’s approached the drama as intently as the action. Castle Falls opens with a distinctly Indie feel. It’s almost as much A24-lite, than atypical VOD action fare. Lundgren sketches out these individual characters, willing us to want to engage in their story. Of course the basic premise sees us going into that similar territory of The Defender and Command Performance, the action beats fans demand/expect. Lundgren is almost wilful in back loading the action to the finale. It doesn’t always work, but for the most part it does (the film has been greeted with generally positive reviews, and for the most part 3 star). As a project, he might have set a low bar, but it’s an attainable one, hit with aplomb (you need only compare to Hard Night Falling, one of Lundgren’s previous films which is all but the same basic premise, but nowhere near as good).

Adkins has developed into a solid actor, imbuing Mike with vulnerability, and Lundgren is also focused as an on screen performer here, adding plenty of pathos to Ericson, the prison guard with financial woes and a daughter in dire need of cancer treatment. They’re basic tropes, but the sincerity with which Lundgren et al deliver the drama is what carries the film through it’s more action orientated back end. In fact the budgetary limitations and slight lack of a big stand out set piece/stunt (beyond the intimate fights), are less problematic, because we have some investment in those characters. Importantly it shows potential that Lundgren could branch away from generic action ideas as a director, and do something even more character focused. Many of his contemporaries have tried their hand at directing and quickly found a brick wall, but much like Sylvester Stallone, Lundgren’s hidden depths have helped him in becoming a solid director, and certainly one who might deserve a backing outside his tried and tested genre.

Tom Jolliffe is an award winning screenwriter and passionate cinephile. He has a number of films out on DVD/VOD around the world and several releases due out in 2021/2022, including, Renegades (Lee Majors, Danny Trejo, Michael Pare, Tiny Lister, Nick Moran, Patsy Kensit, Ian Ogilvy and Billy Murray), Crackdown, When Darkness Falls and War of The Worlds: The Attack (Vincent Regan). Find more info at the best personal site you’ll ever see here.