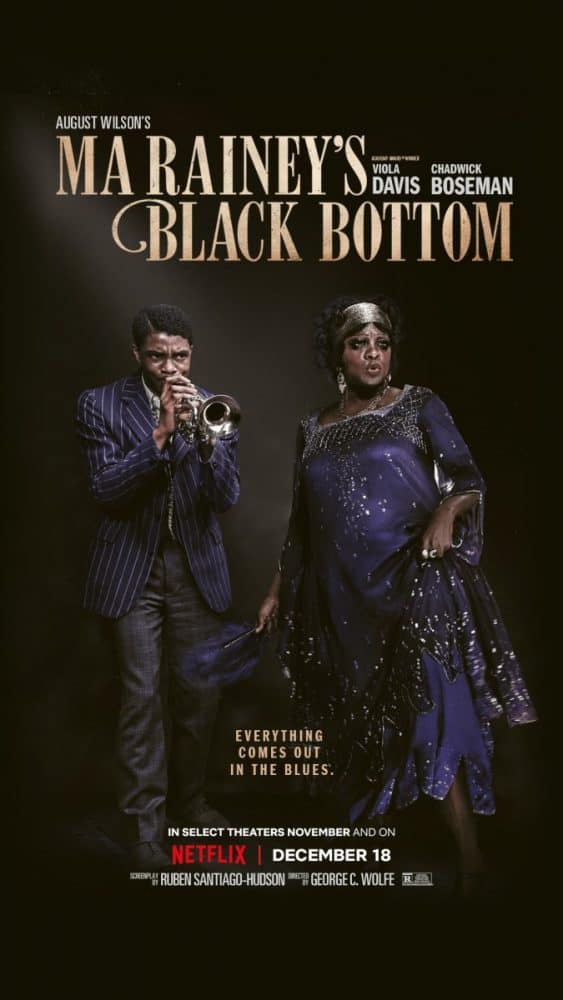

Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, 2020.

Directed by George C. Wolfe.

Starring Viola Davis, Chadwick Boseman, Glynn Turman, Colman Domingo, Jeremy Shamos, Taylour Paige, Jonny Coyne, Michael Potts, and Dusan Brown.

SYNOPSIS:

Chicago, 1927. A recording session. Tensions rise between Ma Rainey, her ambitious horn player, and the white management determined to control the uncontrollable “Mother of the Blues”.

In any other year under any other circumstance, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom would be yet another well-crafted, brilliantly acted adaptation of a Tony Award-winning play inevitably gunning for Oscars.

But it’s 2020, and while George C. Wolfe’s (The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks) drama was wrapping up post-production in August, star Chadwick Boseman passed away unexpectedly from a cancer battle he chose to keep private.

Were this a lesser film, Boseman’s death would hang over it like a dark cloud, yet because it’s such a ferocious, persuasively performed piece of work, and such an unshakably outstanding tribute to the late actor’s talents, it feels more like a celebration than a eulogy.

In 1927 Chicago, a band of musicians twiddle their thumbs waiting for the inimitable “Mother of the Blues,” Ma Rainey (Viola Davis), to arrive at a recording session. In the meantime, jokes are told and tensions eventually arise, centered around the ambitions of trumpeter Levee (Boseman). Levee has given some of Ma Rainey’s signature tunes a re-working for white predilections, at the behest of her manager Irvin (Jeremy Shamos) and album producer Sturdyvant (Jonny Coyne) – who, unsurprisingly, are also white.

The rest of the band – Culter (Colman Domingo), Toledo (Glynn Turman), and Slow Drag (Michael Potts) – take various stances on Levee’s admittedly skilful revisions, which from Levee’s perspective are in service of bolstering his cred in the industry, hoping to release his own self-penned songs in the future.

And then Ma Rainey herself shows up, none-too-pleased that her music is being toyed with by men both black and white. But unlike her band, Ma Rainey has a high degree of pull with her studio benefactors; she knows her worth and isn’t afraid to walk if the required gratitude isn’t shown. This is, in one memorable scene, something as simple as ensuring she’s got a few Cokes on hand to gulp down in the stifling recording studio – and she’ll hold up the session all day, quite rightly, if they don’t comply.

As much as Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom is about music, only a fraction of its lithe 94-minute runtime actually features playing at all, August Wilson’s play focused instead on a dense, witty examination of two primary themes – race and power.

For Levee, he finds himself desperate to settle in a niche where he smiles at the white man and does their bidding, all in the stead of getting his own voice to the masses one day. Ma Rainey, already a commodity in her own right, is acutely aware of how even those who benefit handsomely from her talents perceive her, shrewdly noting they’ve only ever invited her to dinner once – and only to perform for other white acquaintances.

Despite being the title character, Davis’ Ma Rainey has a considerably smaller part than those unfamiliar with the play might expect. This does nothing to diminish the commanding gravitas Davis brings to the part every nanosecond she’s on screen; an elder stateswoman of the Blues who carries a quite literal heft, with Davis donning a fat suit to more convincingly resemble the plus-sized singer.

It is a thoroughly transformative performance, still recognisably Davis and yet, a very different kind of intensity from what audiences are used to seeing from her. For the most part her Ma Rainey almost seems literally intoxicated on her own unflappable insouciance, keen to go to bat and take care of business when even the most ridiculous situations abounds; in the film’s broadest-skewing subplot, insisting that her stuttering nephew Sylvester (Dusan Brown) introduce her on one of the tracks.

Yet as magnetic as Davis is – and, impressively, even performs one of the songs herself – this is a film that belongs in its very soul to Chadwick Boseman, who delivers a performance of such tenacious vivacity it beggars belief that the man was in the throes of a terminal illness. On one hand, Boseman presents Levee as an infectiously charming entertainer, bouncing around the recording session in his gorgeous new shoes and belting out tunes with an enthusiasm as hungry as it is hauntingly desperate.

On the other, Levee is a more complex figure than he first seems, not merely a man cowing to the moneymakers’ demands. A show-stopping mid-film monologue, masterfully wrought by Boseman, details an extremely traumatic incident in Levee’s youth which made him the man he is today; this is just one of many scenes where Boseman is given the floor to thump his chest and drop jaws doing so. Wolfe has the artistic sense to hold the camera firmly on the actor during most of these scenes, capturing them through long, handheld takes.

There has unsurprisingly been much Oscar hype for Boseman’s performance, and while it’s absolutely an unfair weight of expectation to place upon any movie or single piece of acting work, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom does feature several scenes which can rank among the very finest of the actor’s tragically curtailed career.

And though the film concludes with a devastating final scene tinged with the faintest veneer of pitch black comedy, its true climactic melancholy is that it places a premature capper on a career that felt like it was just getting started. If that aching sadness hasn’t already settled in by the time the credits roll, the final dedication to Boseman – “in celebration of his artistry and talent” – will absolutely hammer it home.

A dense, poignant, and often painful love letter to black music, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom serves as a stunning – and undeniably bittersweet – showcase for Chadwick Boseman’s singular talents.

Flickering Myth Rating – Film: ★ ★ ★ ★ / Movie: ★ ★ ★ ★

Shaun Munro – Follow me on Twitter for more film rambling.