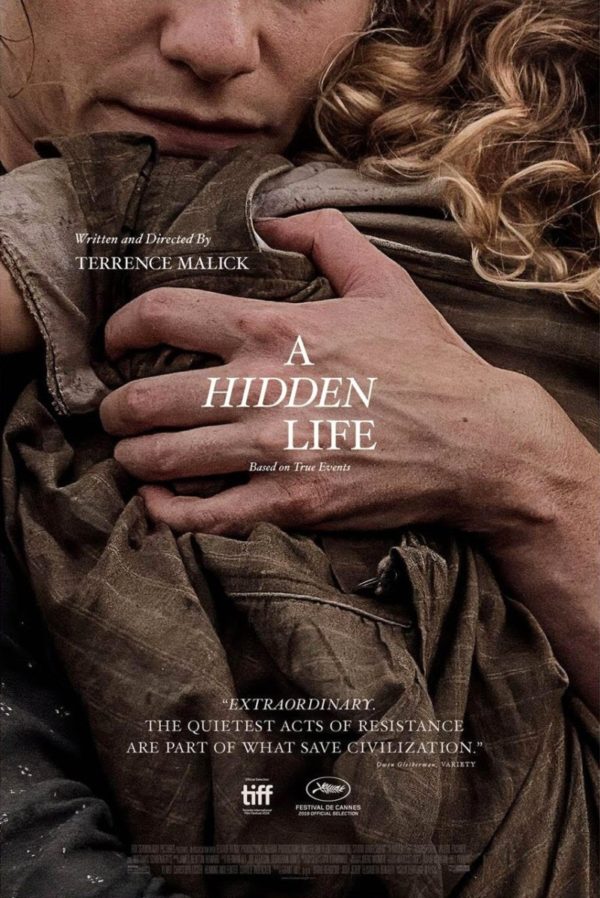

A Hidden Life, 2019.

Written and directed by Terrence Malick.

Starring August Diehl, Valerie Pachner, Matthias Schoenaerts, Michael Nyqvist, and Bruno Ganz.

SYNOPSIS:

Austrian farmer Franz Jägerstätter faces the threat of execution for refusing to fight for the Nazis during World War II.

After spending years out in the experimental doldrums to the extent of borderline self-parody, Terrence Malick returns to something approaching terra firma with this affecting historical drama. However, with its impact-blunting 173-minute runtime, it’s hardly free from the auteur’s typical indulgences.

Compared to his more overtly out-there recent films, A Hidden Life might seem like a relatively conventional effort at first glance, yet it’s ultimately a canny compromise between Malick’s various filmmaking modes and interests.

The set-up, following the imprisonment of conscientious objector Franz Jägerstätter (August Diehl) after he refuses to swear loyalty to Adolf Hitler during World War II, might seem like a fully-fledged return to card-carrying A-to-Z narrativity for the filmmaker. But more than anything, this is simply another lens through which Malick continues his near-five-decade quest to find meaning in human existence (specifically in this case, cruelty).

Malick fuses his exploratory approach to character and story with his penchant for poetic observationalism in a movie that’s by turns bold and bloated, and sure to leave his fans rapt while his ardent cynics again frustrated.

Indeed, this is the closest thing to a strict narrative film the director has made in years, even if many of his flowery affectations still persist; the breathy, portentous voiceovers are back and don’t want much for subtlety, even if well-read by Diehl and Valerie Pachner (who plays Franz’s wife, Fani). The whole is far more pointed and less opaque, however, than the likes of To the Wonder, offering up a searing meditation on faith, both that held for religious institutions and for people.

At its core, A Hidden Life is a haunting examination of how people face up to a significant existential threat, either by standing defiant or, more likely, keeping their head down and getting on. Malick explores the level of spiritual compromise people will be prepared to accept in order to keep living, memorably illuminated when Franz’s wife tells him, “You can’t change the world. The world’s stronger.”

Once Franz refuses to swear fealty to Hitler, the film’s unexpected contemporary parallels soon begin to crystalise, and a surface-deep reading of the film could call it a rallying cry to stand up to Nazis in our present, which just might make this the most culturally significant and relevant project Malick has undertaken in years.

But even as the director persuasively restrains himself and deepens both his characters and themes in the process, this film does feel most of its near-three-hours. One suspects, however, that Malick doesn’t so much expect the audience to be intently glued to the screen in every single moment, but simply soak in the whole as a gorgeous, ambling tapestry.

A Hidden Life is thoroughly enlivened by a wonderfully understated performance from lead Diehl, best known to English-speaking audiences for his slimeball Nazi role in Inglourious Basterds, and his endlessly expressive face conveys so much inner turmoil even when he isn’t asked to speak. Pachner is also very effective as his spouse, who despite offering no such formal renouncement of the Führer, is viewed as a pariah in her homestead for her husband’s defiance.

Like most Malick movies, this thing spent a good while in the oven, with the project completing principal photography over three years ago, long enough for two of its actors who appear in minor roles – the brilliant Michael Nyqvist and inimitable Bruno Ganz – to have since passed away. Supporting roles are typically fleeting, however, with Malick pulling his focus tight on Franz and Fani in alternating passages once Franz is taken to jail for his actions.

Surprising no-one, this is a beautiful-looking movie. The mesmerising opening shot of Franz ploughing a field with the Austrian Alps unfolding in the background is one of the most painterly visuals you’re likely to see all year, confirming from the jump that, yes, the Alps are present enough to basically be a character in their own right.

Malick’s love of wide angle lens coverage and roving cameras takes some getting used to, as it always does, but it also gives the film a unique, distinguished look, while avoiding the more offputting experimental lenses deployed in Malick’s last few films. A brief foray into first-person perspective when Franz receives a kicking in prison, however, flatly doesn’t work. Editing for both picture and sound adheres slavishly to his typical dreamlike approach, yet in large part due to the real-world heft of the material, it’s a conceit that really works.

Sound mixing is meanwhile first-rate, and Malick makes the interesting decision to leave much of the incidental German dialogue unsubtitled, because as he has succinctly proven in every single film he’s ever made, he’s far more concerned with feeling than exactitude. James Newton Howard’s musical score also does a fantastic job underlining the emotional agency of Malick’s images.

Like many of the director’s best films it trades storytelling subtlety for heart-on-sleeve drama, and proves thoroughly gripping in all of its broad emotional candour, leading up to a gut-wrenching third act that’s among the most soul-crushing work – and surely the most tense – he’s ever put to film. When A Hidden Life ended, I felt both anxious dread and hopeful uplift, as it reminded me of how little truly has changed since WWII, while providing a rousing, triumphant final quote from George Eliot which circles back to the film’s title.

There is a great two-hour film which could be chipped away from this nevertheless very good three-hour one. Though some of the more dawdling scenes depicting Franz’s imprisonment seem especially drawn out, one suspects the aim is to heighten our empathy with Franz’s own slogging it out.

If a more impactful movie is entombed within its excessive three-hour runtime, the editorially undisciplined A Hidden Life is still Terrence Malick’s most affecting and timely movie since The Tree of Life.

Flickering Myth Rating – Film: ★ ★ ★ ★ / Movie: ★ ★ ★

Shaun Munro – Follow me on Twitter for more film rambling.