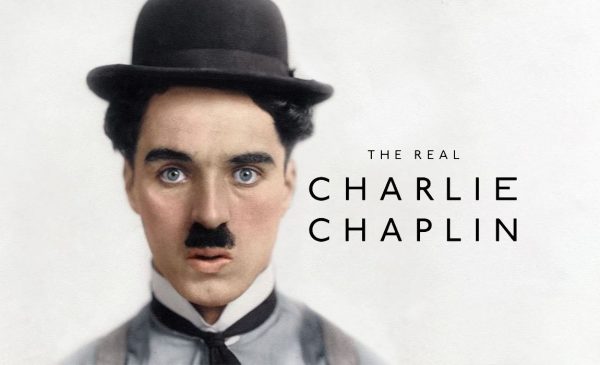

The Real Charlie Chaplin, 2021.

Co-written and directed by Peter Middleton and James Spinney.

SYNOPSIS:

A look at the life and work of Charlie Chaplin in his own words featuring an in-depth interview he gave to Life magazine in 1966.

BAFTA-nominated filmmakers Peter Middleton and James Spinney (Notes on Blindness) return with a less-innovative though absolutely worthy follow-up doc profiling the singular legend of Charlie Chaplin.

Though it isn’t immediately clear how much input, if any, the Chaplin estate had on the end product – possibly tellingly, they are thanked in the end credits – The Real Charlie Chaplin nevertheless seeks to demystify the man, examining the fortuitous circumstances which led to his colossal fame, the influences that defined his art, his anxieties and, crucially, the less-savoury aspects of his private life.

Presented via a nimble collage of first-hand testament from Chaplin’s 1966 interview with Time magazine and the words of those closest to him, Middleton and Spinney trace Chaplin’s impoverished childhood, which became a near-pathologic motivator to his pursuit of fame, and the fast-snowballing success that followed.

Seemingly aware that no feature-length film can satisfactorily cover the entirety of Chaplin’s life and career, the doc instead offers a broad sweep across his most successful works, with accompanying context regarding both the state of Hollywood and his interior life.

If much of the material herein won’t be terribly surprising to even casual Chaplin fans – of course, the Tramp became an emblem of Depression-era America – there are some fascinating sections which consider less-raked-over material. A lengthy consideration of the Tramp’s origins, discussing whether he stole or merely “assembled” the character from myriad influences, is of particular interest.

It’s no secret that Chaplin was also hugely ambivalent about the birth of “talkies,” and while only a small sliver of the film is devoted to this subject, it’s certainly neat to hear Chaplin himself speak with nuance about his feelings. Chaplin praises the power of the human voice but believes that it simply pales in comparison to the virtues of silence, loaded glances, and physical movement.

Given the tendency for history to lionise incredible artists, perhaps this doc’s greatest strength lies in its moments which underline Chaplin’s flaws. Beyond pointing out his infuriatingly steadfast perfectionism – even shooting City Lights without a script, causing total production to last around three years – there’s a fair attempt here to examine Chaplin’s problematic relationships with women.

A segment of the film is devoted to exploring Chaplin’s marriages, most of them to teenage girls much younger than himself, and particularly his second wife Lita Grey, who Chaplin married after getting her pregnant underage at just 15 years old. Grey, whose claims of Chaplin’s behaviour have largely been downplayed by the media and society as a whole, are powerfully brought back to the surface here, namely that he was jealous, paranoid, and resented her pregnancy enough to try and pressure her into having an abortion.

As the divorce, the most expensive in Hollywood history at the time, made scandalous headlines worldwide, intellectuals circled their wagons to spring to Chaplin’s defense, labelling Grey an “idiot.” Grey’s claims were never granted the space they deserved in her lifetime, and today offer a fascinating look at how we excuse the extraordinarily talented of allegedly heinous behaviour, as couldn’t feel more relevant in the context of recent social progress.

The filmmakers also flatly call out Chaplin biographers for circumscribing this portion of his life for the benefit of myth-making, while Chaplin himself affords just a few scant lines to Grey in his own autobiography, never mentioning her directly by name.

Though this aspect takes up just a few minutes of the picture, it is an important deviation, even if some may feel that more time could’ve been afforded to those whose stories have been devalued for Chaplin’s benefit. Instead, there’s far more of an interest here in exploring Chaplin’s own victimisation at the hands of the FBI and the press, with the communist witch hunt of the mid-20th century and accompanying personal embarrassments turning the tide of public opinion against him for a time.

Chaplin’s own story attains its most wistful potency, however, as the actor enters middle-age and beyond, where he marries his final wife Oona O’Neill – of who there isn’t a single audio recording, interestingly – and, amid both a career decline and exile from the U.S., settles in Switzerland where he later died in 1977 aged 88.

While fundamentally truncated and imperfect from a narrative perspective, The Real Charlie Chaplin‘s whistle-stop tour approach to its subject is at least abetted by plenty of sleek style. Shrewd editing incorporates myriad primary and secondary sources, both visual and aural, to ensure there’s never a dull moment to be found.

Plugging the gaps of missing footage are reconstructions of the Time magazine interview with Chaplin and an especially poignant testimony from his childhood friend in London, Effie Wisdom. In each case the actors in the recreations are tasked with lip-syncing to the audio recordings, a cutesy flourish yet one that mostly works in situating us in the moment. Tying it all together is quizzical, velvety voiceover narration from Pearl Mackie.

No mere two-hour documentary could do anywhere near full justice to Chaplin’s life – a mini-series could, perhaps – but as a broad primer that reframes his story for modern times (sorry), this is a snappy, stylish work.

Flickering Myth Rating – Film: ★ ★ ★ / Movie: ★ ★ ★ ★

Shaun Munro – Follow me on Twitter for more film rambling.