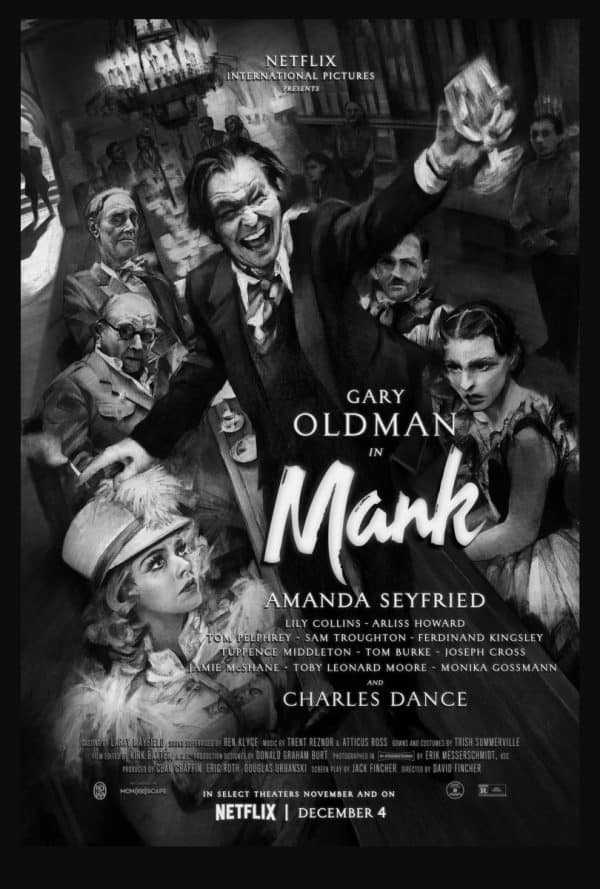

Mank, 2020.

Directed by David Fincher.

Starring Gary Oldman, Amanda Seyfried, Charles Dance, Lily Collins, Tuppence Middleton, and Tom Burke.

SYNOPSIS:

1930s Hollywood is reevaluated through the eyes of scathing wit and alcoholic screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz as he races to finish “Citizen Kane.”

In attempting to reconcile alcoholic screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz’s quest to pen Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane in a mere 131 minutes, David Fincher has produced a film quite unlike anything he’s ever made before; a relatively modest work – by his standards, anyway – so often eschewing stylistic brio in favour of foregrounding its spectacular ensemble cast.

In the film’s late 1930s present, Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman) is holed up in a California ranch, nursing a broken leg from a recent car accident while he attempts to put pen to paper on Welles’ film. But Fincher frequently flings us backwards in time to the earlier ’30s, covering pivotal prior moments in Mank’s life, many of which clearly inform his eventual screenplay.

Through MGM bigwig Louis B. Mayer (played here by a terrifically slimy Arliss Howard), Mank meets media mogul William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance), who of course serves as the inspiration for Welles’ ill-fated protagonist Charles Foster Kane.

But perhaps more tellingly, this also brings him into the orbit of Heart’s partner, actress Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried), widely accepted to be the influence behind Kane’s untalented wife Susan Alexander Kane – a claim nevertheless disputed by Welles himself.

And though I call Mank a modest film compared to the splashier proclivities of Fincher’s prior work, it is still a heady and labyrinthine project in its own way. Rather than simply assemble a straight psychodrama about a man’s writer’s block, Fincher – or rather, his late father Jack, who penned the screenplay almost 30 years ago – constructs a far more slippery and cynical film about the dark heart of Hollywood which isn’t nearly as dew-eyed as many will be expecting.

Then again this is Fincher, a storyteller defined by unrestrained nihilism for most of his career, and while Mank may not plumb the grim depths of a Seven or The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, it does paint a lurid picture of an industry exerting a dangerous, discomforting influence upon the real world.

Beyond the fact that sleazeballs like Mayer are keen to fleece their own employees’ wages during periods of weak business, a surprising amount of the film is committed to exploring how influential cinema has been upon political machinations. The Mayer-Hearst pairing speaks for itself, but in more overt terms Mank sits center-stage to witness Hollywood’s firebombing of Democrat Upton Sinclair’s 1934 California gubernatorial campaign, derailed by propaganda-style, anti-Sinclair news reels produced at Mayer’s behest.

It makes for a compelling if at times unwieldy stew, and surrounded by so much mannered ugliness as he is, it’s easy to see why Mank favours a drink or ten. Though a man of great intellect and never one not to launch a loquacious diatribe at his inferiors, he also serves as a perversely fitting guide through this hall of reprobates – perhaps because he’s certainly no saint himself.

While some will understandably take issue with the film’s final verdict on Welles’ contributions to Citizen Kane – that, in fact, he had no real hand in the writing at all – it’s certainly not a film that lionises Mank in any overt way, no matter that Oldman’s performance makes it tough not to see the charming, enervated moxie shining through his calloused exterior.

It’s typically through his exchanges with women – not just Marion but also his secretary Rita (Lily Collins) and his wife “Poor” Sara (Tuppence Middleton) – that Mank’s humanity is best felt, save perhaps for a riotous third act tirade which becomes the film’s de facto show-piece.

Though Oldman loves an excuse to swing for the rafters as much as anyone ever has, this is a performance of remarkable restraint, less a man spitting fire than it is a trained thesp reciting his most beloved Shakespeare. There are outbursts, for sure, but it may be by turns the actor’s most smoothly modulated turn to date, and absolutely one worthy of Academy Award recognition.

He’s backed by a relentlessly skilled ensemble, too; Seyfried brings a quiet dignity to Davies which ensures she’s much more than her porcelain features and perfectly coiffed ‘do might first suggest. Charles Dance is remarkable in an all-too-brief role as Hearst, while Tom Burke is simply chameleonic in a few short but spectacular scenes as Welles, capturing the man’s distinctive vocal register so convincingly I almost thought it was a period recording.

Technicals are meanwhile as robust as typical for Fincher; though he ditches his signature digitally-assisted camerawork, this is still a highly regal piece of filmmaking best exemplified by Erik Messerschmidt’s silky black-and-white cinematography and Donald Graham Burt’s lush production design.

On the aural side, the decision to intentionally tinker with the dialogue mix to make it sound more “of the period” feels uncharacteristically cutesy for Fincher, though Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’ orchestral musical score – composed only with instruments available in the film’s time period – ties the aesthetic package together splendidly.

As much as Mank is an expertly crafted and exceptionally acted drama, it’s tough to say how audiences en masse will respond to it; Kane fans and cineastes will doubtless relish the many Easter eggs and fleeting references throughout, though those with a mere passing familiarity with the era may feel overwhelmed by the sheer density of what’s being presented.

Few are likely to miss the prevailing points – Hollywood and City Hall are adjoining toilets in the same bathroom, Welles didn’t earn his screenplay credit – but having slept on Mank for many days before writing this review, I also find myself feeling bereft of a fully emotionally gratifying arc for Mank – or, really, anyone.

It is a film which does so much right, and yet, seems unlikely to be one I return to with the same enthusiastic reverence I have Fight Club, Zodiac, or The Social Network. Not all films are made to be endlessly revisited, of course, though given the richness of its content, it’s a little odd that this elegantly constructed drama leaves me feeling largely satisfied with a single viewing.

If perhaps a film easier to admire than it is to love, Mank nevertheless re-affirms David Fincher’s eye for exacting filmmaking, aided at all times by a crackerjack cast – especially a brilliantly volcanic Gary Oldman.

Flickering Myth Rating – Film: ★ ★ ★ ★ / Movie: ★ ★ ★ ★

Shaun Munro – Follow me on Twitter for more film rambling.