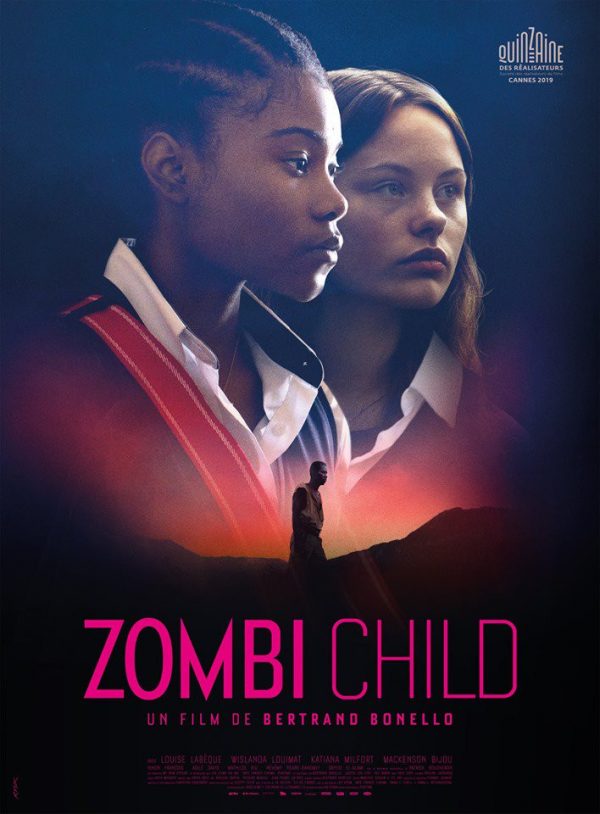

Zombi Child. 2020.

Directed by Bertrand Bonello.

Starring Louise Labeque, Wislanda Louimat, Katiana Milfort, Mackenson Bijou, Adilé David, Ninon François, Mathilde Riu, Ginite Popote, and Néhémy Pierre-Dahomey.

SYNOPSIS:

Haiti, 1962. A man is brought back from the dead to work in the hell of sugar cane plantations. 55 years later, a Haitian teenager tells her friends her family secret – not suspecting that it will push one of them to commit the irreparable.

Horror movie audiences have been trained to recall movies like Child’s Play or Zombie or Hatchet when hearing the term “voodoo.” Vengeful black magic curses, slithery serpent pets, straw dolls stuck with pins and such. Bertrand Bonello’s Zombi Child exists on more hallowed grounds, as Haitian tragedy keys into spiritual enlightenment at the core of voodoo horror. Parallel timelines juxtapose true-to-life “zombi” kidnappings against a modern girl-gang unification, thoughtfully bonded by lineage. The presence of voodoo is meant to educate outsiders about a sacred way of life that eventually leads to the film’s crowning finale. I say “eventually” because outright scares lay dormant for a long while – fear built on hushed rhythms.

We open on Haiti, 1962, where Clairvius Narcisse (Mackenson Bijou) “dies” but is “brought back to life” by men who force him to work on a sugar plantation. Clairvius was merely poisoned and lulled into a comatose state that an antidote awakens, whose new purpose is to work while ingesting more of the numbing powder. This is the life of a “zombi,” robbed of family, freedom, and memories. A sad fate that current-age Haitian descendants like Mélissa (Wislanda Louimat) escape by attending French boarding schools where they meet new friends. In this case, Mélissa is accepted by a sorority of girls who stay up late, gossip, but upon discovering their new sister’s background, one soul foolishly sees voodoo as an answer to her heartbreak.

Zombie Child sheds Hollywoodized accents around voodoo and presents a grounded, experiential way of life. Clouds don’t cascade from the mountains or lightning bolts strike from the sky in prophetic fashion while incantations are uttered. Voodoo is described as “beautiful” and “powerful,” proving the existence of life and death. It’s handled as another classifiable religion versus the fantastical swamp sorcery as so many directors have oversold once upon a time. With a steady calm and ancestral reverence, Mélissa explains to her classmates the ordinariness of voodoo. What it inspires, how it heals, and the cultural impact it has on those with nothing left to believe.

Clairvius’ journey is about the horrors of colonialism, calling back to the I Walked With A Zombie and White Zombie days of early “undead” cinema. The horror afoot is actual slave labor, using nothing but (what looks like) blowfish toxin and some other ingredients. Men snatched from their communities, destined for a lobotomized eternity while others profit. Again, elements of voodoo work themselves in with mundane normalcy – but that doesn’t lessen threat levels. Schoolgirls quip about the grossness of zombies in modern movies like 28 Days Later, but what we see of the real-life “zombi” movement is far scarier than most anything George A. Romero put to screen (film vs. reality a constant theme).

We’re shown two narratives – both about oppression despite their vastly different landscapes. A man who can barely mumble his name and the girl who can’t forget her people’s past. Years apart but forever united by their voodoo influences, which translates to a lecture-heavy first and second act. Quite literally as we digest Mélissa’s French Revolution curriculum; a country’s marred history when shown “forgotten” Haitian legacies. We watch, listen, and learn, but that’s not what every breed of horror fan is programmed to do. I wouldn’t say themes are subtle because they are in-your-face, just more soft-spoken. Sans a few inserts that break the coming of age angle with suggestions that more genre elements are at play than suspected.

Thus brings us to adolescent Fanny (Louise Labeque), who voiceover narrates a string of “love letters” between her and a pen-pal crush as the film unfolds. Young love in its most volatile state, which eventually leads to Mélissa’s aunt (played by Katiana Milfort) showing horror fans what they crave. Katy is a “mambo,” responsible for conjuring an energized third act that brings the thunder of voodoo temptations down upon those who wish to exploit its capabilities (Fanny, without Mélissa’s knowledge). Removing spoilers, just know warnings are ignored and Baron Samedi (brought to life by Néhémy Pierre-Dahomey) – ruler of the cemetery – may or may not make his presence known. Where fantasy and sensibility clash, finally allowing sparks to fly in the form of voodoo gone haywire but still ritualistically rooted.

To its credit, Zombi Child is one of the most authentically in-touch films about voodoo you’ll find (from this non-practicing critic’s perspective). Its uniqueness deserves merit, bolstered by the film’s ability to conjoin two seemingly untethered storylines. Bertrand Bonello could have basely devolved into stereotypes by only focusing on a coven-in-training whose members summon the wrong deity, but that’s a lesser experience. What we’re presented is historically inclined, respectfully taught, and still possession-session-freaky as a final climactic punch. You can’t help but respect a film that knows how to deliver its third act, and if you’re still around when Fanny gets her way, rewards are frenzied and alarming as voodoo terrorization takes centerstage.

Flickering Myth Rating – Film: ★ ★ ★ / Movie: ★ ★ ★

Matt spends his after-work hours posting nonsense on the internet instead of sleeping like a normal human. He seems like a pretty cool guy, but don’t feed him after midnight just to be safe (beers are allowed/encouraged). Follow him on Twitter/Instagram/Letterboxd (@DoNatoBomb).